Margaret, Jessie and I: Queer Aesthetics of Desire in Re-presenting the Female Nude

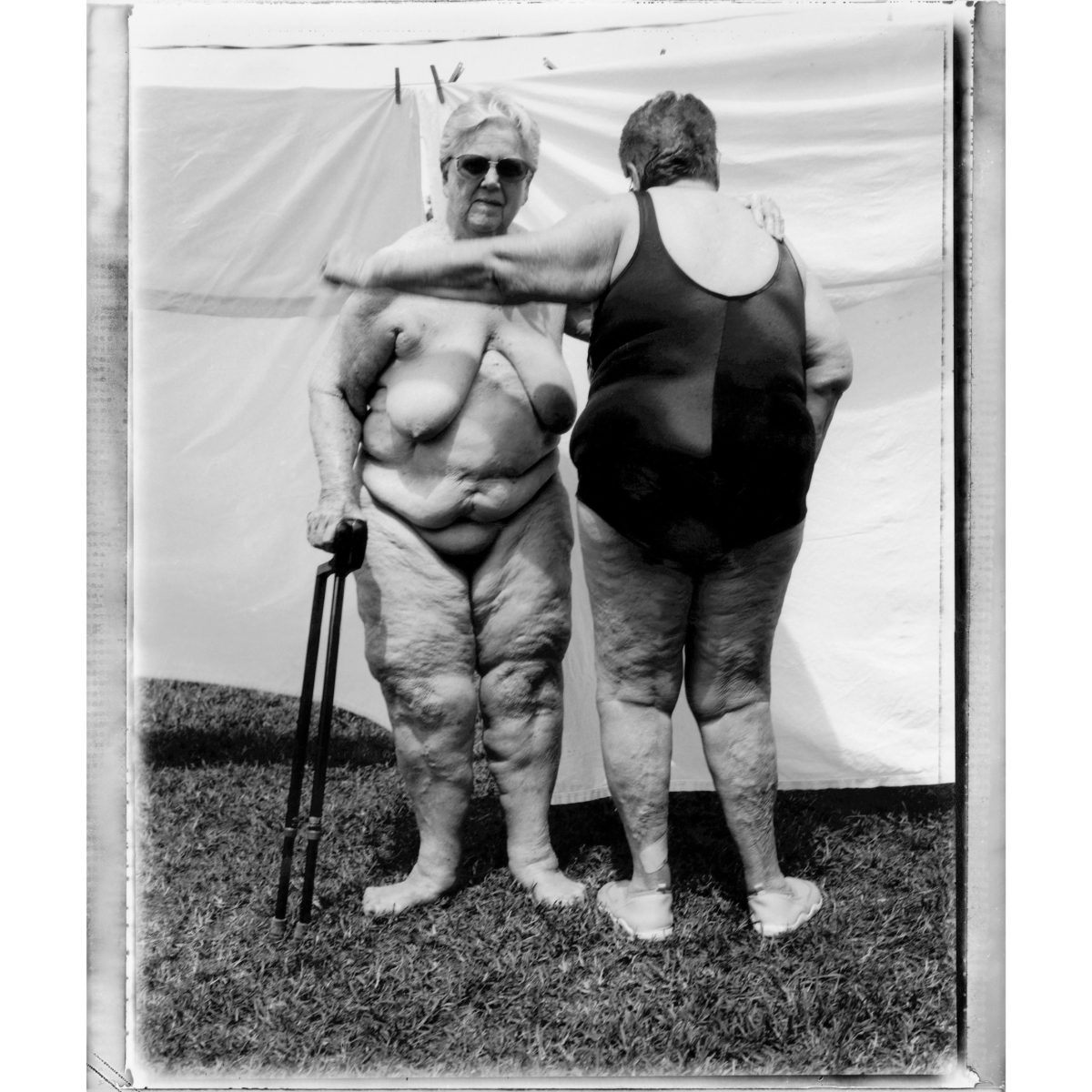

Canadian artist Evergon’s (b. 1946) photograph, Margaret & Jessie (Florida) (2001), queers the performance of gender and sexuality by expressing homoerotic sensuality and agency through mature female bodies.1Evergon, Margaret & Jessie (Florida), 2001, black & white silver gelatin print. Purchase, Canada Council Acquisition Assistance Fund and Chancellor Richardson Memorial Fund, 2003 (46-011) In it, two women, both visibly aging, stand poised to complete an embrace. One is totally nude/naked holding onto two walkers in her right hand as her left hand grips onto the shoulder of her swimsuit-clad companion who, with her back turned to the camera, is also motioning to embrace, her left hand a soft blur. The double portrait questions normative conventions of gender, sexuality and desire, opening them up to scrutiny and eventual redirection of what it means to be seen and understood as socio-culturally female. Further, the work allows its audience to examine the strictures of one’s identity within and outside narrow structures of gender, age and sexuality. Conservative and stable definitions of these structures are neither preferred nor encouraged by Evergon’s representation of the couple, leading to critical ambiguities around expressions and perceptions of gender, age, race, sexuality and desire. The depiction of Margaret and Jessie’s relationship, while somewhat undecidedly sapphic,2Sappho of Lesbos (c.630–c.570 BCE) was an Archaic Greek poet after whom the term “sapphic” is coined. She is famed for her lyric poetry that explored her love of women. A lesbian tour de force, she has come to symbolize, for many, the sometimes emotionally tumultuous journeys of love and desire between women. generates limitless and varied understandings of queer aesthetics of desire (i.e. homoeroticism and sapphic yearning) that are sustained by the uncompromising figures of the two women as simultaneously nude and naked (nude/naked).3In this essay, I propose that the figures of Margaret and Jessie are concurrently nude and naked, based on John Berger’s definitions of nudity and nakedness. In Ways of Seeing (British Broadcasting Corporation and Penguin Books, 1972), Berger argues that to be nude is to show off one’s body in a sexual way, to attract attention and be open to the judgment of others, while nakedness means to be one’s true self without care for how others judge their body. To express that Margaret and Jessie are both simultaneously nude and naked, I will be writing “nude and naked” as “nude/naked.” While Margaret is nude/naked in the typical understanding of what constitutes nudity and nakedness, I am positing that Jessie, though partially clothed, is also nude/naked. Relative to John Berger’s definition of the nude/naked, Jessie is nude because she is showcasing her body to the attention of others (be it sexual or otherwise) and so is open to their judgement. Concurrently, she is also naked because she is choosing how much of her body the audience can see and is not bound by the judgement and desires of others. Evergon, by boldly relating these elderly women to traditionally idealized female nudes and, in turn, re-presenting the nude as old and sapphic, highlights the absurdity of concrete gender binaries, including what constitutes femininity, “acceptable” sexuality, and the appropriate sexual desires of (aged) women/femmes within these categories.

Evergon’s camera captures an anticipatory moment––right before Jessie returns Margaret’s touch––charged with a current of sapphic yearning.4Sapphic yearning can be understood as the expectant interlude between sexual attraction and consummation that creates an intense feeling of homoerotic desire. Homoeroticism in general is defined as an instance “marked by (sexual) desire between people of the same sex.”5Merriam-Webster Dictionary, s.v. “homoerotic,” accessed November 7, 2024. In this photograph, it is expressed not strictly in terms of sexual desire but as desire itself in all its assorted forms, including in the impulse to touch and be touched, as demonstrated by the blur of Jessie’s hand as she reaches for Margaret and Margaret’s stable grip on Jessie’s shoulder. In this sense, Margaret and Jessie’s homoerotic interaction produces an erotic power that, for me, becomes the measure of myself and the knowledge of my own desire. They are subjects of my gaze and its wish to possess; I am enthralled by the decisive homoerotic power of their poses.6Audre Lorde, “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (Penguin Random House, 1972), 54. Here, I am referencing Lorde’s call to familiarize oneself with the erotic as a power that measures our connectivity with one another and ourselves. While I am actively looking at them and their nude/naked bodies, their hidden gazes acknowledge me but only insofar as they had expected an audience when they bared their bodies, outside and in front of a camera, an anticipation suggested by their different levels of undress. Margaret, confrontational with her nudity/nakedness, stares at the viewer through dark but somewhat transparent glasses. She retains her power in front of an audience by keeping her eyes partly shielded; I can slightly make out her eyes, but I cannot completely capture her gaze.

The reticent feelings of sapphic yearning, in this case the desire to be seen and to see, recur, now between Margaret, Jessie, and I. My relationship with Jessie—Margaret’s discreet double, who is markedly more reserved, with her hidden face and partially clothed body—is intercepted by her will. By turning her back to the camera and hiding her face, she is controlling how much knowledge of her I can possess. I become an observer of Margaret and Jessie’s intimacy, struggling to fully comprehend and pinpoint their relationship as it is not explicit, sapphic or otherwise.

I chose Margaret & Jessie (Florida) as a study of queer aesthetics of desire because the existence of unconventional bodies like mine (Black and fat) and theirs (elderly, fat, and ailing) usually unleashes a deluge of prejudices surrounding gender, age, race and sexuality. In my reflection on Evergon’s photograph, queer aesthetics of desire describe articulations of gender and sexual identities that showcase lived experiences beyond the binary of male/female and heteronormative hierarchies. There are endless expressions of gender and sexual identities and many iterations of beauty across ages and races and other differences. To express oneself as queer and to acknowledge the existence of gender and sexual identities outside heteronormativity is revolutionary—it generates the understanding that no one representation defines all lives, expressions and experiences. As I look at Margaret and Jessie in this photograph, I witness a complex reciprocity between my intimate and public self, which is defined by my experiences and self-expression regarding my age, race, gender and sexuality. I exist in an unconventional female body, as do Margaret and Jessie. We are each defined by our nonconformity to sociocultural conventions. To me, they exude sapphic energy, prompting me to become attentive to my body (how it feels and is seen by me and others) and its relationship to my self-expressions beyond established binaries. Margaret’s and Jessie’s bodies here are at once fantastically sensual because they are nude/naked women, but they are also ideologically unruly because they are fat and old women. They expand ideas of female sensuality to include bodies like mine and theirs. Thus, they simultaneously dislocate femininity from its exclusive confines of youthfulness—decidedly firm and fertile—while shaping it into (queer) inclusive realities.

Margaret & Jessie (Florida) is part of Evergon’s series of black-and-white photographs, Margaret and I (2001), which began as a collection of “Margaret nudes” after Margaret, then 82 years old, asked her son Evergon why he no longer photographed her in the nude.7Margaret and I, 21 February–22 March 2003, Stride Gallery, Calgary, Alberta. In Margaret and I, Evergon shows her in a variety of poses reminiscent of classical female nudes, like Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1538) or the more revolutionary rendition of the female nude, Olympia (1863) by Édouard Manet. Unlike Venus of Urbino or Olympia, the depiction of Margaret and Jessie as nude figures in classical poses is radically subversive in its composition, especially in showing how Margaret and Jessie relate to each other. Their poses mimic the standing classical nude, with their slight contrapposto stances, such as in The Three Graces by Peter Paul Rubens (1630–1635 (fig. 1). However, in Evergon’s photograph, Margaret and Jessie are deliberately arranged to interact and face each other such that they appear to mirror each other; their bodies, similar in type and appearance, overlap, suggesting familiarity, yet their standing apart asserts their independence.8Mirroring and doubling have been used as a visual code to indicate same sex desire, for example in Gluck’s Medallion (1937) or Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers) (1991). To me, they appear as doppelgängers, extensions of one another and ideologically indestructible.9In his essay, The Uncanny, Austrian psychologist Sigmund Freud argued that through the double, one is able to extend oneself; having a doppelgänger means that one is indestructible. Their bodies, similarly rippled with cellulite and ribbons of varicose veins, differ from each other in that Margaret is totally nude/naked and Jessie is partially clothed and wearing light coloured sneakers. In my interaction with Margaret and Jessie my inability to effectively capture their gazes and entirely possess knowledge of them and their relationship preserves the intimacy and familiarity of their gestures. However, some aspects of their relationship are made public to me. I am a distant participant with a longing to comprehensively seize onto their sensual intimacy and express my own desire.

Meditating on Margaret & Jessie (Florida), I come back to my body, my expressive self and my disparate experiences with a profound sense of empowerment. I become strong in the fact that while the marginalization of my body is expounded by the empirical fact that I am fat, Black, and female, it is not inherently possessed by white-centric heteronormative external definitions and understandings of what means to be fat, Black, and female/femme. I retain my autonomy to utilize my self-expressions and experiences within and outside typical sociocultural conventions. Yes, Margaret and Jessie are white and elderly whereas I am unambiguously Black and still young, yet there is significant power in our differences. I have the social currency of being young, if not thin and white, and they have the social capital of being white. Our overlapping realities of fatness and similar gender expressions, in combination with our independent entities, affirm that beyond the hierarchical binaries imposed by a culture and society that determines ideal body types, genders and racial identities, are numerous truths and ways of expressing oneself. The ideologically indestructible aspect of Margaret and Jessie’s pose as compositional doubles extends beyond them and is also reflected in me. The not quite circular composition (Margaret and Jessie have not yet completed their embrace) becomes a mirror that replicates, ad infinitum, varied realities. Our interactions through the photograph might be reticent yet candid expressions of (sapphic) yearning that blossom within shared female sensuality, but it is more nuanced and powerful because that is not the only aspect of our relationship.

Ultimately, Margaret & Jessie (Florida) surfaces the limitless articulations of queer aesthetics of desire by showing these women as doubles that reflect and recognize differences as well as similarities, allowing its audience to also subvert typical readings of homoerotic desire. Once understood as strange or peculiar, the term “queer” has become an expansive way of embracing marginalized bodies and sexualities that defy restrictive binaries. In this photograph, it defines a longing to be seen as yourself, publicly and privately. In Evergon’s practice of re-presenting the female nude, in Margaret & Jessie (Florida) in particular, gender constructions are not “violent and repeated circumscriptions of cultural intelligibility” that determine which bodies and sexualities matter.10Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex” (Routledge, 2011), 4. Margaret’s and Jessie’s bodies are not youthful and supple, the folds of flesh that envelope them are not flirtatious blush tones of pink, their sexualities are not tied to fertility or to ensuring the sexual arousal of a presumptive male audience, but they matter. Their bodies are evidence of inevitable aging but their spirits, who they are, remain sensuously virile, unencumbered by the marginalization of unconventional (female) bodies. The concurrent public and anonymous displays of Margaret’s and Jessie’s bodies and sexualities allows me as their audience to participate in a limited way that empowers them. This also reveals the power in laying claim to one’s body and sexual expression, publicly and privately.

Writer Audre Lorde discusses the importance of using the erotic as a shared source of power to create a basis of an understanding of difference that lessens the threat of difference. By incorporating this knowledge here, and acknowledging the difference between Margaret, Jessie, and I, I dismantle external and internalized hierarchies of race in which Margaret and Jessie as white women occupy a more privileged space within our interaction. They maintain their individual power and I, as a Black woman, retain mine. Our shared similarities and differences form a bridge between and beyond us; this bridge lessens the threat of difference that usually breeds violence. As I embrace Margaret and Jessie, my acknowledgement of our differences and similarities becomes a source of significant (erotic) power.