The Anarchist Free School emerged in the 1990s as a transformative experiment in radical education. Spearheaded by activists and artists, the school operated as a site of “collective coming into being,”1Luis Jacob, interviewed by the author, 1 September 2024. as Luis Jacob remarks, where participants could reimagine education without hierarchies and control. Jacob’s installation Anarchist Free School Minutes, 1999 delves into the motivations, structure and legacy of the Anarchist Free School, exploring the educational ethos that shaped the school’s practices and the significance of documenting its history, not just as an act of cultural preservation, but as a way to continue this legacy of DIY spaces outside of repressive institutional structures.

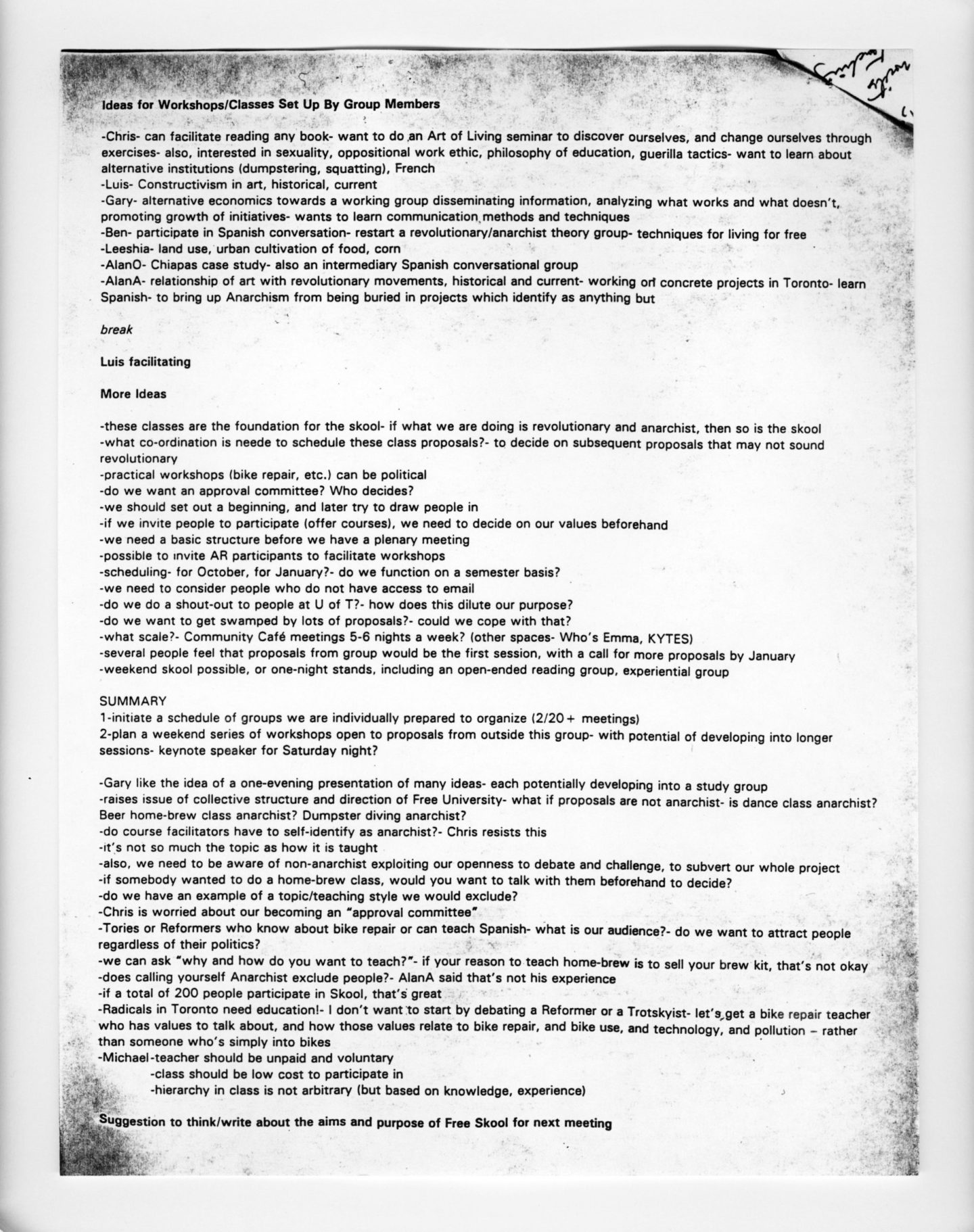

Jacob traces the origins of the Free School to the energy sparked by various gatherings, conferences and activist movements, particularly the “Active Resistance” event in the 1990s that drew over 500 participants from across North America. As Jacob recalls, the Free School emerged from a desire to carry forward the dynamic community organizing that took place in these gatherings, where participants would “figure out what [they] wanted to do together and what it would be.”2All subsequent quotes/reflections are from the interview with Jacob unless otherwise noted. This spontaneous, collective spirit evolved into a weekly meeting space that redefined the process of learning and teaching within a community setting.

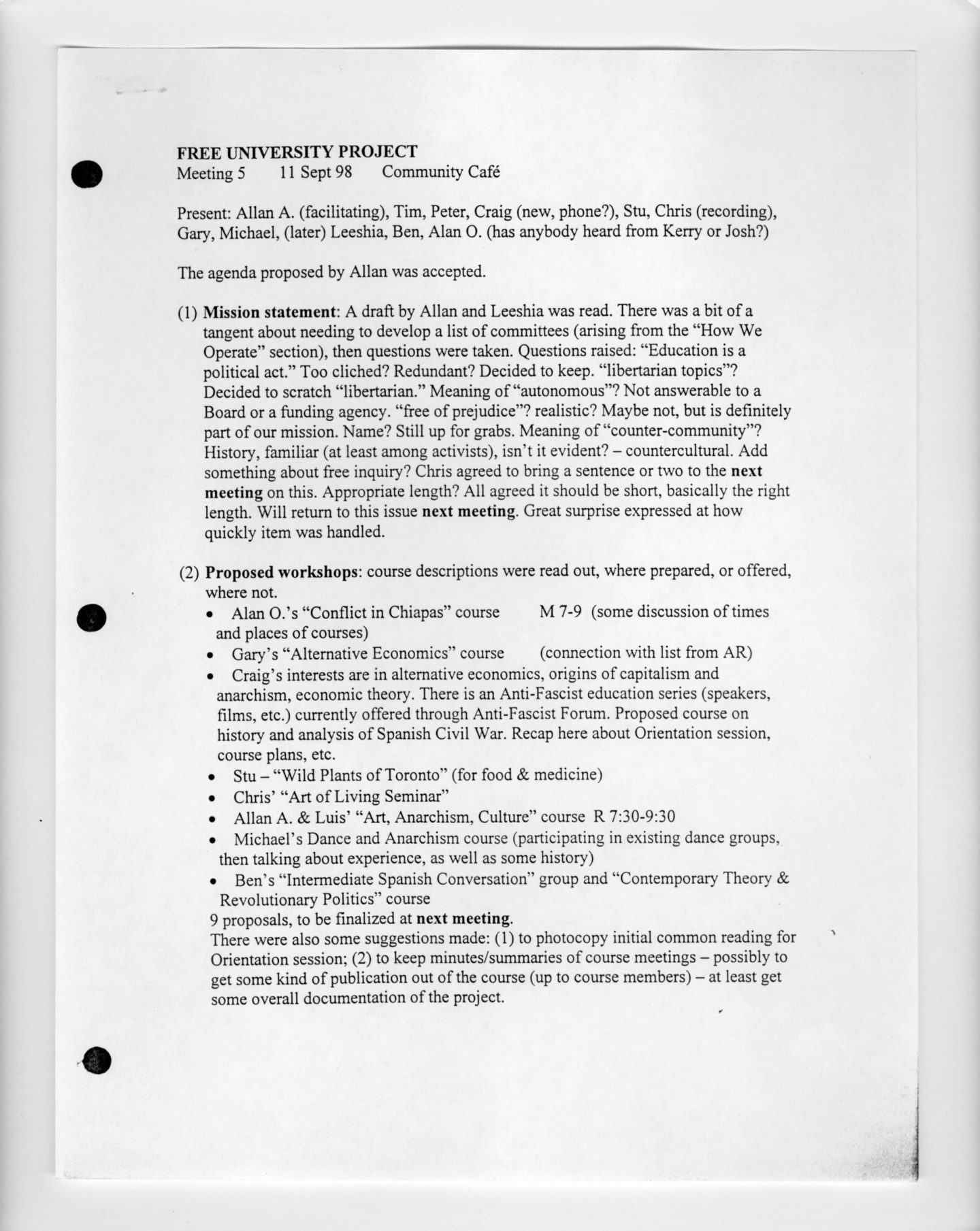

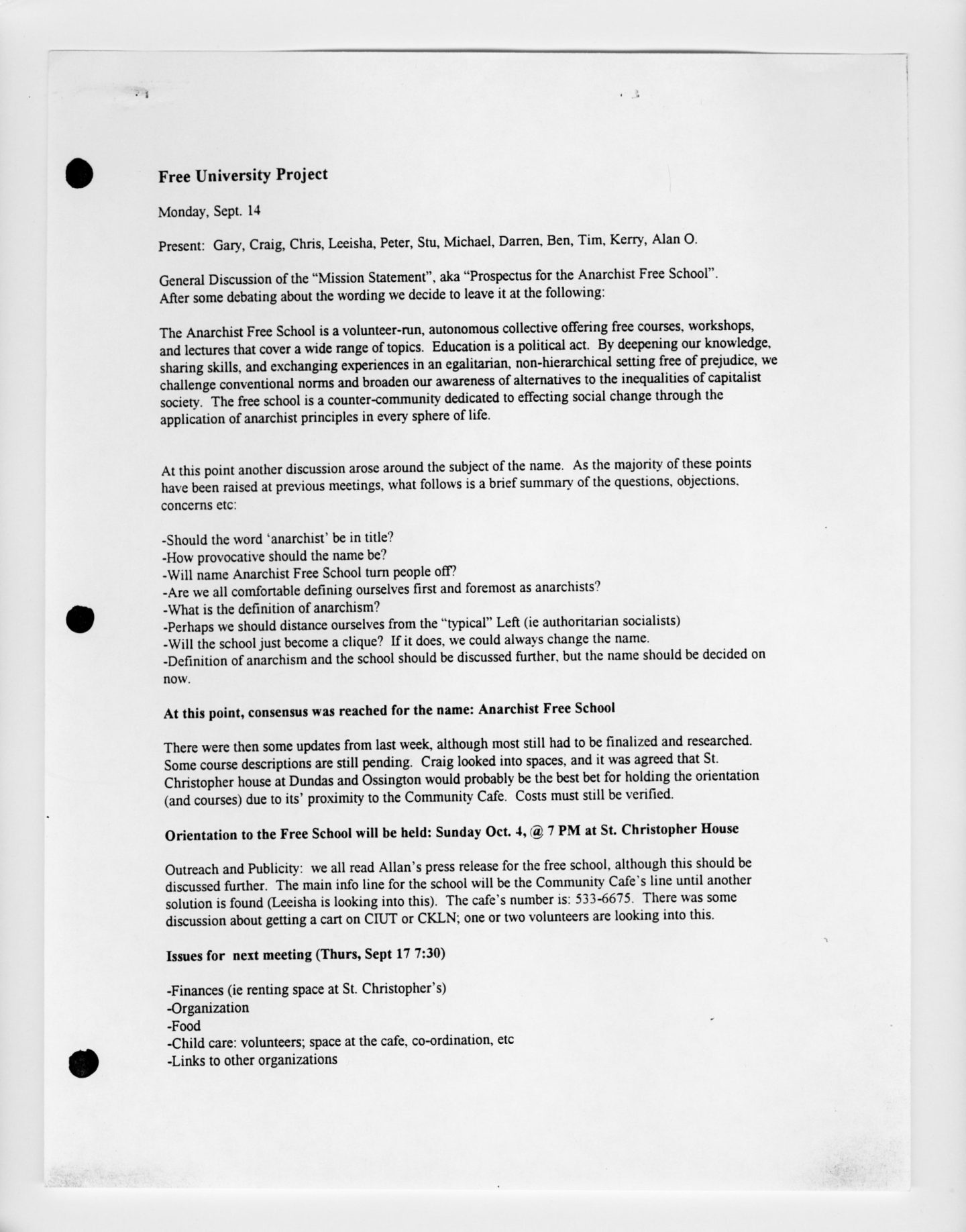

Jacob notes that the organizational principles of the Free School reflected an anarchist commitment to non-hierarchical structures and collective empowerment. The foundational idea, he explains, was that “everybody is a student, and everybody is a teacher.” This ethos created an environment where individuals could share knowledge based on their experiences and expertise, embodying an inclusive approach that resisted traditional power dynamics. The concept of a “commitment threshold” was introduced, wherein consistent participation in two to three meetings granted individuals decision-making power. This structure avoided any centralized ownership, allowing the group to make decisions collectively and ensuring that the school remained an open and adaptive space.

The Free School’s logistics mirrored its educational philosophy, operating as a self-organizing structure where members could propose and facilitate classes independently. As Jacob describes, the school functioned as “a model and counter-model” under which classes were proposed, coordinated and disseminated by anyone in the community. While initially hosted in a shared community basement space, the school eventually moved to a more permanent location on Augusta Avenue in Kensington Market, sustained by contributions from community members. This location, complete with a library and garden, became a vibrant cultural hub during its three years of operation.

The minutes play a crucial role in preserving the history and philosophy of the Anarchist Free School, and this act of preservation is where Jacob sees value in its archival existence. Jacob expresses a strong desire to see Anarchist Free School Minutes, 1999 contextualized in university gallery settings, saying, “it’s really important that it’s in a university gallery, in an art gallery collection, where students can encounter an anarchist approach to education, just to present a counter model, just so people have other visions of it.” This work, which began as a documentation of meetings and evolved into an installation piece, provides viewers with a tangible record of the anti-globalization and anti-colonial movements that formed the backdrop of anarchist organizing in Toronto.

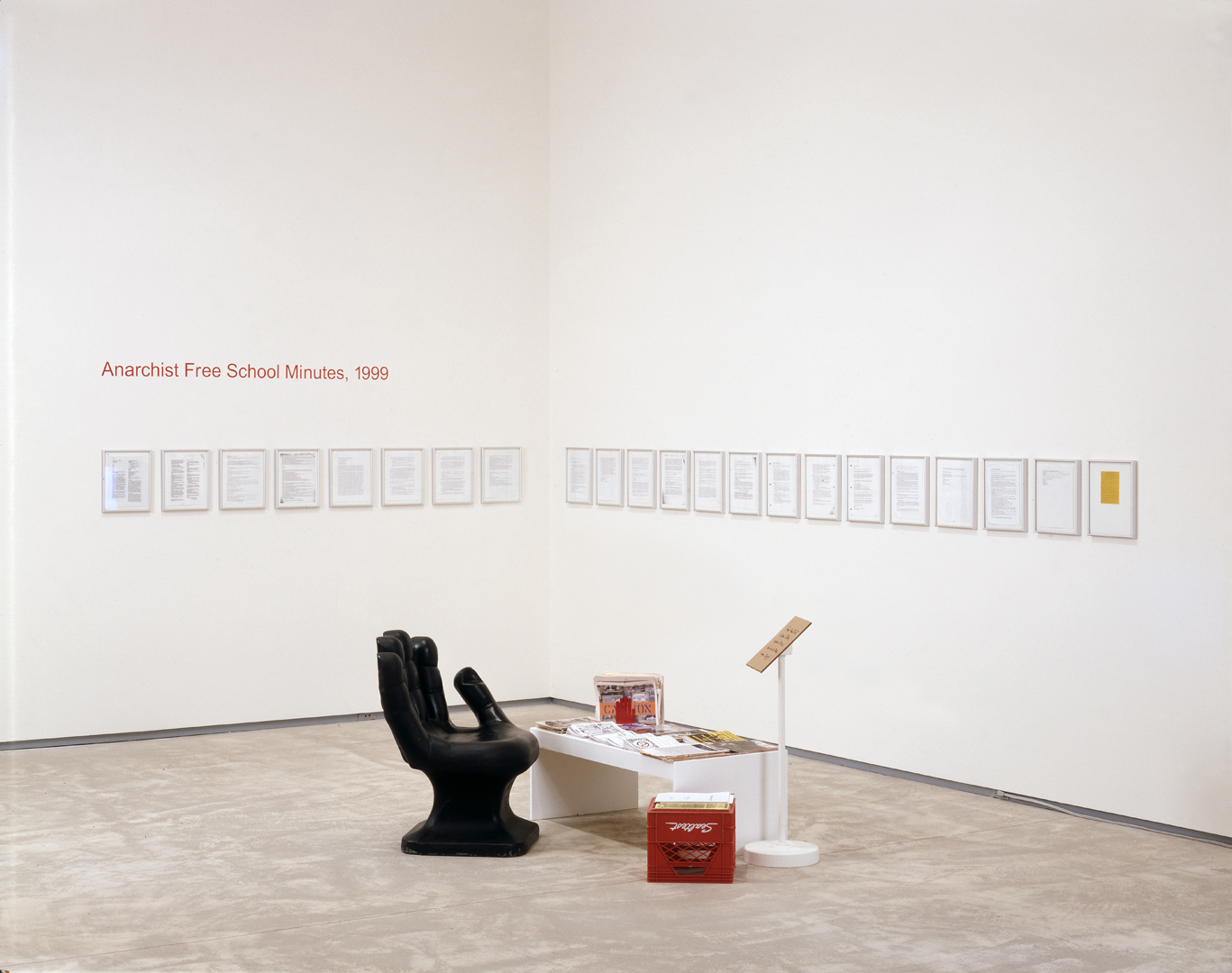

Luis Jacob, Anarchist Free School Minutes, 1999, 2002. Mixed-media on paper; plastic chair; vinyl lettering; anarchist literature and metal holder. Purchase, Canada Council for the Arts Acquisition Grants program and Agnes Etherington Art Centre Acquisition Endowment Fund, 2010

The Free School’s journey also intersects with broader historical shifts. Jacob recalls how the anti-globalization movement, a central influence on the Free School, rapidly lost momentum post-9/11. He observes, “this was all the anti-globalization activism, a global anti-colonial movement and that all died almost with a light switch, when 9/11 happened, because any activism can be called terrorism.” Jacob views the school’s legacy as an essential memorialization of the anti-globalization movement and its after effect.

Every time Jacob’s installation is exhibited, he works with the gallery to bring in zines, pamphlets and materials from contemporary activist movements, ensuring that the piece “always has a present dimension.” This interaction with the gallery reflects the anarchist spirit of the Free School itself, which remains adaptive, evolving with each new exhibition. Jacob emphasizes that the reading area in his installation keeps the memory of anarchist activism alive, acting as a bridge between past movements and the ever-changing present of current political climate. Jacob describes the installation as one that “opens itself up to indeterminacy. The indeterminacy is the anarchism of the piece itself,” urging the gallery to do the same—to embrace ongoing contextualization alongside contemporary political struggles. “For me the piece has two components,” Jacob explains, “which is the one collective coming into being and how that process happens, and the reading area brings it into the present, because every time its exhibited I ask the gallery to compile a collection of current activisms, [to get in touch with] anarchist info shops and purchase zines to populate the table, so that the collection keeps building every time its shown.” The Anarchist Free School decentralized pedagogical structures, inspired new modes of a collective decision-making process and initiated a commitment to knowledge-sharing that was a counterpoint to education in an institutionalized setting. Jacob’s reflections remind us that in spaces, such as the classroom or the gallery, can offer valuable insights into what pedagogy could look like if they were truly lateral and inclusive. Together, these resources offer future generations a blueprint for reimagining the possibilities inherent in the relation between pedagogy and community.

Reflecting on the importance of education within Anarchist Free School Minutes, 1999, Jacob articulates a personal journey rooted in the transformative potential of learning as a communal and emancipatory act. For Jacob, education in an anarchist context offers an alternative vision where learning is not a top-down transmission of knowledge but a process of mutual exploration. Even currently, this ethos continues to impact Jacob’s work. The zine, I am Full of Holes,3Made in collaboration between Luis Jacob and Rio Jacob. documents his migration from Peru to Canada and explores how this formative experience has shaped his understanding of community and education. Through his life story, Jacob’s work exemplifies how education, viewed through an anarchist lens, can help individuals grapple with diasporic identities and shared struggles.

The legacy of the Anarchist Free School endures through archival records, as part of Agnes’s collection, and active discussions on alternative education models—most recently highlighted in Only a Beginning: An Anarchist Anthology, edited by Alan Antliff (Arsenal Press). Jacob recalls how Alan O’Connor, who now teaches at Trent University, emphasized the importance of group moderation skills before launching the Anarchist Free School. O’Connor remarked, “if we’re going to run a free school, we’re going to have to figure out how to do group moderation, because that’s a key skill.” He subsequently led a workshop on anarchist group mediation, which Jacob attended and found transformative. The class taught consensus-building, reading group dynamics, handling dominant voices, and ensuring genuine agreement without tacit assumptions. These skills made a lasting impact on Jacob, who still uses them in his teaching today. He reflects on how O’Connor credited these techniques to “lesbians who were involved in the body politic,” specifically from a pre-AIDS era of queer and lesbian activism, emphasizing how O’Connor “was letting you know where that ethos comes from.” For Jacob, this pathway of learning—from queer activism to anarchist circles to university classrooms—illustrates what he sees as the “oral trajectories of a certain ethos” and embodies his understanding of education as a process of “ethos transmission” across generations and contexts.

The vision and intent of the Anarchist Free School resonate powerfully today, particularly in light of recent student encampments that erupted across university campuses in solidarity with Palestine and its liberation movement. These protests echo a shared commitment to challenging violent structures and imagining education as a space for political expression and resistance. They also prompt reflection on what Palestinian scholar Karma Nabulsi has termed scholasticide—the systematic erasure and destruction of Palestinian educational infrastructure under occupation—and the attempts to silence and penalize those who support the anti-occupation movement.4Sonia Bin Jaafar, “Scholasticide cannot be normalized,” in Al Jazeera, 6 September 2024, accessed 4 November 2024. For Jacob, the Anarchist Free School’s inherent indeterminacy continues to serve as a model for alternative forms of learning and teaching. It encourages the inclusion of contemporary ephemera and publications, such as zines, in the gallery’s reading area. This continuous renewal of activist and artistic materials keeps alive the idea of education as a radical, evolving process—one that adapts to each new generation’s struggles and calls for liberation,5We are reminded here of Noura Erekat’s writing on how nothing will be the same again, see: Noura Erakat, “Nothing Will Ever Be the Same Again,” in The Nation, 7 October 2024, accessed on 4 November 2024. where the “transmission of ethos” remains central to movement-building.