Salomon de Bray

Hagar Brought to Abraham by Sarah, 1650

Oil on panel

Gift of Alfred and Isabel Bader, 2010 (53-038)

The story of Hagar exemplifies the virtue of obedience to God’s will. Wishing to fulfill God’s promise to Abraham that he would beget many nations, the elderly Sarah offered her slave Hagar to her husband. Hagar gave birth to Ishmael, who would go on to found a great nation through his twelve sons. Salomon de Bray here evokes Hagar’s vulnerability through her nudity, her hunched pose suggesting her discomfiture, and through the physical guidance to her fate by the married couple.

Salomon de Bray

Hagar Brought to Abraham by Sarah, 1650

Nicolaes Moeyaert

Mercury and Herse, 1624

Oil on panel

Mauritshuis, The Hague (394)

The distinctive pose of Hagar’s naked body has clear precedent in the Western artistic tradition. The Amsterdam artist Nicolaes Moeyaert (1591–1655), with whom De Bray may have studied, included a similar standing nude figure in his 1624 painting of Mercury and Herse. Moeyaert, in turn, may have been looking at a figure in an allegory of fertility by Jacob Jordaens (1593–1678) of around 1623 (Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten van België, Brussels) and at a copy after the Aphrodite of Knidos by the ancient Greek sculptor Praxiteles (395–330 BCE). It was not uncommon for artists of this period to seek to surpass each other by cleverly adapting and reusing motifs in new contexts. As the Dutch theorist Franciscus Junius the Younger (1591–1677) wrote:

in my opinion, the artists who surpass all others are those who diligently pursue the old art with a new argument, thus adroitly bestowing their paintings with the pleasurable enjoyment of dissimilar similarity. 1

Such studio practices not only bred rivalry among artists that resulted in beautiful paintings but also engaged the attentive eye of the connoisseur.

1 Quoted in Eric Jan Sluijter, Rembrandt and the Female Nude (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2006), p. 263.

Crispijn de Passe the Elder

Venus, from the series Six Gods and Goddesses, 1592

Engraving

Purchase, Consolidated Purchase Fund, 1979 (22-012.5)

Though the nude female body long occupied the position of the highest accomplishment in art, not all members of early modern society believed in its aesthetic merit. The Dutch theologian and writer Dirck Volckertsz. Coornhert (1522–1590) made explicit his concerns about salacious imagery:

Imagine a beautiful nude Venus

What will it make churn in one’s mind but an unchaste fire?

Douse this spark before you go up in flames!

Swiftly extinguish this fiery image,

Abide firmly by your reason,

Such that it turns your eyes away from lust,

Because the sight of lust breeds evil desire. 1

As scientific theories of the seventeenth century privileged the eye as the point of entry of love and lust, the painted female nude proved particularly threatening.

Other writers, however, celebrated the erotic appeal of the nude body, pairing clever verses with paintings of nude nymphs and goddesses. The painter Dirck Bleker (around 1622–after 1672) depicted a now-lost nude Venus for the stadtholder of Holland. Joost van den Vondel (1587–1679) penned the words that Bleker’s goddess of beauty could have spoken to the owner’s wife:

If my nudity with its lifelike rays

Pierces His Majesty’s heart, this should not pain you.

Finding no hold on paint and life’s semblance

He will, inflamed by glowing heat, take vengeance upon you.

And if this agrees with you, do not despise me

But rather praise the excellence of the brush. 2

The erotic appeal of the female nude body was clearly acknowledged by seventeenth-century audiences—as a threat to chastity by some members of the religious community and as a source of visual pleasure by numerous connoisseurs—creating a fascinating tension of licit and illicit viewership.

1 Quoted in Eric Jan Sluijter, Rembrandt and the Female Nude

(Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2006), pp. 144–145.

2 Ibid, p. 149.

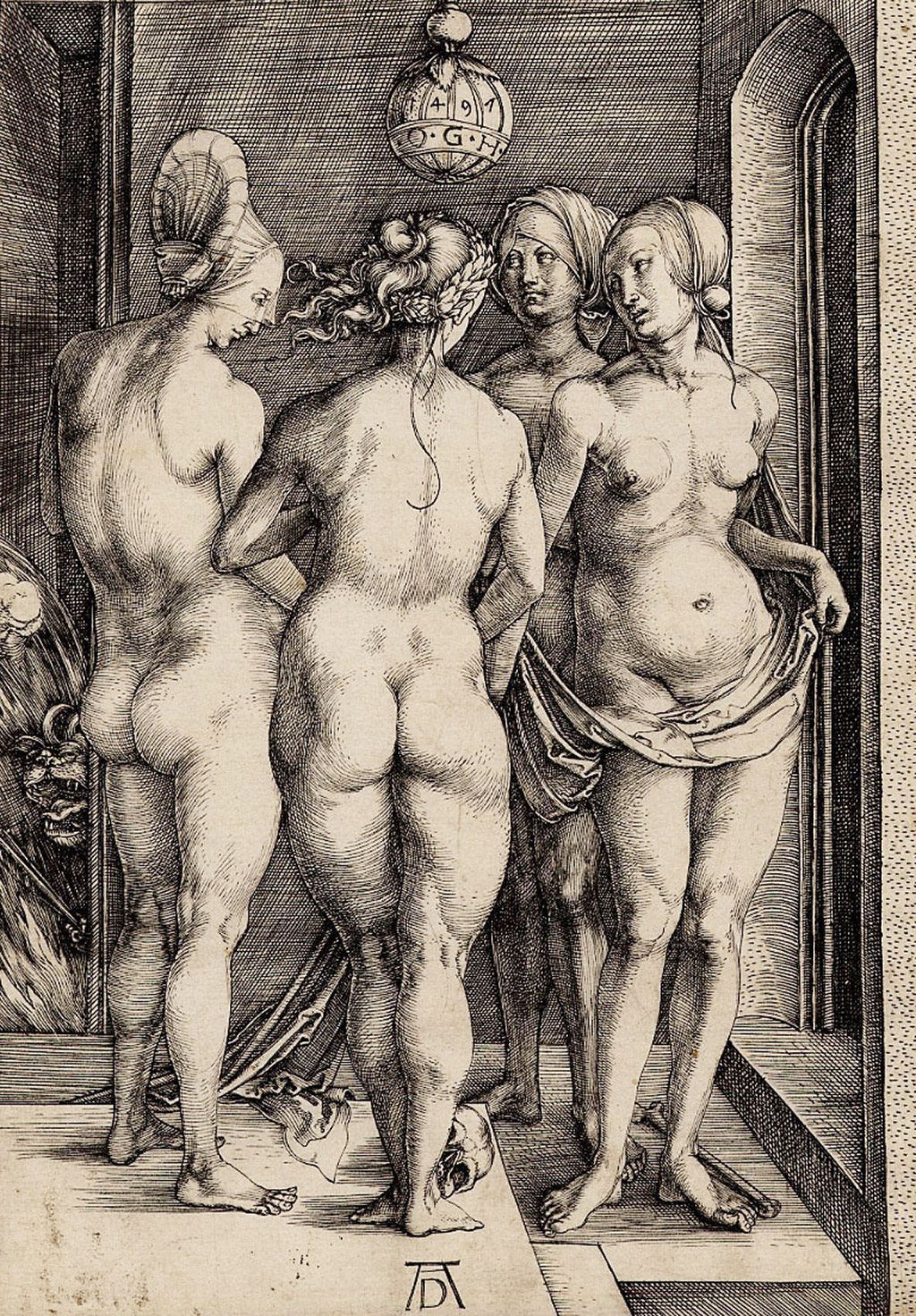

Albrecht Dürer

The Four Witches, 1497

Engraving

British Museum, London (E,4.128)

Goddesses and biblical heroines served as convenient narrative vehicles for the use of the female nude, yet the rise of witch imagery in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries foregrounded the female body as a symbol of sinister empowerment. The witch came to the fore of the collective consciousness with the publication of the Malleus Maleficarum (Hammer of Witches) in 1487 by Heinrich Kramer (around 1430–1505) and Jacob Sprenger (around 1435–1495). This handbook for the extermination of witches—between 100,000 and 200,000 accused were put to death across Europe around this time—outlines the alleged wicked character of these women. Their insatiability, combined with their deceitfulness and emotional instability, made them particularly threatening. With their demonic powers, they could render a man physically, financially and emotionally impotent. Female sexuality, as located in the socially indecorous nude body, became encoded with malevolence, indicated by the devil and human skull in the print by Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528).

The Powers of Women: Female Fortitude in European Art is curated by Dr Jacquelyn N. Coutré, Bader Curator and Researcher of European Art, and is organized by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, with the generous support of the Bader Legacy Fund, the Bader Conservation Fund and the George Taylor Richardson Memorial Fund, Queen’s University.

Photo credit for Agnes works: John Glembin

Photo credit for British Museum works:

©Trustees of the British Museum