Nueva Esperanza workshop, Untitled, mid-1980s–early 1990s, applique, embroidery and crochet on fabric. Courtesy of the Jubilee Crafts collection currently hosted by SUNY Potsdam’s Gibson Gallery

•

In Spanish, the phrase hilos conductores can mean two things: conductive threads and the main idea or theme of a story.

1. Copper is one of the best electrical conductors of all metals. Chile is the biggest exporter of copper in the world, supplying 28 percent of this essential resource to global markets.1 On the other side of the hemisphere, the corporate landscape of downtown Toronto—where Sur Gallery is located—is dotted with the headquarters of mining companies that operate in Canada, Chile, and beyond.

2. Extractive industries like mining require large volumes of water for processes that often lead to water scarcity and pollution. This is especially pernicious in countries like Chile, where water is privatized and thus exploited for profit. The Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan owns over 34 percent of water rights in the South American country.2

3. Electric shocks and electrocution are used by repressive regimes as punishment. During the Chilean dictatorship (1973–1990), parrillas (electrically charged beds) were used to torture dissidents. These acts of violence created the necessary conditions to roll out an economic agenda based on the extraction and export of natural resources.

4. During the Chilean dictatorship, arpillera makers used threads and scraps of fabric to tell their stories of loss, struggle, and resistance. Today, artists and textile collectives continue to draw on this tradition of creative resistance to foster memory, denounce injustices, and instigate social change.

Pulling on these hilos conductores, this exhibition brings together arpilleras created during the Chilean dictatorship and recent works by textile artists and collectives to follow the threads linking our lives and futures together. While grounded in personal histories and local resistance, the textile pieces presented by Bélgica Castro, Soledad Muñoz, Tamara Marcos, Memorarte, and Autorretazo respond to accumulation schemes and supply chains that entangle distant geographies. By presenting these works together with arpilleras created between the 1980s and the early 1990s, this exhibition honours the work of arpillera makers and the longstanding struggles against authoritarianism, free-market economics, and extractivism that continue with such urgency.

Exhibition Rationale

The social revolts (2019–2020) and recent efforts to write a new constitution in Chile re-energized leftist and radical imaginaries around the world under the premise that, just as Chile was the cradle of neoliberalism, it could also be its grave. However, as a resource-rich country with a development strategy predicated on foreign investments and exports, the landscape of possibilities pried open in Chile by these processes are enmeshed within the global demand for raw materials and investment schemes plotted in boardrooms that are often located far away. But while the mining industry and other interest groups have closely monitored the potential reverberations that social unrest and a new constitution might pose with regard to their market performance and prospects, a lot remains to be examined from a critical perspective.

Attending to these gaps, Hilos Conductores brings together art and extractivism to uncover the complex global dynamics that connect distant geographies and to explore the role that political textiles3 might play as we try to unravel them. This exhibition is also an invitation to reimagine transnational and human–nature relationships beyond those dictated by the global economy.

The research and relationships behind this exhibition come from my doctoral project in Human Geography at Queen’s University, Kingston. This research was mainly conducted during the Chilean revolts in Santiago and was impacted by the coronavirus pandemic. While unable to provide a complete overview of arpilleras created during the dictatorship and the contemporary practices that are grounded in this tradition of textile resistance, Hilos Conductores is an interdisciplinary project that engages a broader Canadian audience through artworks that are unexpectedly connected to our lives.

This untitled arpillera is signed by the Taller Nueva Esperanza (New Hope Workshop, mid-1980s–early 1990s). It is part of the Jubilee Crafts collection. The scene depicted in this textile is a self-representation of an arpillera workshop, where women gather to work on their arpillera projects.

Arpillera (ar-pee-air-ah)

In Spanish, the word arpillera refers to a burlap textile. In addition to its many applications, this material is used in craft and artistic practices such as lanigrafía, or wool embroidery over burlap. In Latin America this technique is widely known thanks to the work of Chilean songwriter and folklorist Violeta Parra, whose arpilleras were exhibited at the Louvre (Paris, France) in 1964. Parra was the first artist from the region to present a solo show in the museum.

Drawing on these cultural and material traditions, victims of state violence, relatives of the detenidos-desaparecidos (detained-disappeared), and women from poor and working-class neighbourhoods created arpilleras during the Chilean dictatorship. These are often referred to as arpilleras de la memoria (memory arpilleras), or arpilleras históricas (historical arpilleras). During this period, arpilleras were mostly created in workshops coordinated by the Vicaría de la Solidaridad (Vicariate of Solidarity), a human rights branch of the Catholic Church that provided legal and economic aid to victims of state violence.4 In these workshops, arpillera makers employed patchwork and embroidery techniques over potato and flour sacks, using fabric scraps, yarn, and other materials from everyday life to chronicle their experiences of loss, economic precarity, resistance, and hope.

Besides the extraordinary contributions that arpillera makers have made to artistic expression and practices of collective memory and resistance, the very materiality and techniques employed in their creation stands out. Within the modern Western imaginary, textiles and embroidery are inseparable from questions of gender,5 and the dichotomy between arts and crafts.6 The politics mobilized by arpilleras trouble these assumptions, and highlight the power of textile artists to intervene in geopolitical and economic conversations through unexpected mediums.

The dictatorial arpilleras selected for Hilos Conductores come from the Jubilee Crafts collection via SUNY Potsdam, New York. While not all of the arpilleras are signed, some are attributed to individual arpillera makers or workshops. These include Silvia Pardo, Celia Armijo, Soledad Moyanoll and Juana D. from Taller Santa Elvira, Ester from Taller Santa Adriana, Taller Mujeres, La Nueva Esperanza, Taller Los Amigos, La Araucaria Taller, Taller La Faena, and an unidentified workshop in Puente Alto.

Jubilee Crafts was a women’s collective that sold fair trade international crafts between the 1970s and 1990s in Germantown, a working-class neighbourhood in Philadelphia. Among other items, the collective sold and exhibited hundreds of arpilleras to support economically vulnerable populations and to educate people about US foreign policy toward Chile. Decades after Jubilee Crafts closed its doors and Chile returned to being an electoral democracy, this arpillera collection ended up in the North Country region of New York thanks to M.J. Heisey, a member of the collective and a history professor who joined her colleagues at SUNY Postdam and St. Lawrence University in 2019 through the Forging Memory project. As part of this project dedicated to studying the collection and exhibiting it, the Forging Memory team interviewed arpillera makers María Madariaga, Patricia Hildago, Victoria Diaz, Emilia Vasquez Requelme, Laura Herrera, Carmen Aravena Indo, Aida Moreno, and Sylvia Avancado.7

The Jubilee Crafts collection is currently under the care of Chilean professor Liliana Trevizán, who will return the arpilleras to Chile as a donation to the Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos in Santiago.

The Circulation of Arpilleras

Given the general environment of repression and censorship that prevailed in Chile throughout the dictatorship, arpilleras were mostly circulated, sold, and exhibited abroad by Church-related groups, Chilean exiles, women’s collectives, and leftist organizations. To get there, arpilleras were often smuggled outside of the country, shipped as fair trade merchandise, or transported by individuals acquainted with the Vicaría de la Solidaridad (Vicariate of Solidarity, 1973–1992).8

On a few occasions, packages of arpilleras were intercepted by customs or reported by Pinochet’s sympathizers living abroad. These discoveries were reported on by right-wing media inside of the country, which tried to undermine the textiles as “naive” while simultaneously portraying them as anti-Chilean and Marxist propaganda, two serious offences at the time.9 These media representations are revealing, as they demonstrate the military junta’s concerns regarding Chile’s image within the international community. The arpilleras depicted hungry children, social unrest, and police violence at a time when Chile’s dictatorial regime was trying to position the nation as a favourable market for foreign investment; a place where living standards had improved and political unrest had been tamed. Arpilleras—with their so-called “naive” subversiveness, travelling widely throughout the world—hampered these efforts.

The Economic Legacy of the Dictatorship

The 1973 coup d’état against Salvador Allende not only put an abrupt end to the socialist project advanced by his Unidad Popular (UP) government, but it also created the conditions to restructure Chilean society under the banner of a free market economic system that we know now as neoliberalism. This economic model is characterized by a series of policies that foment trade liberalization, the restructuring of the state to facilitate market efficiency and the privatization of key services like pensions, health care, and education.10 Given that Chilean soils are rich in metals and minerals, the neoliberal doctrine dictated a development path based on extractive industries like mining and exports.11

In 1980, Pinochet’s regime instituted a new constitution to legally enshrine this economic model and ensure its continuity beyond the end of his mandate. Thus, while the return to electoral democracy in 1990 is not insignificant, post-dictatorial governments have been unable or unwilling to transform the economic model that they inherited. The entrenchment of the neoliberal system in the post-dictatorial period has carved out an important role for Chile within the global economy, particularly when it comes to the export of key natural resources such as copper and lithium.12

While this economic strategy has resulted in episodic macro-economic booms and created huge profits for private investors, the lack of redistributive policies means that this model has not benefited the broader population. In fact, 53 percent of Chilean households are financially vulnerable13 and the country has one of the highest indexes of inequality among the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.14

Extractivism and the Transnational Landscapes of Mining

In its most basic expression, extractivism refers to the removal of natural resources, such as petroleum, metals, and lumber, with the goal of supplying raw materials for global markets via exports.15 At this stage, extracted materials undergo very little if any processing, meaning that the social and ecological costs of extractive industries don’t translate into high value-added benefits to the communities and ecological systems sacrificed for this processes.16

The procurement of basic resources through extractivism is central to the reproduction of the global economy. Therefore, access to resource wealthy regions has historically been at the centre of much colonial violence, foreign interventions, and economic restructuring programs (as in SAPs). The geographies of extractivism are informed by processes of racialization and hierarchization that justify the sacrifice of peoples and territories—along with the ecological and belief systems that are inseparable from them—to ensure the conditions of existence and domination of a global minority and the functioning of the system that supports it.17

Academia and art institutions have contributed to the appropriation and dismissal of visual and expressive practices that do not align with Western modernity and its scientific and economic rationales. They have also perpetuated the exoticization of colonized landscapes for consumption.18 As such, art is not simply illustrative of the trickledown effects of extractivism, but is deeply imbricated within the geopolitics that have historically shaped it.

Soledad Muñoz, whose work is featured in this exhibition, has noted the connections between Chilean extractive industries like mining, the academic practices that brought neoliberal economics to her country via the work of the Chicago Boys, and the extractive ways in which some academics and art collectors have appropriated arpilleras for self-promotion.19 While she recognizes the strategic importance of protecting the anonymity of arpillera makers within the context of the Chilean dictatorship’s repression, Muñoz calls for the restitution of their authorship and voices whenever possible, as well as the need to write about them from “a deconstructive anti-capitalist approach.”

La parte de atrás de la arpillera (The Back of the Arpillera, 2020) is an audio-visual arpillera20 that documents the living contributions of arpillera makers in their own words. With footage from interviews and the 2019 social revolts, this documentary shows how generations of arpillera makers have been at the centre of anti-dictatorial and anti-neoliberal resistance.

Canada and Chile: Uneasy Relations

Canada is a major yet often inconspicuous player in this story. Ottawa recognized Pinochet’s military government within weeks of the coup and, while other embassies moved to grant diplomatic asylum to people fleeing Chile, the Canadian embassy was initially reluctant to allow people in.21 Informed by strong Cold War sentiments and national security rhetoric, this attitude translated into lengthy screening processes that vetted people with strong ties to communist and Marxist ideologies in favour of individuals that could presumably better adapt to life in Canada.22 While these asylum seekers waited, opponents of the regime in Chile were raided, detained, tortured, killed, and disappeared.

Canada ended up admitting approximately 7,000 refugees thanks to the pressure of political and civil society groups, including opposition parties and Canadian churches.23 Their actions contributed to the creation of a special class for refugees within the 1976 Immigration Act, forging a new era for Canada as a refugee receiving country. Exile is another hilo conductor tying the fate of distant geographies.

While this humanitarian crisis unfolded, “the Canadian government was negotiating trade and debt-reduction agreements with Pinochet.”24 These negotiations set the ground for the landmark Canada–Chile Free Trade Agreement (CCFTA) of 1997—Chile’s first Free Trade Agreement (FTA) and Canada’s first FTA outside of North America25—which facilitated Canadian investments into Chilean mining, private utilities, and other sectors. Today, Canadian mining companies are some of the biggest stakeholders in Chilean mining, with over 40 mining companies overseeing more than 100 mines and projects in the country.26 Many of the companies, including Teck Resources, Barrick Gold, and Kinross, have been accused of violating Indigenous sovereignty and rights, committing environmental crimes, and/or tax evasion.27 While impacting communities and ecologies in Chile, these companies’ profits are quickly transferred to downtown Toronto, where most of them are headquartered and traded via the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX) and the TSX Venture Exchange (TSXV).28

Carmen de Andacollo (2021) is part of Soledad Muñoz’s series Las Heridas de Chile (The Wounds of Chile, 2021). This piece is made of copper threads and uses the technique of double-weave to represent an open-pit mine owned by Teck Resources, a Canadian mining company operating in the Coquimbo Region of central Chile. The mine’s open pit is located merely a few metres from the local community, just about the distance between Sur Gallery and the company’s headquarters in downtown Toronto.

When browsing through the archives at the Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos in Santiago, I was surprised to find this report, in Spanish, written by the Canadian Taskforce on the Churches and Corporate Responsibility (TCCR) in 1978. The document singles out the main Canadian multinational corporations that enabled and benefited from the repressive environment in Chile. Specifically, the TCCR explains that the Royal Bank of Canada, the Toronto Dominion Bank, and the Bank of Montreal provided credit lines and loans to the regime, while Falconbridge Nickel and Noranda Mines planned major investments in copper mining. Queen’s University had stocks and bonds in Noranda at the time, provoking what the Taskforce document describes as an ardent reaction from students and human rights groups tied to the university, including debates about the social role of the university and two student referendums where students expressed their desire to divest from the mining conglomerate, which were not upheld by the leadership.29 After extensive delays, the university ended up divesting from Noranda by 1983 after the prices of copper plunged, explicitly citing the decision as a financial one.30 However, the campaign fomented further scrutiny of the university’s funding schemes, opening the door of divestments for future generations, such as those we are experiencing today regarding fossil fuel industries.31

The TCCR report also brings attention to the uneven socio-economic impacts that the dictatorship was having on Chileans—particularly historically marginalized communities—who endured harsh economic conditions, unemployment, and lack of access to essential services while local elites and multinational corporations cashed in. Finally, the document casts skepticism regarding the trust that the junta and its transnational supporters put in the reorientation of the Chilean economy towards exploiting natural resources.

These complexities are illustrated in the scenes presented in the arpilleras that are included in the document. The arpillera on the cover of the report is titled The Misery (artist and year unknown) and shows unhoused people sleeping in the streets. The report also includes two other pictures of arpilleras depicting life in poor and working-class neighbourhoods and a group of women rallying in front of the Court of Appeals. While the former highlights the economic impact of the dictatorship, the latter highlights the agency of women resisting the regime. These textiles challenge the junta’s effort to polish its international image “to attract the financial support that it needs to remain in power” (page 1 in the report).

Exports Diversification

While initially built around traditional exports like mining, Chile’s export-oriented model has since diversified its offering to include forestry, agro-industry, and fishing.32 The fishing nets of industrial salmon farming are also hilos conductores in this story.

When I invited Memorarte to participate in this exhibition, the group’s director Erika Silva shared that while working with Greenpeace in a campaign against salmon fisheries in the Chilean Patagonia, the group learned about the harmful effects of industrial fishing on marine ecologies.33 Chile is one of the biggest suppliers of salmon to Canadian markets, with imports growing by 22 percent in the last two decades. Meanwhile, Canadian fishing multinationals like Cooke Aquaculture operating in Chile are major players in the industry.34

Memorarte’s textile work for this exhibition, Salmones: pescado podrido (Salmon: Spoiled Fish, 2022), illustrates these transnational connections with a simple yet powerful design where salmon fish bleed out into a black background. The fish are tagged with the Canadian maple leaf.

Calls for a New Constitution

Demands for a new constitution have been at the centre of political protest in Chile since the return to democracy. However, it wasn’t until the recent social revolt in 2019 that this opportunity materialized via a series of national referendums. As part of this process, Chileans voted overwhelmingly in favour of the project in the first plebiscite (October 2020) and elected a constitutional assembly in the second (May 2021). The elected assembly was internationally praised for ensuring gender parity and the representation of Indigenous communities within its membership. A year later, the assembly presented a draft of the new constitution, which was celebrated for its ambitious attention to issues of environmental and social justice. However, the efforts for a new constitution suffered a major setback in the plebiscite that took place on September 4, 2022, when this version of the constitution was rejected by over 61 percent of electors.

When we invited Bélgica Castro to participate in this exhibition, she was closely following the constitutional plebiscite unfolding in Chile. As she has been doing since the 1970s when she started making arpilleras, Castro took to her threads to navigate the complex emotions triggered by this process and the rejection of the new draft of the constitution.

Castro’s arpillera for this exhibition brings together different time periods that trace the legacies of the dictatorship resulting in La noche más larga de Chile (Chile’s Longest Night, 2022). While the presidential palace burns in the background and the military police point their weapons at dissenters, Castro’s piece also conjures memories of hope. In commenting on the piece, she said,

I remembered two young detenidos-desaparecidos: Carlos Alberto Carrasco Matus and Michel Nash Sáez. [They] were two young soldiers that were brutally murdered for bravely standing with their people. Carlos Alberto Carrasco Matus was a soldier that used his position as a prison guard to connect with the detained, comforting and giving them hope. Michel Nash Sáez was a soldier that refused to shoot prisoners. I dedicate my arpillera to them with all my love and in recognition of their bravery.

A ballerina dressed in red dances over the flames where the draft of the new constitution burns, perhaps prefiguring the end of Chile’s decades-long night.

Water

The development of major natural resource industries in Chile was predicated on the commodification of water, which is essential for their functioning. This was accomplished through the 1981 Water Code, which was imposed under authoritarian rule to allow the unregulated trade of water rights for “higher value uses.” Four decades after the implementation of the Water Code, 95.8 percent of the Chilean population is served by privatized water and sanitation services.35 Jessica Budds succinctly summarizes the uneven outcomes of the 1981 Water Code:

[One] hydroelectric power company acquired almost all the nonconsumptive rights in southern Chile, essentially preventing the entry of competitors; mining companies promptly acquired water rights for potential future projects in northern Chile, in some cases registering water being used by Indigenous groups, and commercial farmers were able to obtain most new groundwater rights in central-northern valleys, to the detriment of peasants.36

Among the private holders of water rights is the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan (OTPP), which owns over 34 percent of the rights via the Essbio, Esval, and Aguas del Valle utility companies.37 While the OTPP has seen steady growth since its establishment in 1990, becoming one of the biggest pension funds in Canada and an influential actor in the global economy, Chile undergoes its thirteenth year of a mega-drought and entire communities regularly go without access to clean water.38

Some of the most fervent calls within social movements in Chile have been raised against the 1981 Water Code.

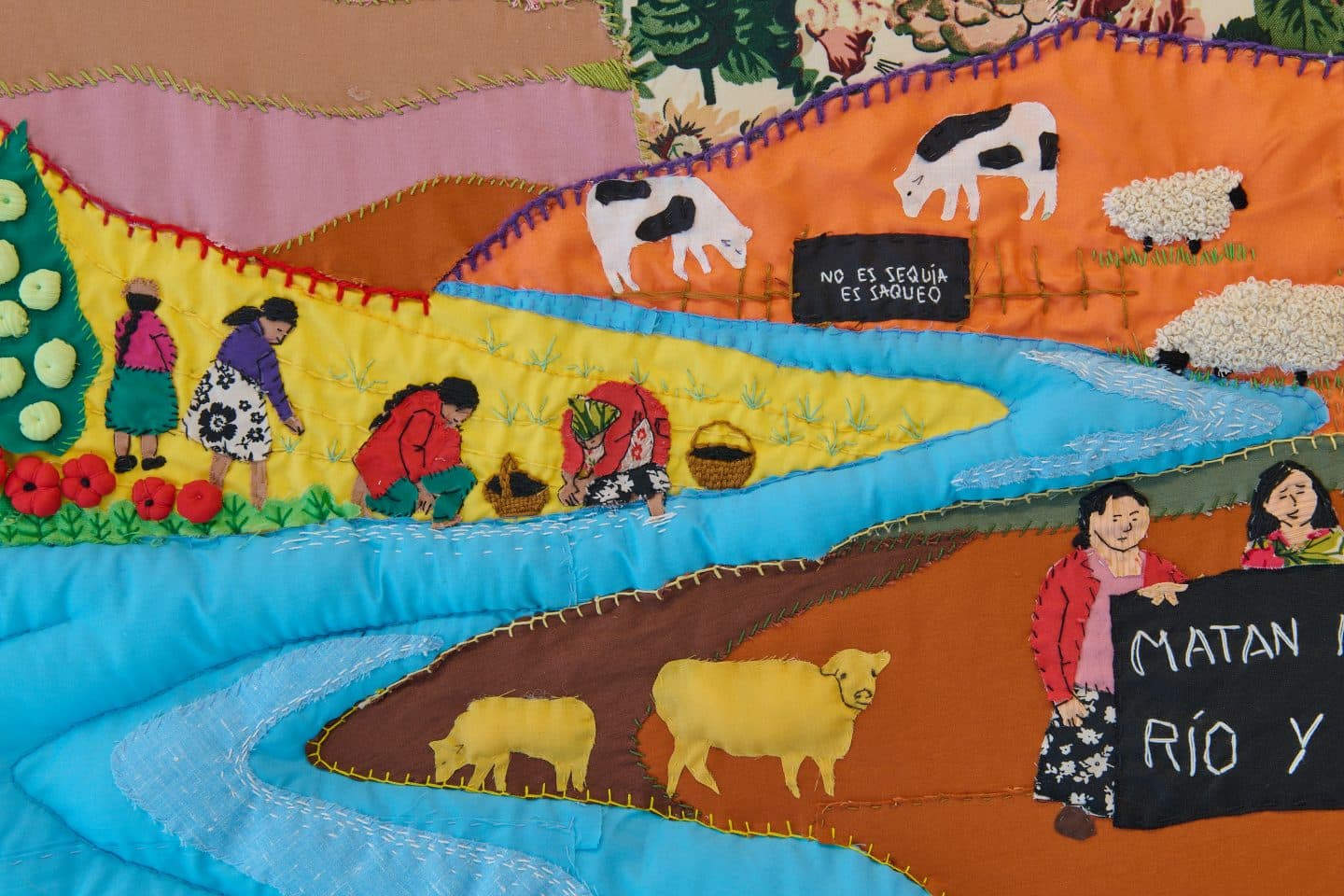

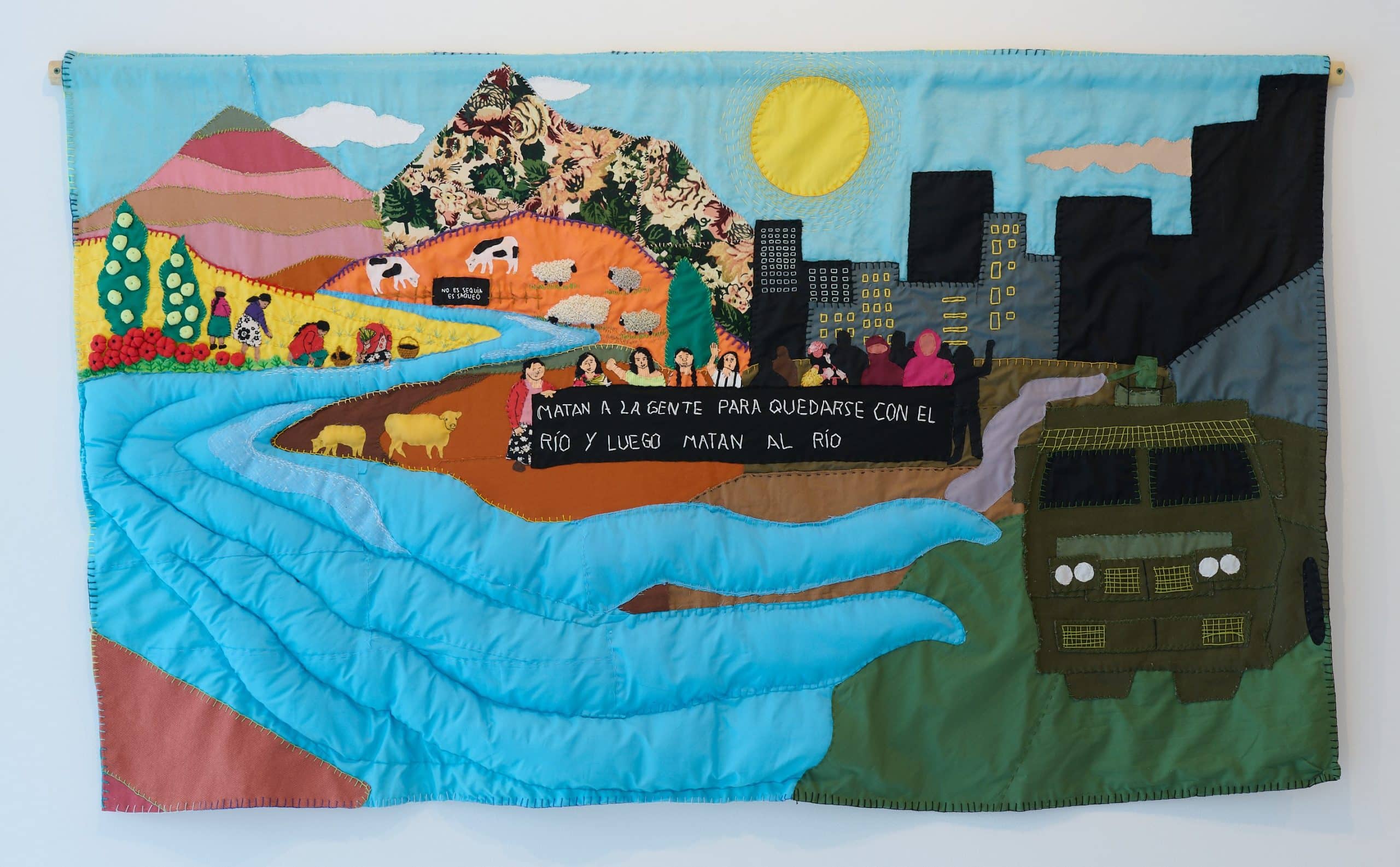

Tamara Marcos’s Agua dulce y libre (Fresh and free water, 2020) depicts a rural scene on the left side of the textile that gives way to an urban landscape on the right. The earthy-toned and patterned fabrics representing the land are crossed by the quilted stream of a blue river—undoubtedly the main character of the piece. In the background, women work in a garden, their bodies bent as they collect fruits and vegetables in baskets. A small flock of sheep grazes the hills while a little sign reminds us: No es sequía, es saqueo (It is not a drought, it is pillage).

The right section of the arpillera is more direct: as the river and the mountains give way to the city, we see a guanaco (water canon used by the state police) facing a group of women holding a sign that reads: Matan a la gente para quedarse con el rio, y luego matan al rio (They kill the people to steal the river, and then they kill the river).

While the piece depicts a rural scene where local practices and resistance are met with police repression, the struggles captured by this textile are wide-reaching, concerning the workings of the global economy. Just outside of the cultural centre where I saw Marcos’s piece for the first time in March of 2020, the streets of Santiago were covered in graffiti and banners that denounced the general depletion of natural resources and the handover of essential goods to private interests, both of which have been emblematic of the last 30 years of post-dictatorial neoliberalism in Chile. As I stood in front of Marcos’s arpillera I wondered about the types of reverberations that artworks like this could generate in distant geographies unknowingly entangled with the rural community and the river depicted in it.

Reimagining Collective Futures

Extractivism and solidarity are two types of relationships that connect distant geographies through mechanisms that are different but can become enmeshed nonetheless. Therefore, solidarity and the struggles for a more sustainable and just world require that we reckon with the uneven and often unexpected links that connect our lives and fates across the world.

While political textiles alone are not enough to undo the deeply rooted dynamics at the centre of supply chains and foreign investment schemes, hopefully they can help us tease out and disentangle the messy hilos conductores that inform our collective futures.

Art can also help us reimagine ecological relations in alternative, non-extractive terms.

Autorretazo’s works recast extractive approaches to water regarded as a resource that can be owned and exploited. The latter approach is represented in the bottom of Le pertenecemos al agua (We belong to water, 2022), with animals dying of thirst and hunger in a bare landscape. However, as we move up the textile, we see green forests and small agro-ecological activities that work in harmony with nature. A Mapuche woman holds Article 140 of the 2022 draft of the constitution, which states that water is essential to life. At the centre, water is personified holding the heart of nature. The title of the piece, which is embroidered onto the foreground, reminds us that water doesn’t belong to us, we belong to water.

After the Hilos Conductores exhibition is over, the textile pieces presented here will continue their trajectories, connecting personal histories with local struggles and distant geographies.

_____

Endnotes

_____

Works

woven textile with copper threads.

Carmen de Andacollo is part of Soledad Muñoz’s series Las Heridas de Chile (the Wounds of Chile). This piece is made of copper threads and uses the technique of double weave to represent an open pit mine owned by Teck Resources, a Canadian mining company, in the Coquimbo Region of central Chile. The opening of this mine is located just a few metres from the local community, closer than the distance from Sur Gallery to Teck’s headquarters in downtown Toronto.

applique, embroidery, and crochet on fabric.

People climb electrical posts to get copper, which is then bought and sold on the underground market. While people represented in this piece are forced to sell copper for a few pennies, Chile is the world’s largest exporter of this precious metal, supplying 30% of this essential resource to global markets. However, the wealth that is amassed by copper extraction and exports is not redistributed evenly and is often relocated to investing countries thanks to favourable tariffs.

applique, embroidery and crochet on fabric.

People climb electrical posts to get copper, which is then bought and sold on the underground market. While people represented in this piece are forced to sell copper for a few pennies, Chile is the world’s largest exporter of this precious metal, supplying 30% of this essential resource to global markets. However, the wealth that is amassed by copper extraction and exports is not redistributed evenly and is often relocated to investing countries thanks to favourable tariffs.

report.

This report identifies the main Canadian corporations that enabled and benefited from the Chilean coup. Specifically, the Royal Bank of Canada, the Toronto Dominion Bank, and the Bank of Montreal provided credit lines and loans to the regime, while Falconbridge Nickel and Noranda Mines planned major investments in coper mining. The report also highlights the socioeconomic impacts that the dictatorship had on many Chileans, who endured harsh economic conditions, unemployment, and lack of access to essential services while local elites and multinational corporations cashed in.

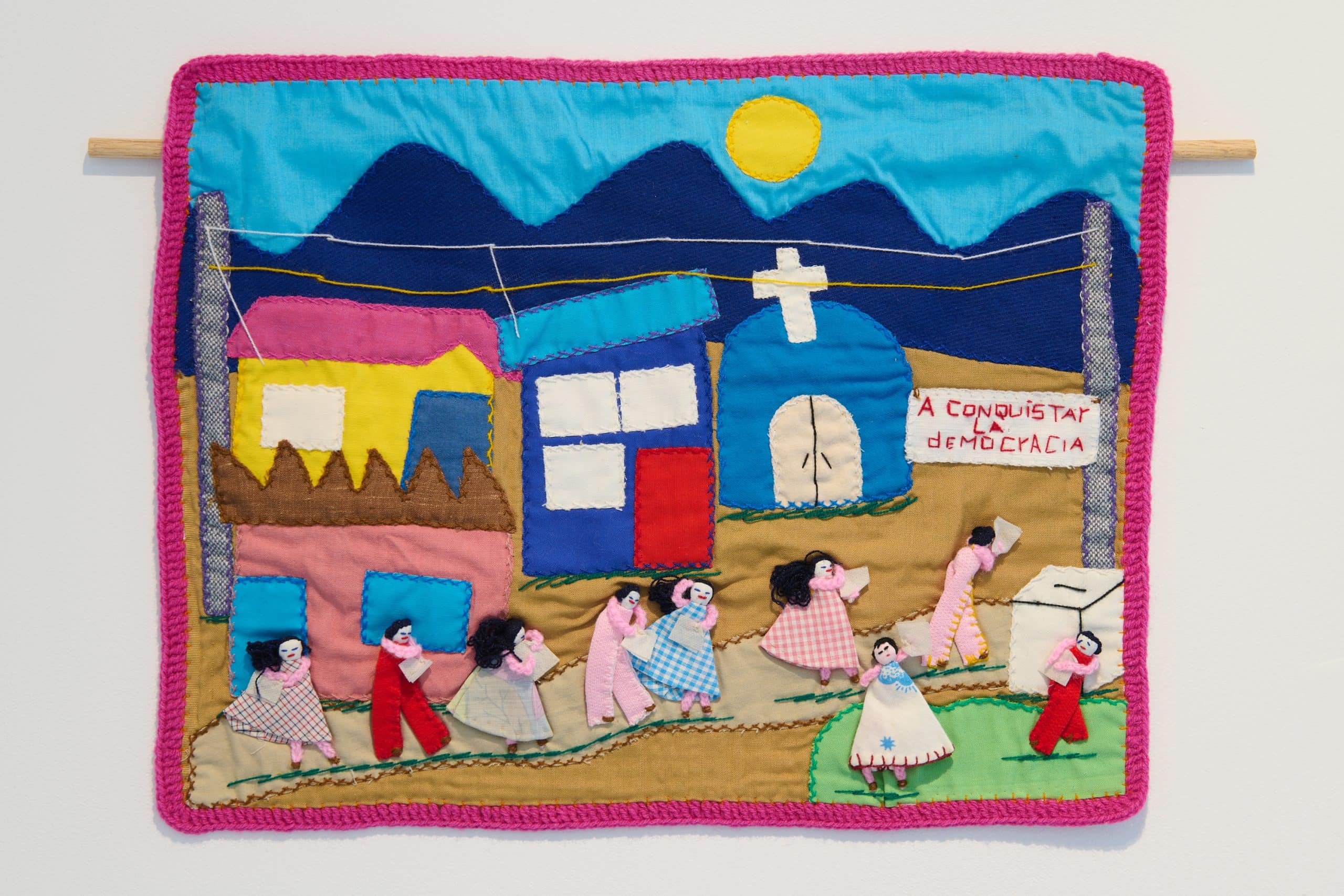

applique, embroidery and crochet on fabric.

A group of people line up to cast their ballots. The sign over the ballot box reads: A CONQUISTAR LA DEMOCRACIA (let’s regain democracy). In October 1988, Chile held a constitutionally mandated plebiscite to decide weather Pinochet could renew his mandate until 1997 or not. The “No” option won with 55.9 % of the votes.

applique, embroidery, and crochet on fabric.

A pair of women ask ¿DÓNDE ESTÁN? (where are they?), while a group of people behind them ask for justice for the detenidos-desaparecidos. During the Chilean dictatorship, thousands of people were forcibly disappeared by the state. Today, the whereabouts of 1,159 of them remain unknown.

applique, embroidery on fabric.

This arpillera shows the Presidential palace and the 2022 constitutional draft in flames while the police point weapons at dissenters, putting together two different timelines to connect the enduring legacies of the Chilean dictatorship. A ballerina dressed in red dances over the fire, perhaps prefiguring the end of “La noche más larga de Chile,” or Chile’s longest night.

Castro dedicates this arpillera to the memory of Carlos Alberto Carrasco Matus and Michel Nash Sáez.

applique, embroidery and crochet on fabric.

This piece is a self-representation of an arpillera workshop, where women gather to work on their arpillera projects.

applique and embroidery on fabric.

While initially built around traditional exports like mining, Chile’s export-oriented model has diversified its offering to include forestry, industrial agriculture, and fishing. Through this strategy, Chile has emerged as a key supplier of salmon to Canadian markets, and Canadian fishing multinationals like Cooke Aquaculture operate in Chile.

Memorate’s Salmones: pescado podrido illustrates these transnational connections with a simple yet powerful design where salmon fish bleed out into a black background, hinting at the harmful effects of industrial fishing on maritime ecologies, particularly in the Chilean Patagonia. Across the piece, fish are tagged with the Canadian maple leaf.

video, 23 minutes.

La parte de atrás de la arpillera documents the living contributions of arpillera makers in their own words. With footage from interviews with arpilleristas and from the 2019–2020 social revolts, this documentary shows how generations of arpilleras makers have been at the centre of anti-dictatorial and anti-neoliberal resistance in Chile.

applique, embroidery, and crochet on fabric.

This arpillera depicts a scene of community joy and hope. Children play and colourful flowers grow across the neighborhood.

applique, embroidery, and other elements on fabric.

Autorretazo’s piece challenges extractive imaginaries that view water as a resource that can be owned and exploited. In the bottom of the piece, animals die of thirst and hunger in a bare landscape. However, we also see green forests and small agro-ecological activities that work in harmony with nature, while a woman who might represent water offers the heart of nature. A Mapuche woman holds article 140 of the 2022 draft of the constitution, which states that water is essential to life. The embroidered message appliqued across the textile reads: “Water doesn’t belong to us. We belong to water.”

applique, embroidery, and quilting on fabric.

Tamara Marco’s Agua dulce y libre juxtaposes rural and urban landscapes, with the blue quilted stream of a river crossing the scene. In the back, women work in a garden while a small flock of sheep grazes the hills. A sign reminds us that: No es sequía, es saqueo (It is not a drought but pillage). In the foreground, a police vehicle faces a group of women that hold a sign that reads: Matan a la gente para quedarse con el rio, y luego matan al rio (They kill the people to steal the river, and then they kill the river).

Biographies

_____

Acknowledgements & Credits

This publication documents the exhibition Hilos Conductores curated by Nathalia Santos Ocasio and co-presented by Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Sur Gallery, and the Textile Museum of Canada.

Hilos Conductores

2 February–1 April 2023

Sur Gallery

39 Queens Quay E Suite 100

Toronto, Ontario

ISBN-13: 978-1-55339-683-3

Author: Nathalia Santos Ocasio

Coordinating curator: Sunny Kerr

Copy editor: Jack Stanley

Photographer: Rafael Goldchain

Digital project coordinator: Danuta Sierhuis

Alt-text writers: Charlotte Gagnier, Sonia Riabtchik, Alex Wilson

Design: Kelsey Blackwell

Citation:

Santos Ocasio, Nathalia. Hilos Conductores. Kingston: Agnes Etherington Art Centre, 2023.

© Agnes Etherington Art Centre 2023

All images are reproduced with the permission of the rights holders acknowledged in captions. These images may not be reproduced, copied, transmitted, or manipulated without consent from the owners, who reserve all rights.

Every effort has been made to identify, contact, and acknowledge copyright holders for all reproductions; additional rights holders are encouraged to contact Agnes Etherington Art Centre.