Gerbrand van den Eeckhout

Solomon’s Idolatry, around 1665

Oil on canvas

Gift of Alfred and Isabel Bader, 2013 (56-003.15)

Solomon’s wives appear in the literary tradition of the power-of-women topos as early as the twelfth century. The first book of Kings recounts that God granted the monarch wisdom but that Solomon failed to apply it to his hundreds of wives. His love for these women, who came from foreign lands, caused him to abandon God in favour of their idols. The biblical text notes that Solomon succumbed to their religious fervour in his old age, thereby invoking the moral weakness that could accompany the physical decline of men in their later years.

Gerbrand van den Eeckhout

Solomon’s Idolatry, around 1665

Quentin Massys

Ill-Matched Lovers, around 1520–1525

Oil on panel

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund (1971.55.1)

The notion that female beauty could overcome man’s rationality is fundamental to the power-of-women theme, but the literary concept of a young woman seducing an older man became popular in the visual tradition of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Writers since antiquity had satirized the pursuit of younger women by older men as a laughable overestimation of masculine potency. As a visual theme, however, it allowed an artist to demonstrate painterly prowess in the differentiation of old age through wrinkled skin, missing teeth, and pulsing veins.

This interpretation by Quentin Massys (1466–1530) demonstrates that a young woman’s attentions can have not only a spiritually corruptive effect, as in Van den Eeckhout’s painting, but also a financially deleterious one. Blinded by his shameless lust, the old man sacrifices not only his rectitude but his purse to the alluring girl and her jeering companion.

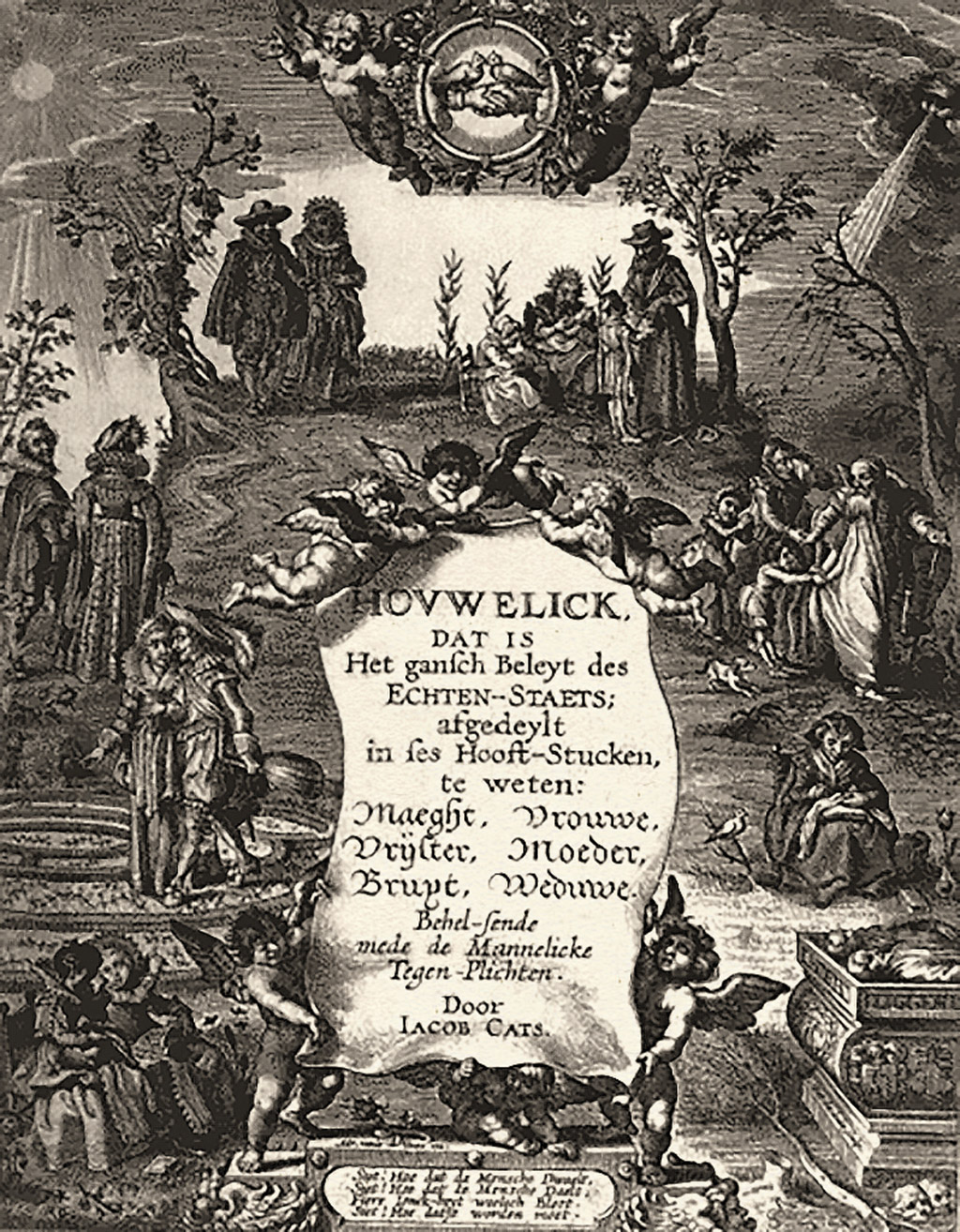

Title page of Jacob Cats’s Houwelick

1625

Published by Jan Pieterss vande Venne, Middelburg

Bibliothèque municipale de Lyon (SJ BE 101/16)

In contrast to the conduct of Solomon’s wives, the virtuous wife in early modern Holland was a spiritual and social companion to her husband. The Dutch poet Jacob Cats (1577–1660) wrote in his manual Houwelick (Marriage) of 1625 that man should desire:

A wife that honors neighbors close

But seldom out of doors doth go

A wife, a still and peaceful wife

A foe to all that’s woe and strife

A wife that never breaks the peace

And ne’er too loud or shrill of speech,

A wife who’d rather suffer pain

Than cry or utter a vile name

A wife that never grunts with food

Or goes into a pouting mood. 1

These verses praise the qualities of obedience, restraint and courtesy, but earlier authors had also celebrated the virtues of piety, silence, humility and constancy. Van den Eeckhout’s composition, with the pagan women relegated to the background and Solomon worshipping independently, playfully inverts Cats’s ideal.

1 Quoted in Simon Schama, The Embarrassment of Riches: An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age (New York: Vintage Books, 1997), p. 398.

Emanuel de Witte

Interior of the Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam, 1680

Oil on canvas

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (SK-A-3738)

While the tale of Solomon’s worship of idols is meant to warn against polytheism, the religious plurality it illustrates had clear parallels with the social fabric of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Intercontinental trade and political instability resulted in multicultural populations in many European cities, including Amsterdam. The city had become a safe harbour for Jews from Spain and later from Eastern Europe after a 1619 decree permitted Dutch cities to welcome the settlement of Jewish refugees. Paintings of Jewish cemeteries and famous synagogues abounded in the middle of the century, suggesting not only a civic pride in toleration of religious diversity but an appreciation of the aesthetics of religious apparatus.

In 1670, the Sephardim (Jews with roots in the Iberian Peninsula) of Amsterdam began plans for a new synagogue. The grand house of worship became a major tourist attraction for Jews and Christians alike. In this painting of it by Emanuel de Witte (1617–1692), non-Jewish visitors to the synagogue occupy the foreground. As in Van den Eeckhout’s painting, in which Solomon’s pagan wives are not clothed in strikingly foreign garb, little difference in clothing is evident between the Dutch Christians and the Jewish “other.” The only distinguishing Jewish garments are the prayer shawls. Unlike other cities, Amsterdam did not require its Jewish citizens to wear badges or other paraphernalia, another indication of the city’s liberal attitude.

The Powers of Women: Female Fortitude in European Art is curated by Dr Jacquelyn N. Coutré, Bader Curator and Researcher of European Art, and is organized by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, with the generous support of the Bader Legacy Fund, the Bader Conservation Fund and the George Taylor Richardson Memorial Fund, Queen’s University.

Photo credit for Agnes works: John Glembin

Photo credit for British Museum works:

©Trustees of the British Museum