Gerbrand van den Eeckhout

The Fall of Man, 1646

Oil on panel

Gift of Alfred and Isabel Bader, 2013 (56-003.14)

Unlike many early modern interpretations of the fall of man, Eve’s agency is expressed here through her central placement, standing pose, extended hand and illuminated body. Gerbrand van den Eeckhout took over many of these elements from his master, Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669), but Van den Eeckhout lightens Rembrandt’s serious atmosphere through the almost cheerful engagement between the two figures. Nothing but the war between the cat and dog alludes to the imminent ruin of mankind.

Gerbrand van den Eeckhout

The Fall of Man, 1646

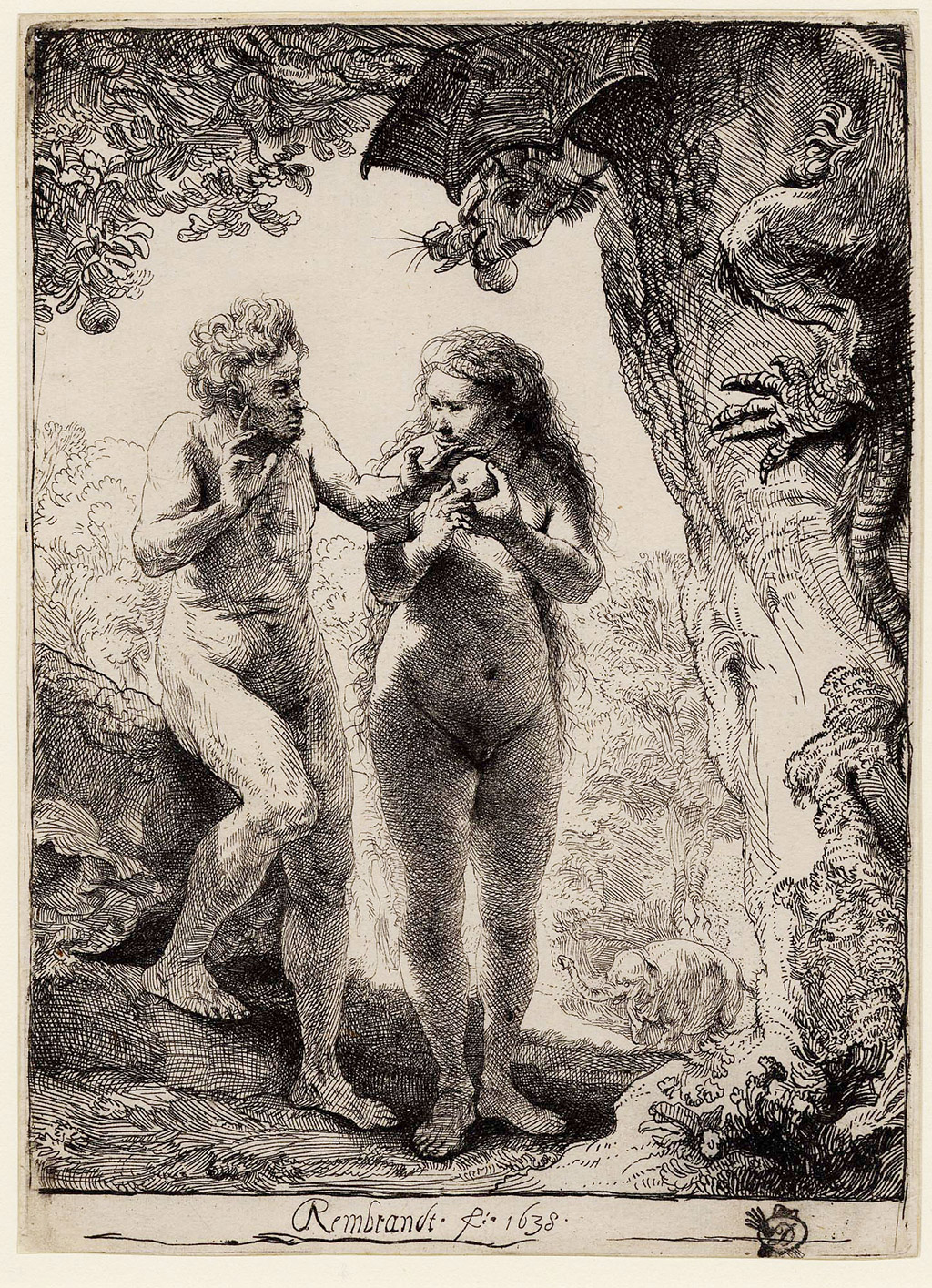

Rembrandt van Rijn

Adam and Eve, 1638

Etching

British Museum, London (F,4.40)

As scholars have observed, Rembrandt’s interpretation of this subject focuses upon the psychology of temptation. Eve turns her gaze slyly to her companion as she passively proffers the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge with both hands. Adam, in turn, assesses: he raises his right hand as if calculating the consequences of the situation. Directly below the apple is Eve’s shadowed pudendum. This motif, which is entirely hidden by Eve’s flowing hair in Van den Eeckhout’s painting, may reflect the influence of Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa’s treatise De originali peccato disputabilis opinionis declamatio (printed 1529). This text postulates that the sexual act, and not the disobedience of God as taught in previous centuries, was the true original sin. With her feet turned outward and firmly rooted posture, however, Eve offers sexuality without eroticism.

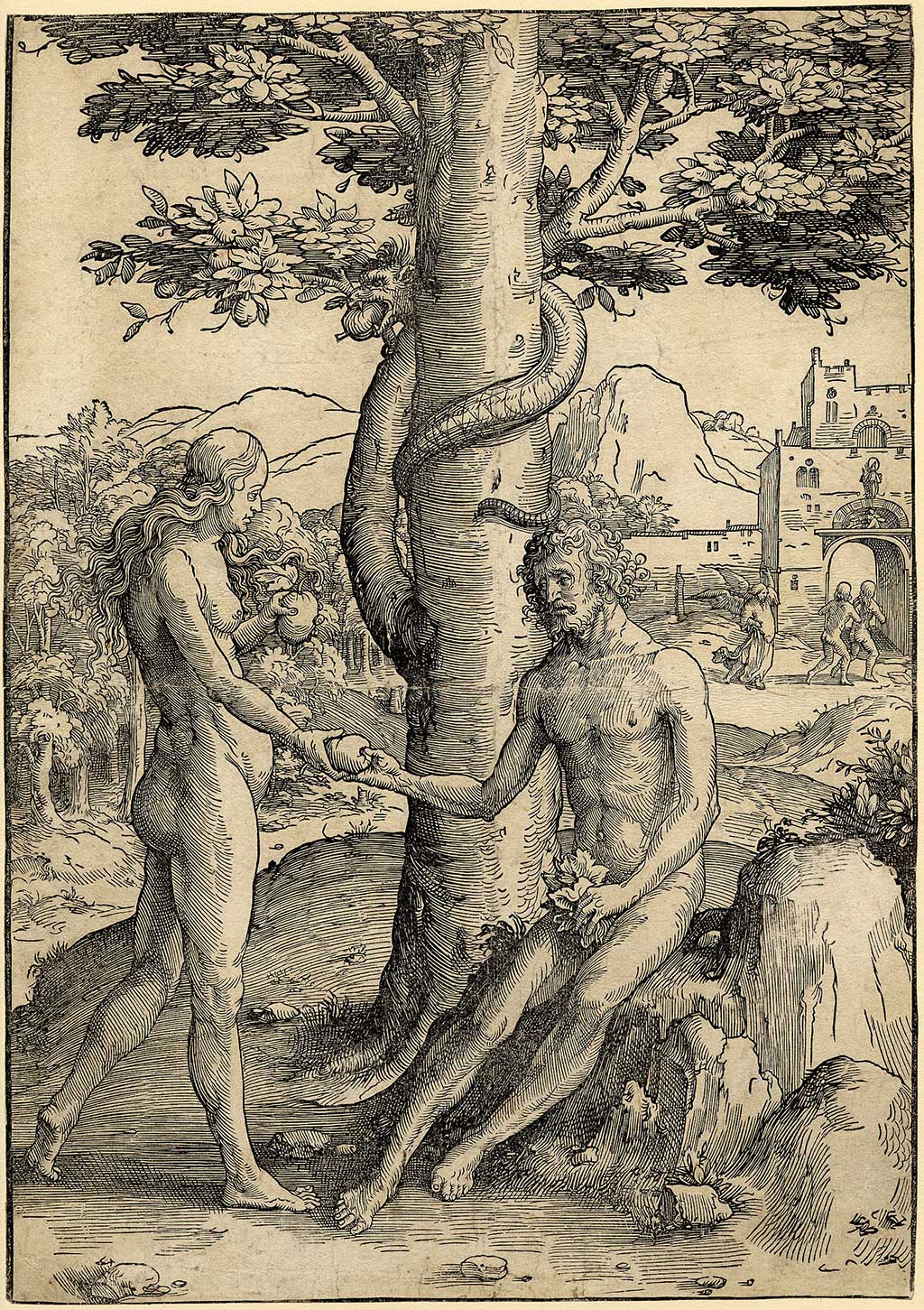

Lucas van Leyden

The Fall of Man, from the series The Large Power of Women

Around 1514

Woodcut

British Museum, London (1849,1027.84)

The visual manifestation of the Weibermacht (power of women) theme has its origins in thirteenth-century decorative objects like ivory caskets and manuscript marginalia, but it flourished in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries through the easily circulated medium of the print. The Netherlandish artist Lucas van Leyden (1494–1533) depicted the theme through two woodcut series known as The Large Power of Women (around 1512–1514) and The Small Power of Women (around 1516–1519). Lucas’s series were the first to incorporate Eve into the visual topos, thereby linking her transgression with women who deliberately sought to deceive and betray unsuspecting men. In Adam and Eve, from The Large Power of Women, the blame that Eve bears for the downfall of man is reinforced through the background scene illustrating the ejection of the first couple from Paradise.

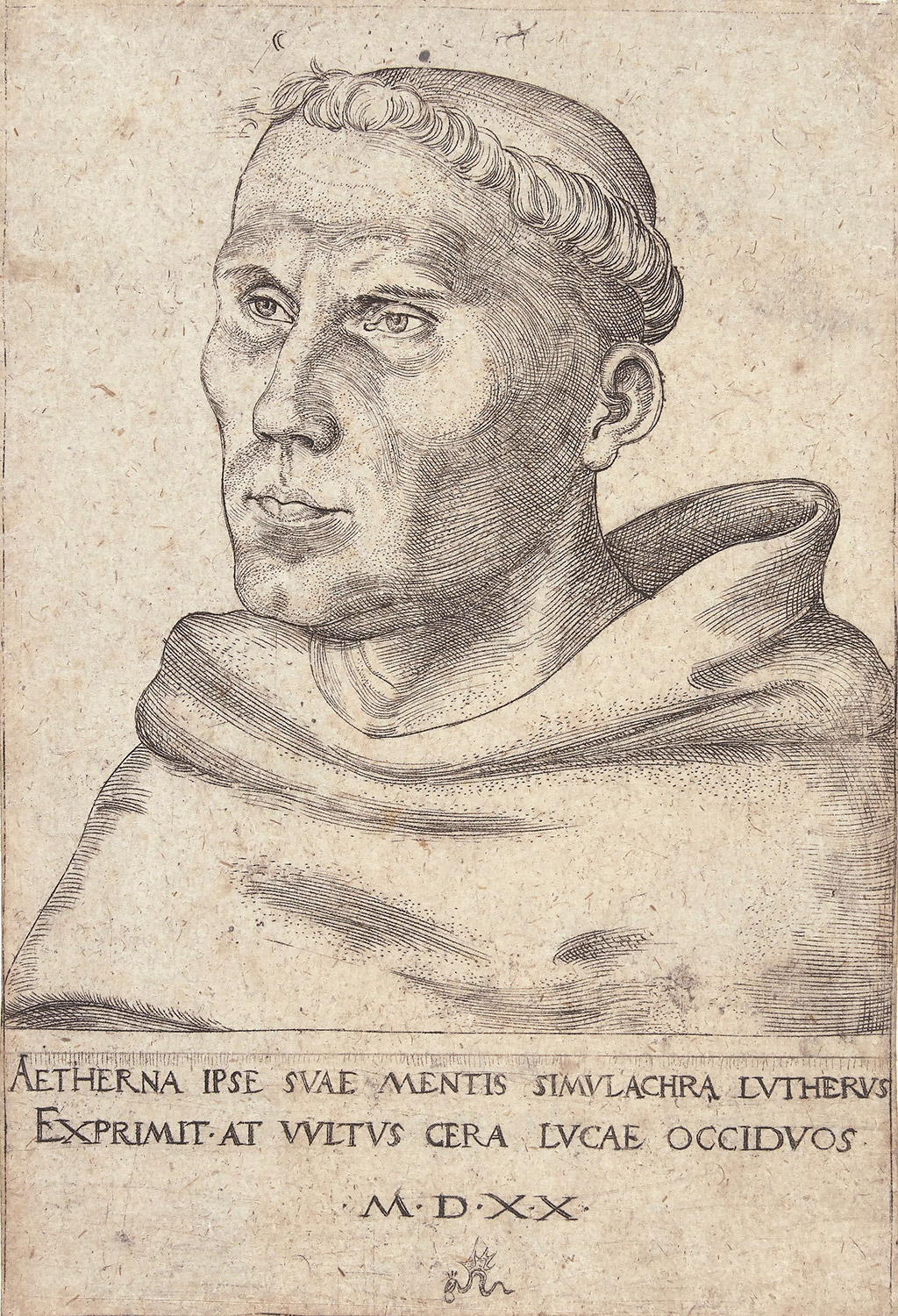

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk, 1520

Engraving

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (RP-P-1919-1988)

For the theologian Martin Luther (1483–1546), whose ideology influenced the denominations of Christianity popular in the Dutch Republic during Van den Eeckhout’s time, Eve’s wickedness resided in her vulnerability to temptation. In his Sermons on Genesis in 1527, he wrote:

Adam, [St.] Paul says, was not seduced but rather the woman. But because he also transgresses, he makes the sin all the heavier and more gruesome. She was a fool, easy to lead astray, did not know any better. But he had God’s word before him. He knew it well and should have punished her. But he stands there, looks on, and eats too, wantonly giving his consent to the devil’s advice. 1

Though Luther understood the value of woman’s role as wife and mother, he acknowledged that it was the irrational and highly susceptible nature of woman that led Eve to be seduced by the serpent. Her single act of folly, which led to the expulsion from Paradise, ultimately made her responsible for all human suffering.

1 Quoted in Susan C. Karant-Nunn and Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks, eds., Luther on Women: A Sourcebook (London: Cambridge University Press, 2003), p. 21.

The Powers of Women: Female Fortitude in European Art is curated by Dr Jacquelyn N. Coutré, Bader Curator and Researcher of European Art, and is organized by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, with the generous support of the Bader Legacy Fund, the Bader Conservation Fund and the George Taylor Richardson Memorial Fund, Queen’s University.

Photo credit for Agnes works: John Glembin

Photo credit for British Museum works:

©Trustees of the British Museum