“Architecture shouldn’t fail itself.”

Teresa Carlesimo voiced these words on a Thursday evening in October 2017 to a room filled with community members, friends, artists, graduate students and curators, during an artist talk with a form of formlessness collaborator, Michael DiRisio. We were gathered together at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, the site of their exhibition, to witness an elaborated presentation on the artist duo’s practice(s). In this moment, Carlesimo was referring to the condominium projects in Toronto—throwaway “luxury rental” buildings designed and erected with such speed and in such great volume, with their inevitable expiry date and environmental footprint defined by their own materiality. Buildings with high-rise concrete skeletons, with glass-walled or cement-covered skin; bodies held deep in forty-foot-plus excavation pits, carved out across the city’s urban fabric. Carlesimo and DiRisio cautioned the room that the condominium towers filling up the Toronto skyline will fail fifteen to twenty-five years after they are built, perhaps even earlier. The short lifespan and energy-sucking characteristics of these buildings are part of their original makeup. And they are, according to Carlesimo and DiRisio, embarrassingly failing themselves.

Artistic and industrial labour converge within the practices of Carlesimo and DiRisio. The two have worked together since 2012 and incorporate common building materials into their mixed-media drawings, sculptural works and photo, video and participatory installations to disrupt familiar understandings of space and value. The social character and political dimensions of the built environment are increasingly central concerns within their individual and collaborative practices. Carlesimo operates within the realm of architectural space, perceptual processes, and viewers’ active relationships to the materiality of constructed forms to uncover the environmental implications of urbanization. DiRisio offers contemplations on collective labour rights as an aesthetic vehicle to counter the capitalist logic of production. In collaboration, their practices bring a visual dimension to their research interests in the ecological and political economy, and labour as a commons. The forms that the artists have produced and gestured toward within a form of formlessness activate this logic of labour and the ways in which our everyday spaces and the world’s current environmental shift are inseparable from capitalism.

a form of formlessness is the artist duo’s biggest departure yet from the representational. The artworks occupy a space defined by their own (re)worked materiality and immateriality. The exhibition’s curator, Sunny Kerr, describes the artists’ exposure of process as an expression of unrest through a kind of base materialism, where Carlesimo and DiRisio “deform and defamiliarize building materials—rubberized rebar, extruded acrylic rod, aluminum studs—and built spaces in an aesthetic taxonomy, searching for new patterns that recognize and destabilize formal habits.”1 Carlesimo and DiRisio’s exhibition poses questions about popular assumptions surrounding space by pushing recognizable potentials of form to its formless limits.

a form of formlessness can be understood as a built environment in its entirety, or even, a series of non-sites;2 an investigation, perhaps, of how we are disciplined by our physical environments through an aesthetic reframing of spatial awareness. The construction of a mirrored infinity room; a video projection of Lake Ontario ebbing and flowing in an (un)natural visual echo against a cutaway false wall; a matte vinyl photograph of an emergency blanket crumpled up into a sparkling alien form—these artworks all exist within a realm of two- and three-dimensionality that is both abstract and representative. The materials’ original object-use remains intact in their physical being, but their existence within a form of formlessness has been shaped into a visual manipulation of the thing(s) that they once were. Through their quasi-minimalist constructs, the artists have provided a bare envelope of formlessness—a series of reconfigured materials that negate the primacy of perception, as they point away from themselves and back to their original industrial material forms.

In terms of form found within visual art more generally, the analytical anthology of anti-art and meta-art website, “radical art,” attests that, “Art is concerned with form. (Visual shape is a metaphor for conceptual form). But in the course of the twentieth century, this very notion (form) has become suspect. This situation creates an interesting challenge for the visual arts: to find a form for formlessness, to show the form that has no form.”3 To this end, my textual response to a form of formlessness as follows is an experimentation in form itself, and takes a note from Rosalind E. Krauss and Yve-Alain Bois’s Formless: A User’s Guide.4 Through various acts of material research, I’ve grouped together a series of disparate thoughts into one self-contained written work, in an attempt to embrace formlessness and inquire into its generative possibilities.

_____

cement and concrete

Last winter I found myself wandering through the ruins of a cement factory in Marlbank, Ontario—a small community located in Tweed, a few kilometres west of Highway 41. Recognized as one of Southern Ontario’s “ghost towns,” Marlbank is nestled among farmland and forest, its present-day appeal mostly assumed by cottagers with summer homes along Lime Lake, White Lake and Dry Lake. Arguably, the town’s main attraction is the standing remains of the Marlbank Canada Cement Company.5 Walking between kilns that once processed the cement, an eerie calm takes hold. The material’s own production site—the factory and the land on which it is situated—is now in peril.

The soil in the Marlbank area was once considered ideal for making cement. Marl, after which Marlbank is named, is a grey, clay-like substance that was a valued mineral deposit used for cement manufacturing in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In 1907 alone, thirteen plants in Southern Ontario—Marlbank’s cement factory, included—produced Portland cement from marl, and interest continued long after its use was superseded by limestone quarrying.6 At its height, the cement plant employed two hundred people. After the plant closed in 1914, the population of Marlbank dropped from one thousand to just a couple of hundred. The train tracks were taken out in 1941. They say that marl is good for the skin—if you go to Dry Lake, just east of the old factory, you can swim on marl beaches.

Cement manufacturing, like many other manufacturing processes for building materials, begins at the mine. The raw materials—limestone, silica, aluminates, ferric minerals and others alike—are extracted from the earth’s hold. The production of one tonne of cement directly generates 0.55 tonnes of carbon dioxide and requires the combustion of carbon-fuel to yield an additional 0.40 tonnes of carbon dioxide. Essentially, 1 tonne of cement = 1 tonne of carbon dioxide.7 This underrated polluter has extremely detrimental impacts on the environment and carbon economy. A direct trade-off between development and sustainability is at play with cement’s high production: “So as demand for cement grows, for sewers, schools and hospitals as well as for luxury hotels and car parks, so will greenhouse gas emissions.”8 Cement, aside from water, is the main ingredient required to produce concrete.

From skyscrapers to Toronto condominiums, patios to bridges, house foundations to office buildings, concrete is key to countless architectural structures simply because it is a good building material. In its simplest form, concrete is a mixture of paste and aggregates. The paste, composed of Portland cement and water, coats the surface of the fine and coarse aggregates. Through a chemical reaction of hydration, the paste hardens and gains strength to form the rock-like mass known as concrete. It is the world’s single most widely used material. And now in its hipster height, concrete’s fame on Pinterest and DIY blogs generates articles daily that boast:

10 Surprisingly Creative Uses of Concrete Blocks in Your Home and Garden!

17 Unexpected Ways to Decorate with Concrete!

How to Easily Make Your Own Minimalist Concrete Décor!

And I have to admit…the DIY concrete coffee table did catch my eye…However, camouflaged behind its popularity as a modern day minimalist decor material, what has become increasingly clear with concrete’s expanding production (but remains shielded from popular knowledge), is its environmental impact. Concrete’s carbon footprint matches its wide use: the concrete industry is one of two largest producers of carbon dioxide, creating up to five percent of worldwide human-created emissions of this gas.9 Concrete is responsible for so much carbon dioxide output because its key ingredient, cement, requires such significant amounts of energy to reach reaction temperatures, and also because “the key reaction itself is the breakdown of calcium carbonate into calcium oxide and CO2.”10 Beyond that, concrete production has immeasurable impacts on landscape degradation, dust and noise pollution, and water withdrawal and consumption. Not to mention the fact that the resources required for industrial production are being uprooted and extracted from Indigenous land.

_____

aluminum

In her documenta 14 essay, “The Gilded Gaze: Wealth and Economies on the Colonial Frontier,” curator Candice Hopkins focuses on the extractive colonial pursuits of the Klondike Gold Rush. She defines the attachment of value that comes with mining and manufacturing processes as one that requires consensus determined by capitalist greed, desire and the scarcity of things considered “relatively rare.”11 As Hopkins contends, in terms of the Klondike in the 1800s, “gold was the mediator between the West and the East, between Indigenous and colonial, between a local commodity and distant markets. It was via the metal that the miners initiated new economic and social forces, ones that entirely usurped local economics, ideologies, and forms of justice.”12 These defining characteristics of value—steeped in colonial-capitalism—can undoubtedly be applied to a plethora of metals, not simply gold. In fact, in the mid-1800s, aluminum was considered more rare and valuable than gold.

This wonder metal’s sense of value can be attributed to two qualities: its adaptable materiality and its symbolic meaning. Aluminum remains the “metal of the future,” wrapped up in its culturally historical associations with concepts of modernity, innovation and progress. From 1910, when the first aluminum foil rolling plant was founded, to the 1960s, aluminum production amassed to an industrial scale like no other, unlocking a material culture aligned with an entire world of capitalist spectacle and new modern attitudes. The electrochemical smelting of aluminum brought with it new heights of speed, architectures of luminosity, and the conquest of air and outer space. Aluminum and its alloys have made their way into just about everything: transportation, electrical, military-grade hardware, construction, aeronautics, and ship-building industries; as well as in domestic design, architecture, technical equipment, and various banal products of everyday life. It fundamentally changed the game of the built environment, the mobility of the human body, electricity and other extracted resources. As production soared, prices plummeted. The first aluminum ingots on the market went for $550 per pound. At the beginning of the twentieth century, inflation aside, the same amount of aluminum cost consumers twenty-five cents.

While aluminum today has lost much of its early high-tech lustre, in part through its association with mundane objects13 (such as artificial Christmas trees, beer cans, and dollar store cookware), its materiality and meaning continue to shape our current historical moment. Although no longer considered precious or rare by any means, aluminum has maintained its momentum and enthusiasm alongside its contributions to modernity, transnational capitalism, militarism and extractive colonialism.

Aluminum is the world’s most abundant metallic element,14 but it does not occur in a natural state. Producing aluminum is costly, laboriously difficult, and beyond that, environmentally detrimental. The most available source of aluminum is bauxite ore, which is processed into alumina before becoming primary aluminum metal. Today, the majority of aluminum’s hydroelectric plants and mines (that exist within, displace, and ecologically destroy land and waterways) can be found in Australia, China, Brazil, India, Guinea and Jamaica. The world’s largest producers of aluminum are China, Russia, the United States and Canada. Bauxite mining is an open pit process that leads to deforestation and leaves behind toxic “red mud” lakes that can overflow and pollute local groundwater. After mining, comes aluminum smelting, which is one of the most energy-intensive production processes on earth:

Out of the pots, presses, and rollers,

a tidal wave of castings,

forgings,

and sheets of metal

enter the factories of the world

to be turned into finished goods

such as car parts and airplane fuselages,

cans and wrappers,

kitchenware and foil,

chairs and satellites.15

A multitude of undeniable connections exist between resource extraction industries and colonialism, past and present. Mining operations consume large sections of ancestral Indigenous land, commonly without community knowledge or consultation, and rarely with alternatives being offered. The long-term, often-irreversible effects of extraction activities are not only limited to environmental degradation, but also include increases in substance misuse, violence against (mostly Indigenous) women, and continuously precarious working conditions via the economic pattern of “cyclonics”—whereby extraction projects bring jobs, money, materials, resources and skills into remote areas in a whirlwind and leave just as quickly once the resource is exhausted.16

This process of colonial-capitalism, through the pursuit of resource capital by means of industrial encroachment onto Indigenous land, is described by social science scholars Kelly Rose Pflug-Back and Ena?emaehkiw Kes?qnaeh as “accumulation by dispossession.”17 Pflug-Back and Kes?qnaeh have written on the value that becomes placed upon raw materials, metals and minerals, once deemed necessary for industrial manufacturing processes, and the cost that comes with this value:

Maehkaenah-Menaehsaeh (Turtle Island) has sustained people and other living things from time immemorial. Complex and interconnected systems of life make up its forests, rivers, lakes, prairies, and tundra. Beneath the ground, millions of years of intricate geological processes have resulted in deposits of copper, oil, and other metals and minerals, which Indigenous peoples have used for generations. In the eyes of the European colonists who began occupation in the 1400s, this land held a different kind of value. Ancient forests could be logged, and the timber sold or used to build ships, railroads, and settlements that would nourish population growth and stimulate the economies of their home countries through remittances. Copper, gold, coal, and other metals and minerals could be ripped from the Earth using industrial technologies that had irreversible effects on the environment.18

The often-hidden environmental degradation impacts, cyclonics and capitalist-colonial processes of resource extraction and mining become effectively shielded through mass-produced, monotonous forms.19 With everyday associations of material commodities produced from cement, concrete, aluminum, and others alike, comes a sense of mundaneness and non-rarity. Perhaps by pausing, reconfiguring and deforming, the mundane camouflage can be pulled back, and the raw materials and their associated formations of value can be brought into focused perspective. I would argue that this is the artists’ emphasis within a form of formlessness—whereby formlessness is used as a method to strip away materials’ familiarity that otherwise allows them to maintain mundane anonymity and exist as unremarkable, and therefore, inaccurately labelled as non-threatening.

_____

“If you want people to engage with art, put a mirror in it.”20

Their ideas about the structure are not the same as the structure itself; but only part of the negotiation between their shared practice(s). His mind is on the media player and the projector’s throw. Hers is on the false wall. She has Home Depot’s standardized measurements memorized down to a science. Building a mirrored infinity room within an art gallery causes the foreground and background to blur into a flurry of (mis)recognitions. Carrying this method forward throughout the entire exhibition—a collaborative effort, yes, but all the while with their individual practices at play, overlapping and speaking to one another—the artists invite viewers into a social reading of their constructed forms. The mirrored infinity room, echoing the exhibition’s title as a form of formlessness, calls visitors into its interior through a vibrating and buzzing reddish-pink glow that bounces off the gallery walls. (Fig 1) The constructed space can be entered through a tasseled curtain cut from a sheet of shiny, and almost sticky, metallic foil. The room was specifically constructed by the artists for this project and it will no longer exist post-exhibition; its lifespan has been determined by the exhibition’s run.

Their mirrored world, with shifting, clouded skies projected above, destabilizes visitors’ encounters in a quirky and endlessly repeated ultra-glam aesthetic. (Fig 2) And all I wanna do is dance. The gaps between the mirrored panels offer an added moment of disjointed reflection; a reflection that does not offer a fully realistic rendering, but further multiplies and alters one’s own and others’ bodies. The dislocation and discomfort of the mirrored faces staring back at you, mixed into a flurried sense of play, with the swirling sky above, moving in and out of sorts with corporal reality, nonetheless make visitors hyper-aware of the structure within which they are enclosed. How can the built environment act as a vehicle of research? What can we learn from its own instability, as determined by its materials and their planned obsolescence?

The mirrored room’s meticulous construction is left undone by the exterior’s exposed insulation panels. A sexy industrial glow from the fluorescent bulbs bounces off the ultra-luminous panels and its moulded expanded polystyrene. The mirrors are sourced from a Kingston-based glass production company, the cloud video from open-access YouTube content.21 The room’s materials and overall structure offer a reading that plays into the myth of constant expansion. Contradictory notions of infinite expansion within a finite space are brought into direct conversation through the mirrored room’s own materiality and built form. All at once the installation references mining, resource extraction, the potentials of building materials and their environmental limitations. As Kerr contends, Carlesimo and DiRisio have produced “a 21st-century reckoning: to weigh the compulsions of development on a finite planet.”22 a form of formlessness actively refutes the lingering public argument that economic growth is the natural solution to virtually all social problems: poverty, debt, unemployment and even the environmental degradation caused by the determined pursuit of growth. The exhibition pokes fun at the neoliberal notion of endless growth of resources, and brings into focused realization the inability to sustain our planet’s current level of industrial production—the cost is just too high.

_____

assemblage assembly

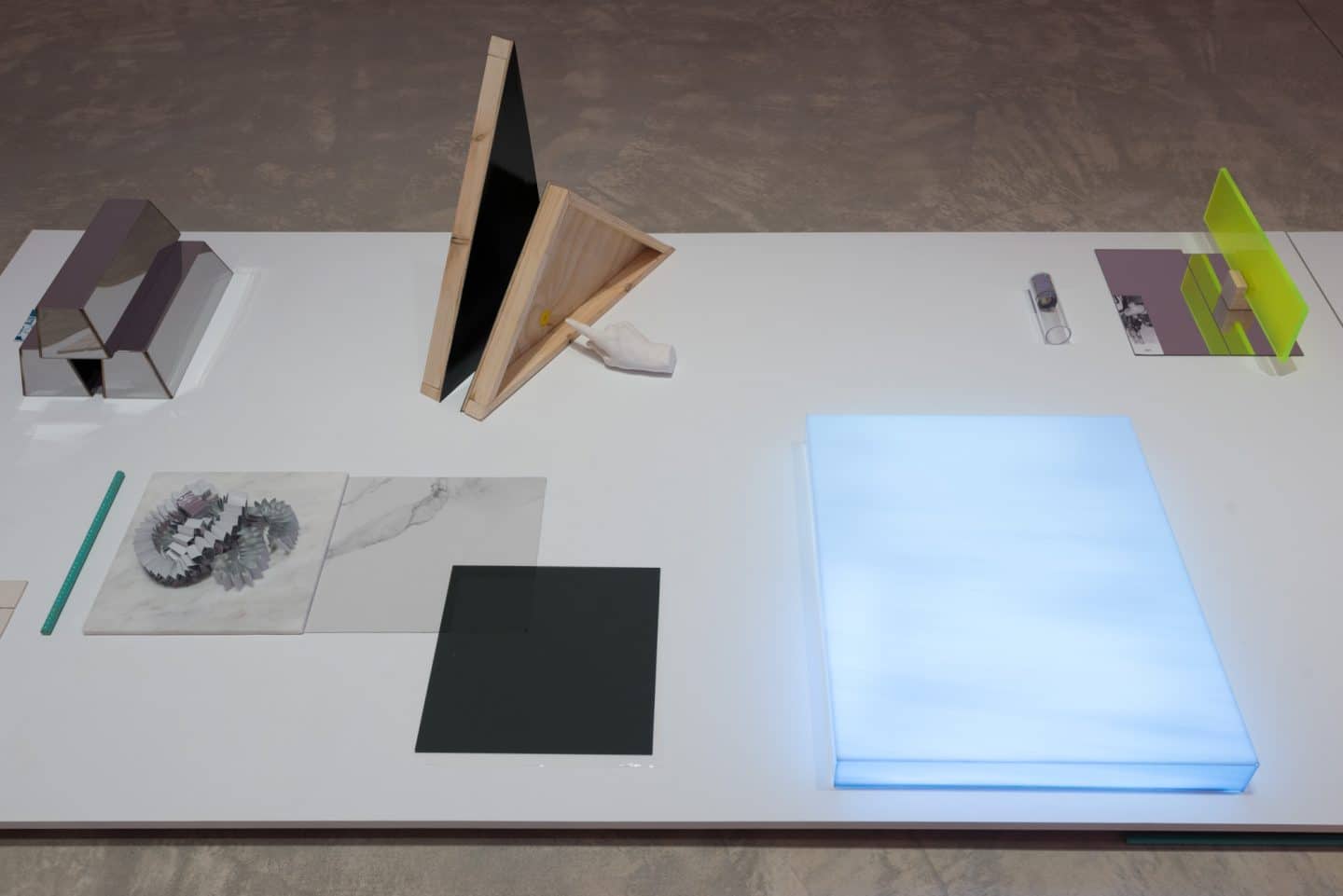

| Carlesimo/DiRisio | a form of assembly | Aluminum drip edge w/ oak stand |

| Carlesimo/DiRisio | a form of assembly | Extruded acrylic rod |

| Carlesimo/DiRisio | a form of assembly | Extruded acrylic cylinder |

| Carlesimo/DiRisio | a form of assembly | Reflective insulation |

| Carlesimo/DiRisio | a form of assembly | Acrylic lightbox w/ LED and vinyl digital print |

| Carlesimo/DiRisio | a form of assembly | Digital photo print w/ found steel |

| Carlesimo/DiRisio | a form of assembly | Plaster cast |

| Carlesimo/DiRisio | a form of assembly | Fluorescent-cast acrylic |

| Carlesimo/DiRisio | a form of assembly | Chromed steel mud pans |

| Carlesimo/DiRisio | a form of assembly | Emergency blanket |

| Carlesimo/DiRisio | a form of assembly | Pine dimensional lumber and 1/4" plywood w/ rubberized rebar |

| Carlesimo/DiRisio | a form of assembly | Fruit wood, plaster and paint |

| Carlesimo/DiRisio | a form of assembly | Ceramic tile, natural rubber ring, window blind off-cut |

| Carlesimo/DiRisio | a form of assembly | PCV pipe, natural rubber |

| Carlesimo/DiRisio | a form of assembly | Reflective bird deterrent tape |

A playful nod is apparent within a form of assembly—in its elongated plinth and detailed list of component parts23—to the tradition of assemblage. Popularized during the 1950s and 1960s, assemblage is a form of visual art that consists of three-dimensional co-functioning materials defined as “wholes.” An assemblage entertains temporary and provisional connective arrangements whose elements are usually drawn from everyday items that may otherwise be unrelated and considerably mundane. An assemblage approach prioritizes relations of connection as defined by the grouped interactions that take place between materials, but still leaves space for each to maintain their casual autonomy, to some degree. The beauty of assemblages is that they are never complete nor stable in their construction; they always leave room for rethinking systems, potential interactions of failure, and other possibilities in rearrangement. A pattern of relations can be assumed through the list of objects submitted by the artists for a form of assembly: the individual items appear to be connected to each other by their industrial origins (or even just how much they invoke a postmodern 1980s/90s glam retro wonderland).

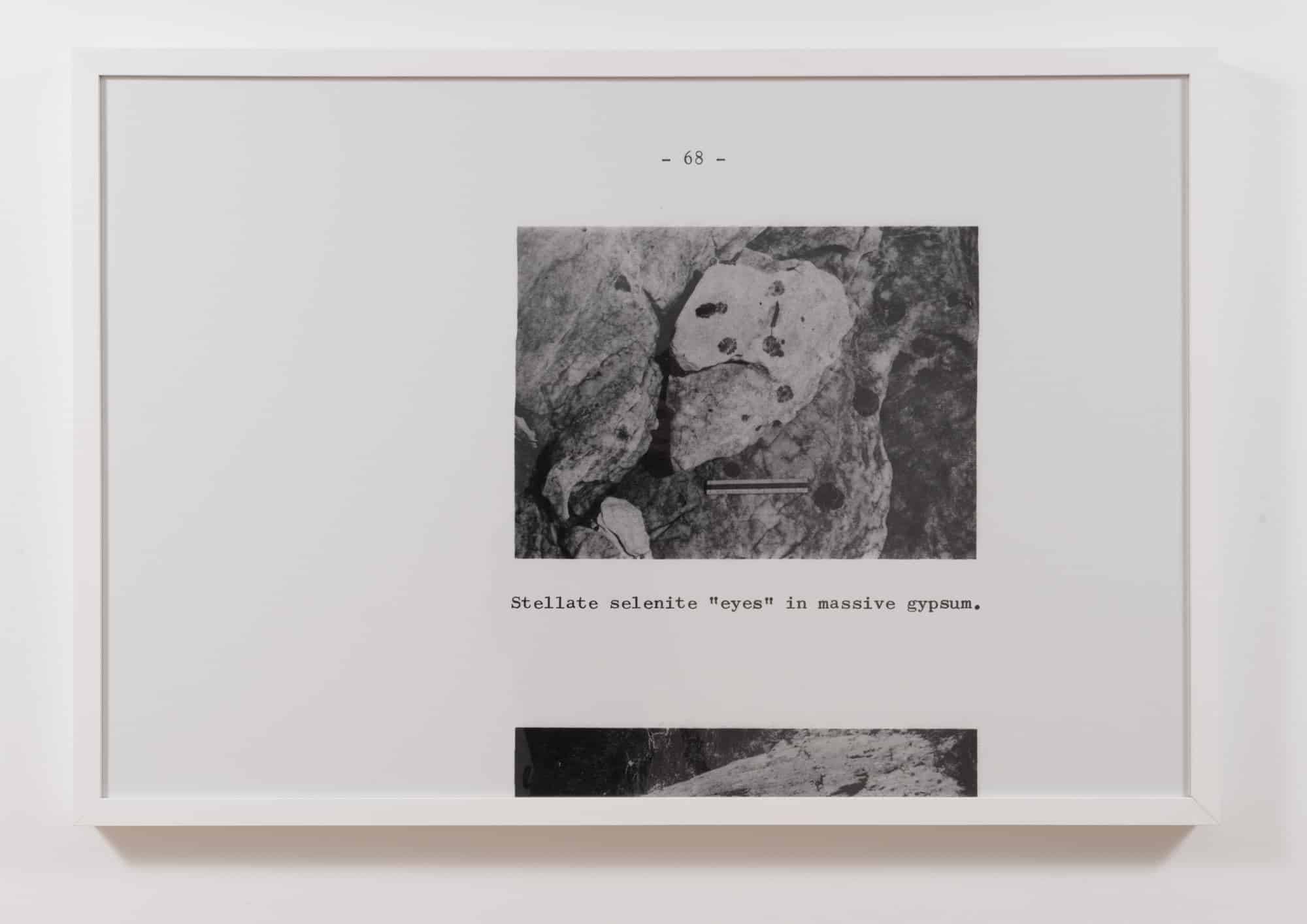

Nuanced questions get left out in the open with a form of assembly’s intentionally withheld context. What are the relationships we are meant to witness in this work? Why is there an LED lightbox with chromed steel mud pans? What is a ceramic tile doing with reflective bird deterrent tape? The “inside scoop” from the artists reveals that these are all objects of exhibition refuse, things that didn’t quite make their way onto the walls: samples of different mirrored material from hardware supply stores in Kingston; a leftover wall cleat with pencil-marked measurements from the construction of the mirrored infinity room; an archival image of Local No. 1005 members deciding to strike the Steel Company of Canada (Fig 5); a blue light bulb used to photograph a form of unrest II. Laid out and arranged in an almost scientific assemblage of spare parts, a form of assembly can be considered an act of exposing material research within the exhibition. These refuse materials were not selected at random, but rather they uncover their own direct environmental impact. The emergency blanket is not just a pretty swirling and shiny shapeless form on a whirring motor; it also references the mass industrialization of aluminum-based products by which we build up our lives, reinforce our survival, and engineer our architecture.

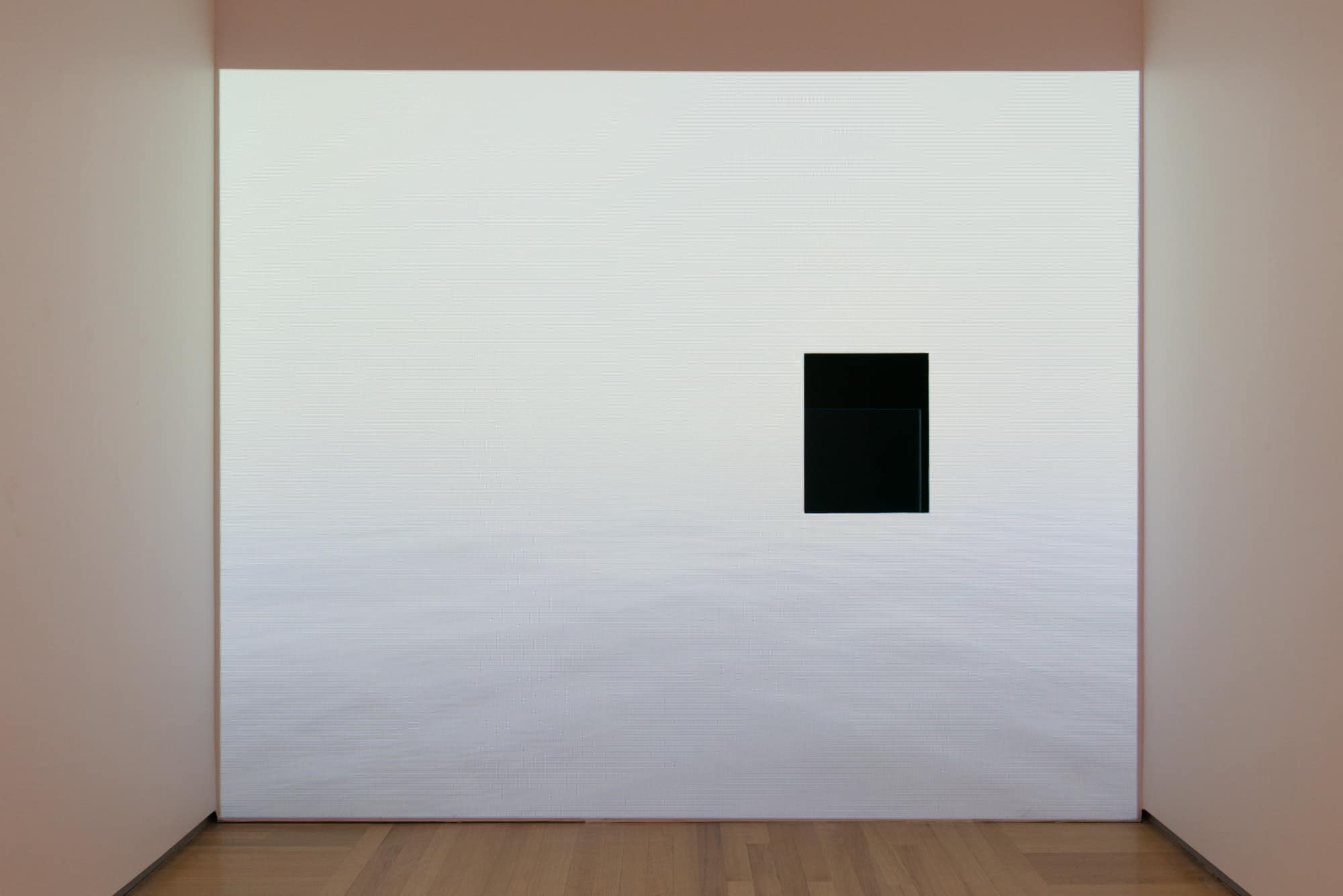

The artists’ single-channel video of a peaceful view of Lake Ontario acts as an anchor to a form of formlessness. Visitors apprehensively and cautiously stick their heads and hands through the black rectangle that cuts through the projection’s image. It’s unclear at first whether the rectangle is truly extracted space, or simply part of the video. In reality, the projection is being cast onto a false wall that has been cut away and modified to reveal a rupture, in a Gordon Matta-Clark anarchitecture fashion. The space is all at once empty, yet filled by the projector’s black light. This act of partial destruction through cut removal allows the wall to become repurposed and live in another state of being: a referenced form as a light box with the lake’s rippled pattern overlaid, placed on display with its modern contemporaries of extracted materials as a form of assembly. In this sense, the false wall participates in its own type of oscillation or exchange with the “something else” of the work, by its repurposed use. Its obsolescence has been planned in its construction, essentially echoing the architectural patterns of Toronto condominiums. Cutting out a wall behind a moving image of water also serves as a reminder about just how much water is needed to produce said materials. Considered to be the most valuable resource, water cannot be removed from the conversation of industrial production and value.24

_____

“There needs to be space for the glow.”25

With the non-site model of the exhibition—wherein its building materials are signifiers, and the alluded-to site is that which is signified—a space of abstraction is effectively created. Considering the space needed for light, or “the glow,” viewers are encouraged to think of the immaterial, of the impalpable, of the “something else.” For artist Eva Hesse—unlike her minimalist contemporaries of the 1960s, whose reductionist reasons often had to do with being true to the medium or materials—reduction was motivated by a deliberate decision to create a space of absence. Are we being called to witness such a space within a form of formlessness?

During Carlesimo and DiRisio’s artist talk, a time-lapse video bookmarked the conversation. Scenes documenting the installation period of a form of formlessness played in a flurry behind the artists, providing visual proof of the invisibilized and forgotten preparatory labour involved in exhibition-making. Within their own individual and collaborative practices, Carlesimo and DiRisio are very much invested in the politics of artistic labour and often utilize this form of documentation to bring these behind-the-scene moments into direct dialogue with the final exhibition product—the site of production and the site of exhibition effectively merge into one. The gallery is a work site, after all. At times within the video, an eruption of movement activates the scene, bodies in motion through a surveilled performance of labour—painting, cutting, building, rearranging, installing. At others, the room is still. There is rest. Necessary rest. We are invited as an audience to literally witness their work, as both product and process, and acknowledge the often-absent recognition of both human labour behind an exhibition, and the environmental impact behind each and every mundane material we encounter in our daily physical environments.

_____

Endnotes

_____

Works

Mixed media

Mixed media

Vinyl printed digital image

Paint chips on paper/Digital C-print

Mixed media

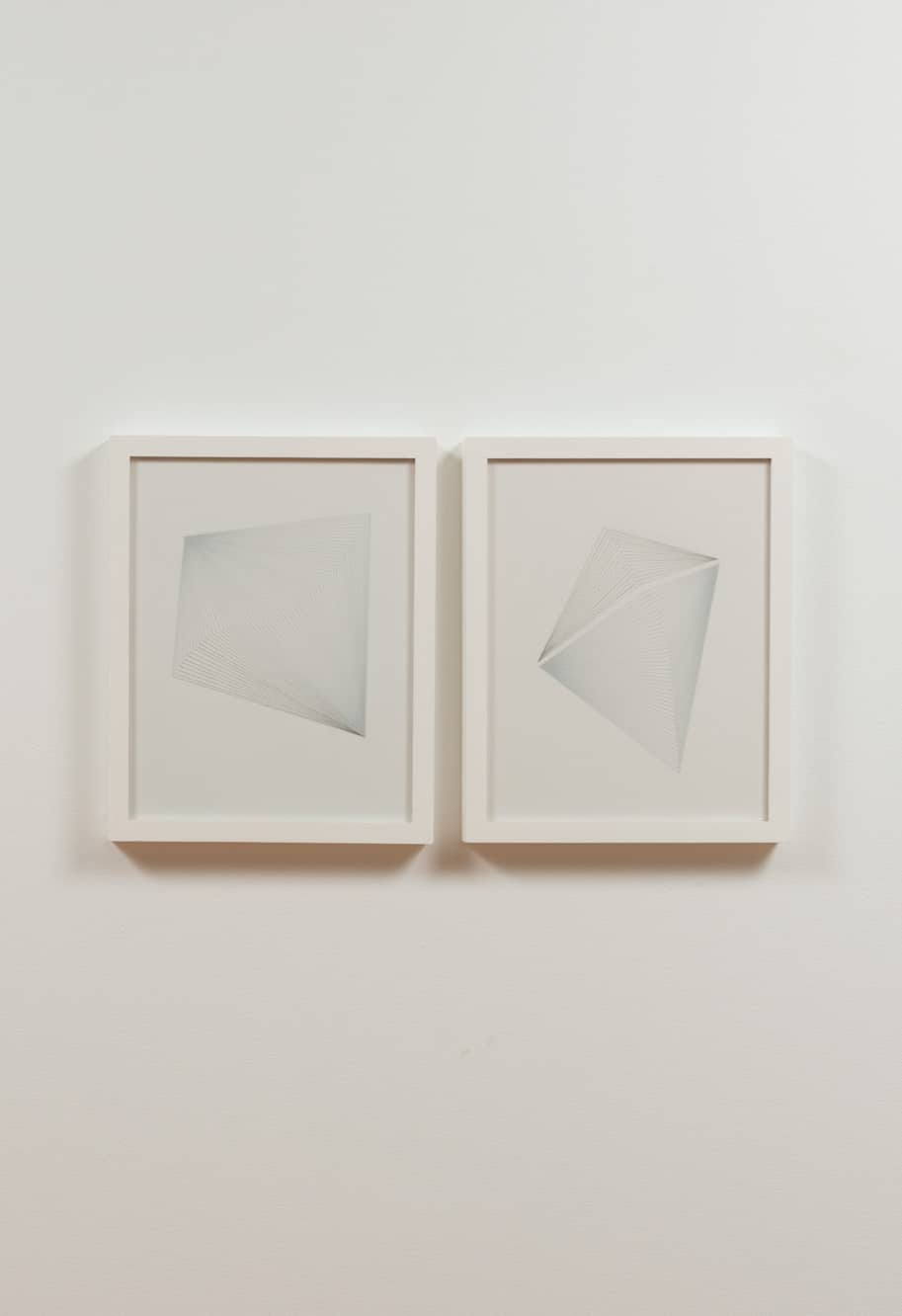

Ink on paper, graphite on polypropylene

Aluminum foil, drywall and acrylic paint

C-print

Single channel video, projected, with wall modification

Biographies

_____

Acknowledgements & Credits

This publication documents the exhibition a form of formlessness presented at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen’s University, Kingston.

a form of formlessness

26 August–3 December 2017

Agnes Etherington Art Centre

36 University Avenue

Kingston, Ontario

Canada K7L 3N6

Curator: Sunny Kerr

Author: Carina Magazzeni

Copy Editor: Shannon Anderson

Photography: Paul Litherland

Design: Kelsey Blackwell

© Agnes Etherington Art Centre 2018

ISBN: 978-1-55339-622-2

This exhibition and its associated programs and publication are supported by the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council (an agency of the Government of Ontario), the City of Kingston and the Kingston Arts Council through the City of Kingston Arts Fund.