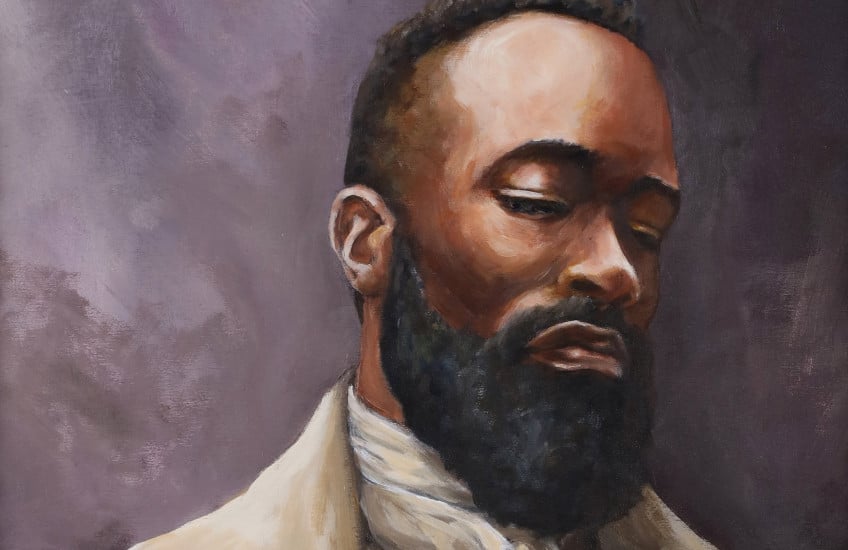

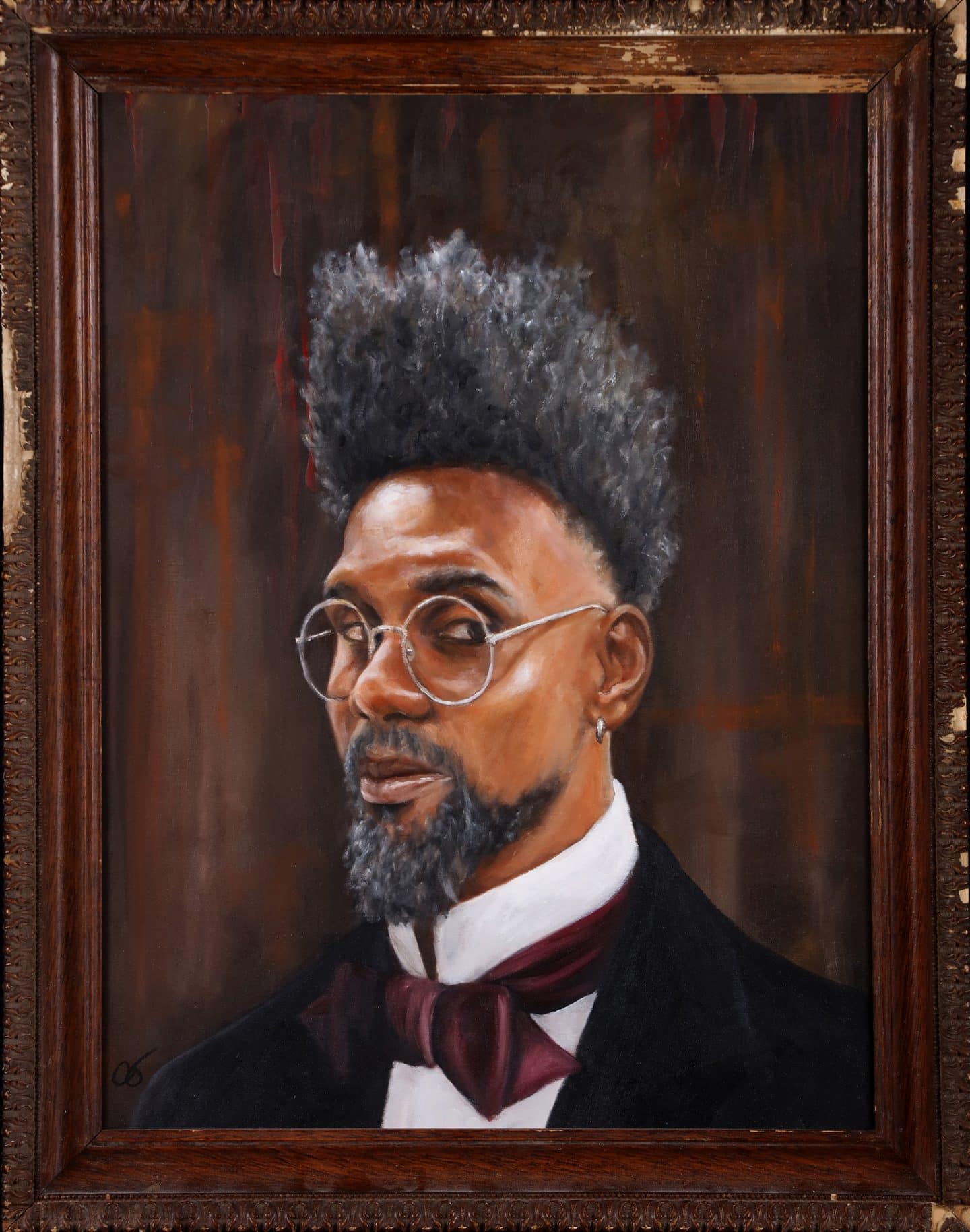

Gordon Shadrach, Written in Stone, 2017, acrylic on birch panel. Private collection. Photo: Bernard Clark

Since the public murder of George Floyd and the social justice uprisings of summer 2020, there has been a renewed call to challenge racism. We must question dominant narratives and reimagine an equitable history. Yet, how do we do this? What archives might we mine? What frameworks do we question?

History Is Rarely Black or White explores these questions through garments, artifacts, portraiture, and contemporary art related to the cotton trade. The capitalist structure of the 1700s to 1800s cotton supply chain systemically entrenched Blackness as an inhuman, economic element to be controlled.

This legacy is still with us today— manifesting in the ways people of colour are disproportionately policed and incarcerated. The 1800s cotton garments in the Queen’s Collection of Canadian Dress were created through the cotton trade that produced this problematic legacy. There is therefore a direct link between the cotton industry, Agnes’s collection of such garments, and Kingston’s penitentiaries.

We ask: what does it mean to be Black in Canada? How has life changed over time? How can we bring into being a different future?

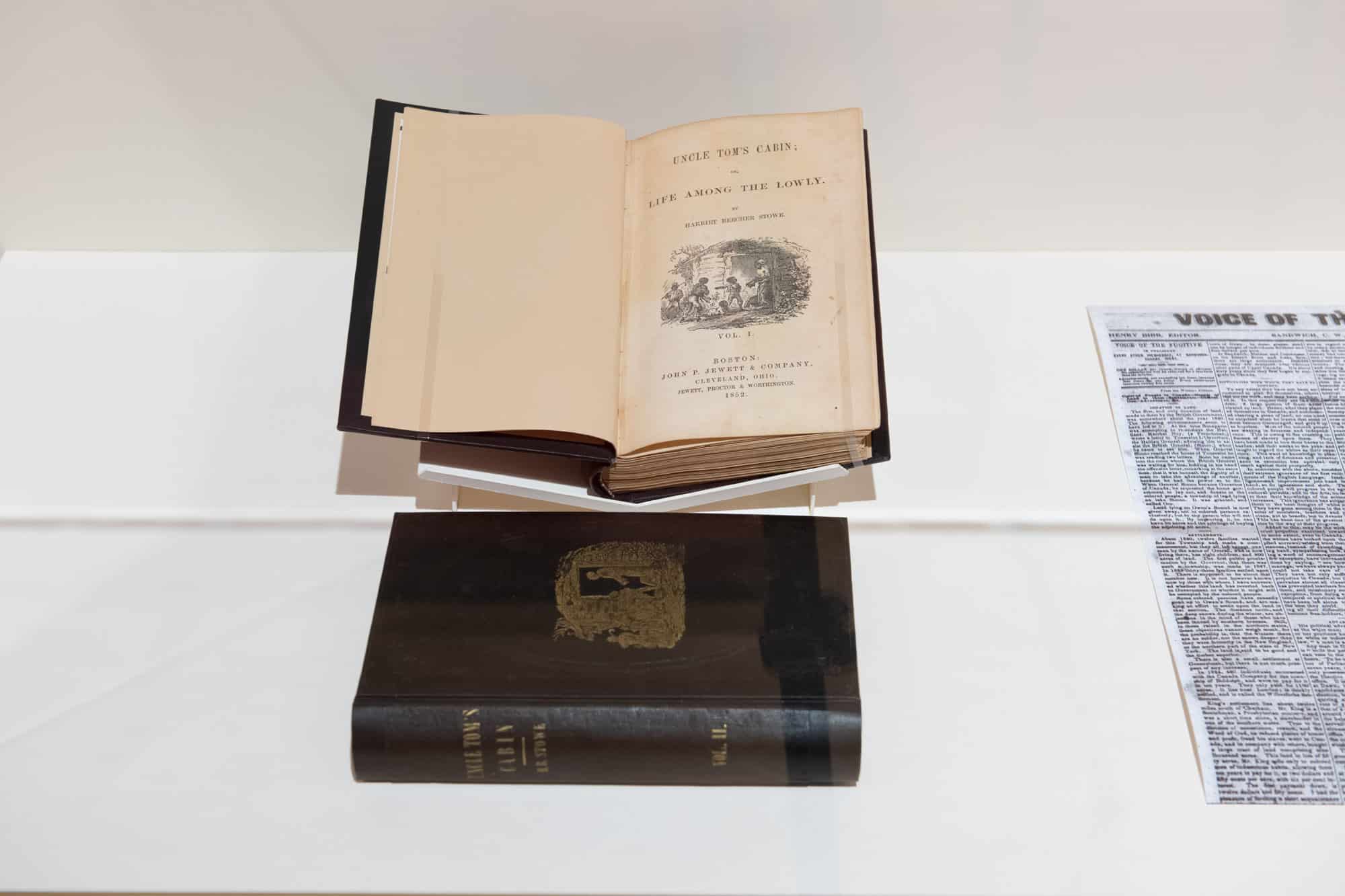

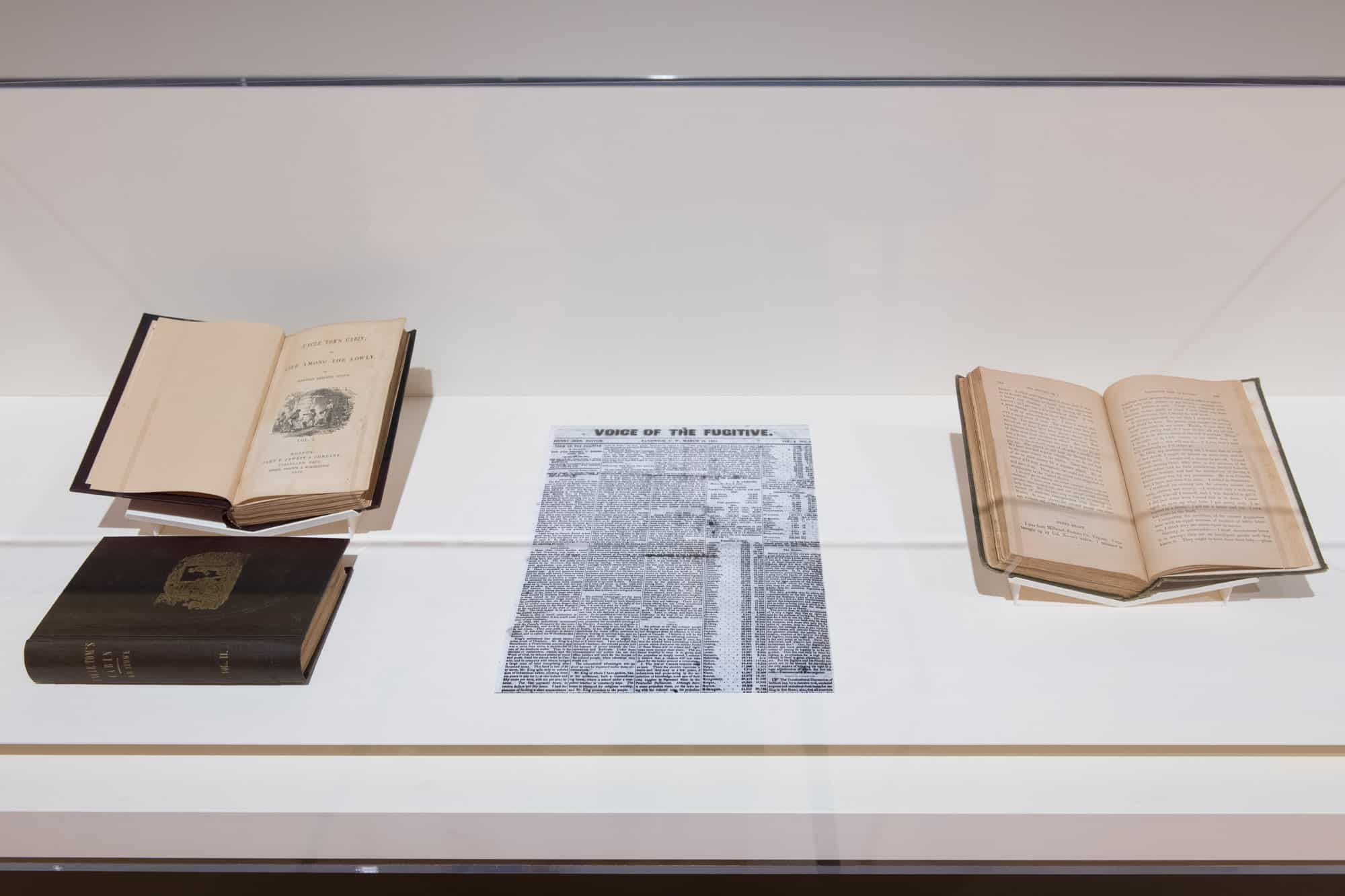

Illuminating this history are two volumes of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s book Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Stowe’s book helped to raise public awareness of slavery and was inspired by the life of Reverend Josiah Henson, who had been a slave for 41 years until he and his family escaped to Upper Canada via the Underground Railroad in 1830. The two volumes of Uncle Tom’s Cabin from the W.D. Jordan Rare Books and Special Collections, Queen’s University are first print editions that include errors and an original character whose name has since changed.

Benjamin Drew’s book, A North-side View of Slavery, details the narratives of fugitive enslaved people in Canada. The book is opened to the account of Henry Brant, who in 1834 escaped slavery in Virginia, USA, and settled in Sandwich. The adjacent page explains that while conditions here for people like Brant were different to American enslavement, their Canadian experience was rife with segregation and other racially fueled hardships.

(Left-Right): Portrait of Mary Jane McCurdy at 9 years old, daughter of Nasa and Permelia McCurdy, undated, mounted photograph. Archives of Ontario / Archives publiques de l’Ontario (I0026081)

Unidentified woman, 1875, tintype photograph. Archives of Ontario / Archives publiques de l’Ontario, Alvin D. McCurdy fonds (I0028818)

Randolph Burr, who used the surname Holten after leaving slavery (Alvin’s great-grandfather), undated, mounted photograph. Archives of Ontario / Archives publiques de l’Ontario (I0024778)

Horace Hawkins, around 1890s, Mounted photograph, Archives of Ontario / Archives publiques de l’Ontario (I0027805)

Unidentified woman, 1875, tintype photograph. Archives of Ontario / Archives publiques de l’Ontario, Alvin D. McCurdy fonds (I0028818)

Randolph Burr, who used the surname Holten after leaving slavery (Alvin’s great-grandfather), undated, mounted photograph. Archives of Ontario / Archives publiques de l’Ontario (I0024778)

Horace Hawkins, around 1890s, Mounted photograph, Archives of Ontario / Archives publiques de l’Ontario (I0027805)

Formerly enslaved African-Americans and their descendants living in Ontario used clothing and photography to present themselves as new Canadians with style, dignity and self-assurance. These individuals pushed back against their colonial identity as enslaved property – owned goods whose sole worth was to plant and harvest cotton. While these images are arresting in nature, the names of many people depicted therein are unknown. Similarly, the clothing of formerly enslaved individuals has been largely lost over time.

How might we mine existing archives to tell their stories?

The juxtaposition of the tintypes with related accounts from the Archives of Ontario, alongside similar garments from Agnes’s collection, form an ‘archival imaginary.’ This is curator Jason Cyrus’ term for the bringing together of related material across archives that contain records, textiles, clothing, photography, and oral history – which situated together fills gaps in institutional knowledge.

Pairing these items allows us to reimagine the stories and lives lost in archives.

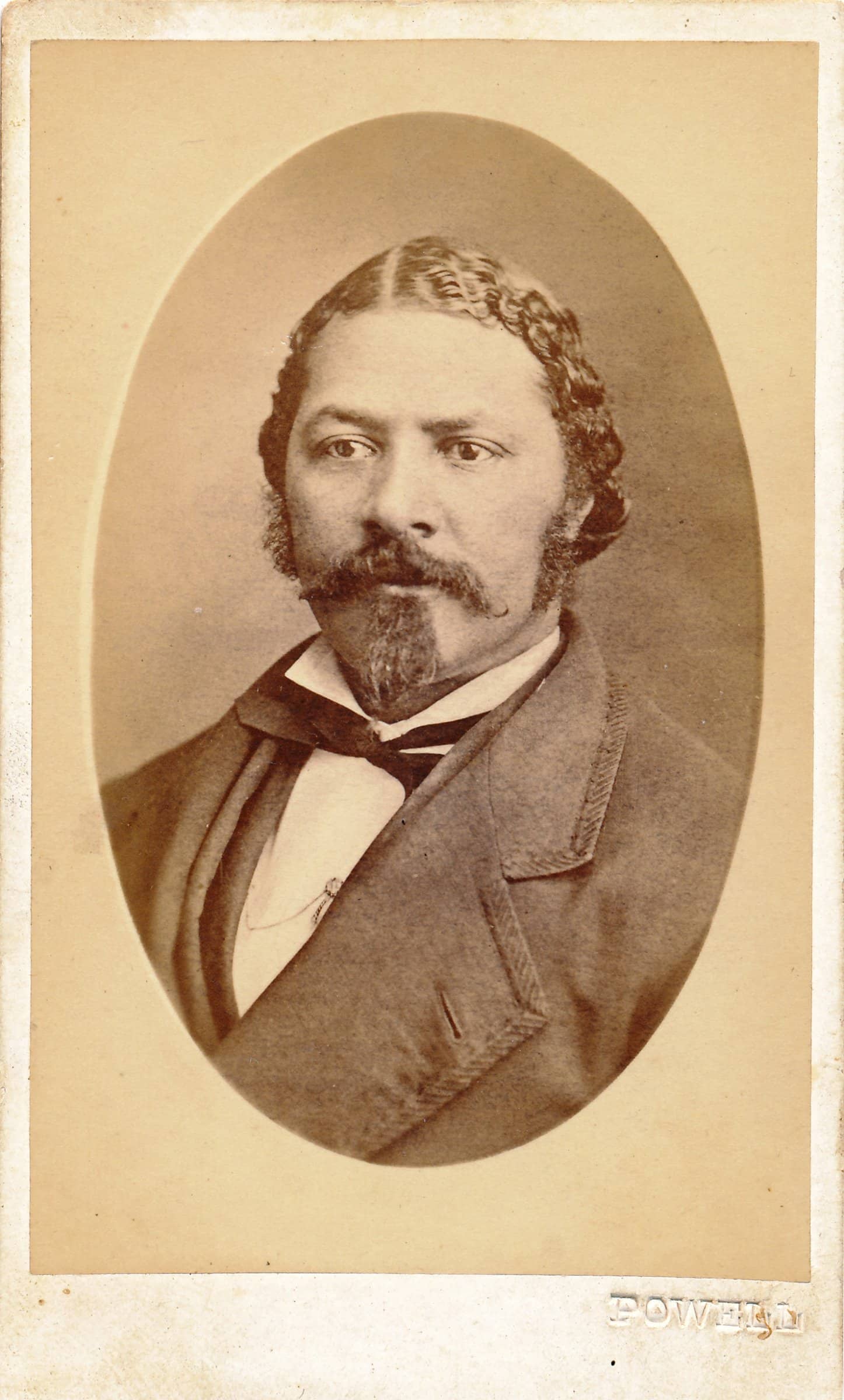

Jim Johnson, a Kingston barber, worked out of his salon on Wellington Street for forty years. The handwritten note on the reverse of this carte-de-visite indicates that Sir John A. Macdonald was a client.

Historian Jennifer McKendry shares that Johnson’s origin was noted as ‘African’ in the 1871 census, even though he was born in Ontario in 1837. His father William, also a barber, moved to Kingston in 1826 from Ohio during a time when enslavement, Blackness, and cotton were closely linked.

James Powell, Jim Johnson, around 1875, photograph. Collection of Jennifer McKendry

![The verso of a calling card with cursive handwriting on it. The card says, "Jim Johnson, Barber cut all [illegible] hair. Sir John "A" went to him."](https://agnes.queensu.ca/site/uploads/2021/11/Powell-James-Johnson-barber-back-coll.-J.McKendry.jpg)

James Powell, Jim Johnson (verso), around 1875, photograph. Collection of Jennifer McKendry

Installation view of History Is Rarely Black or White. Photo: Paul Litherland

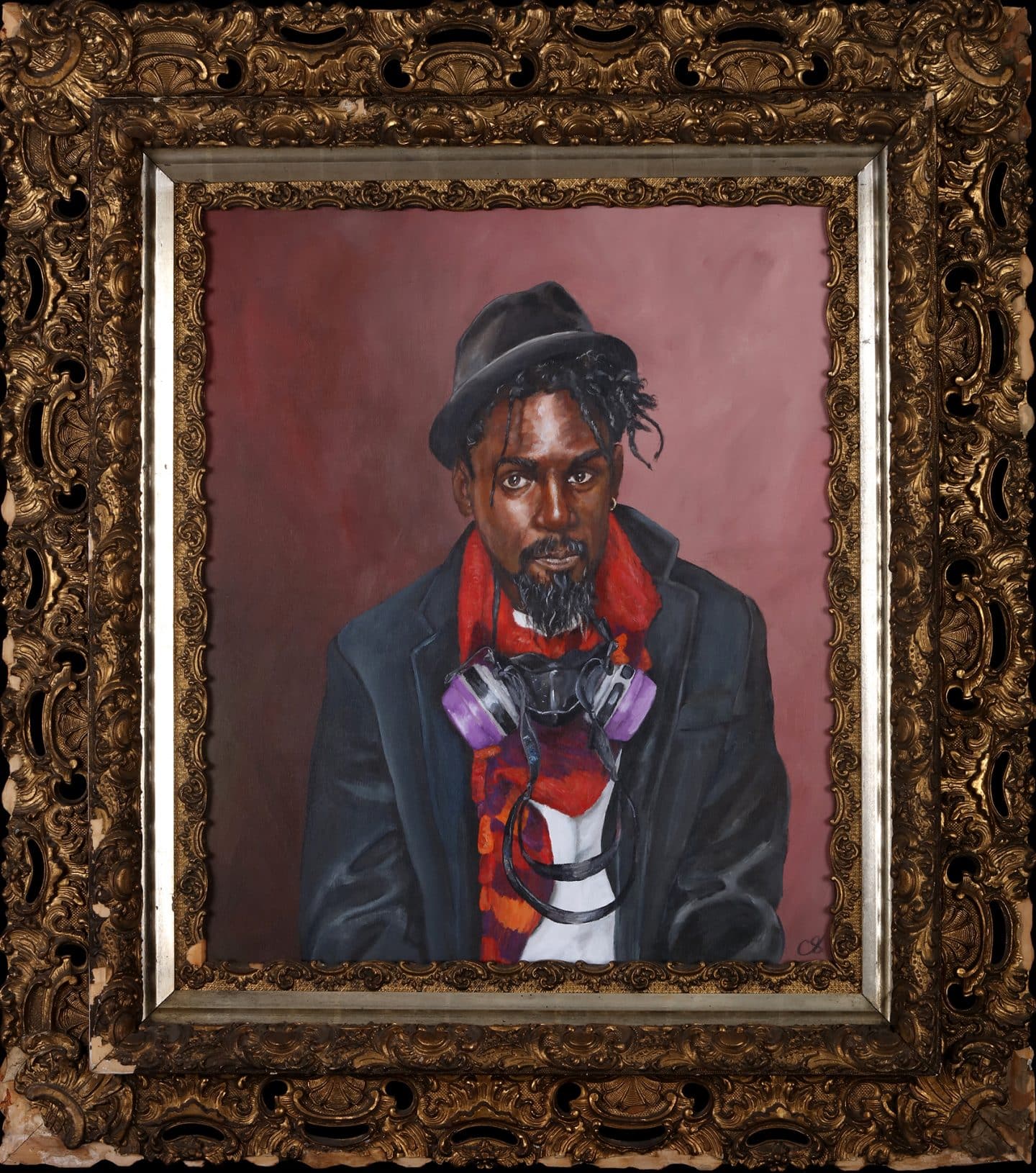

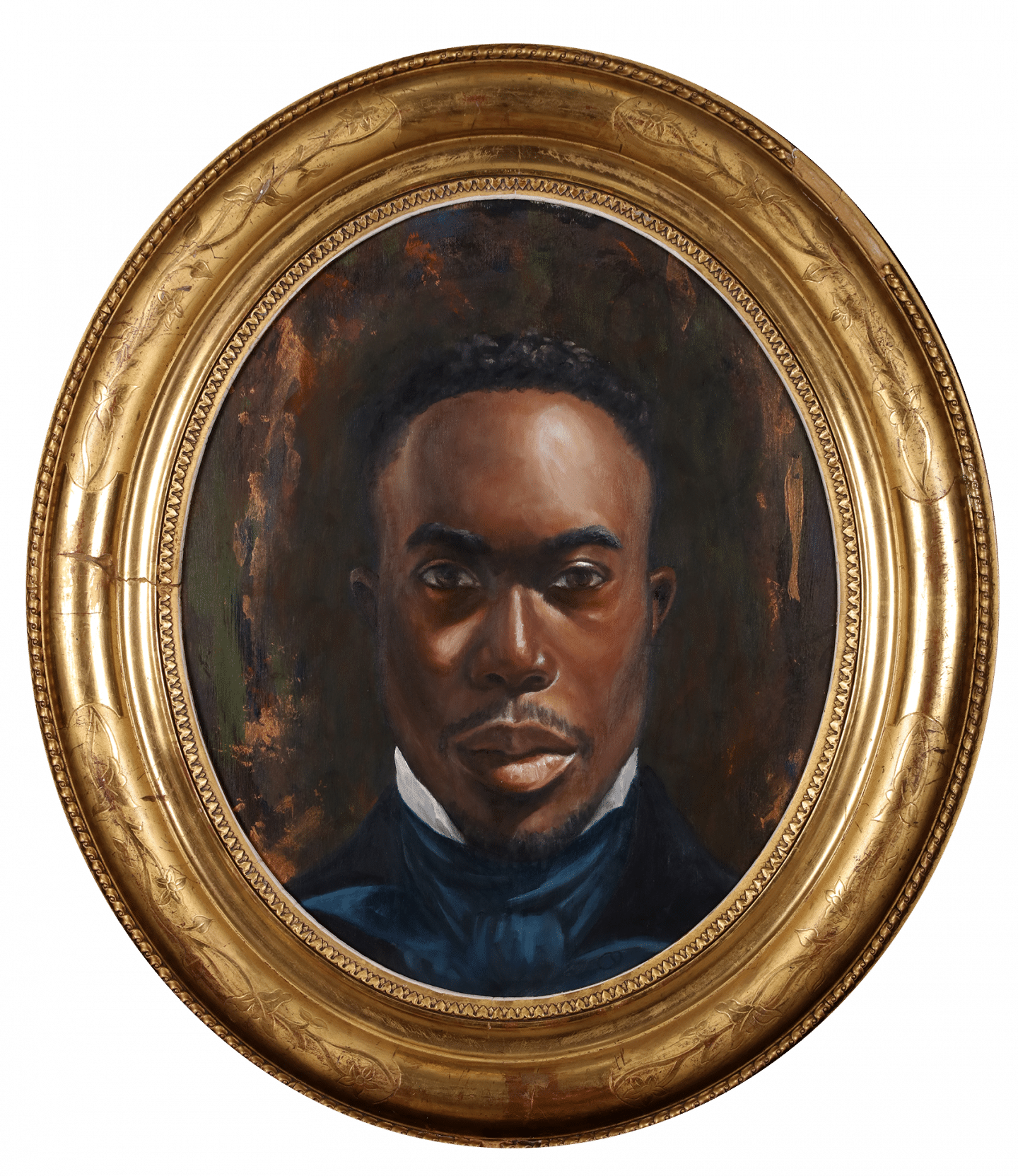

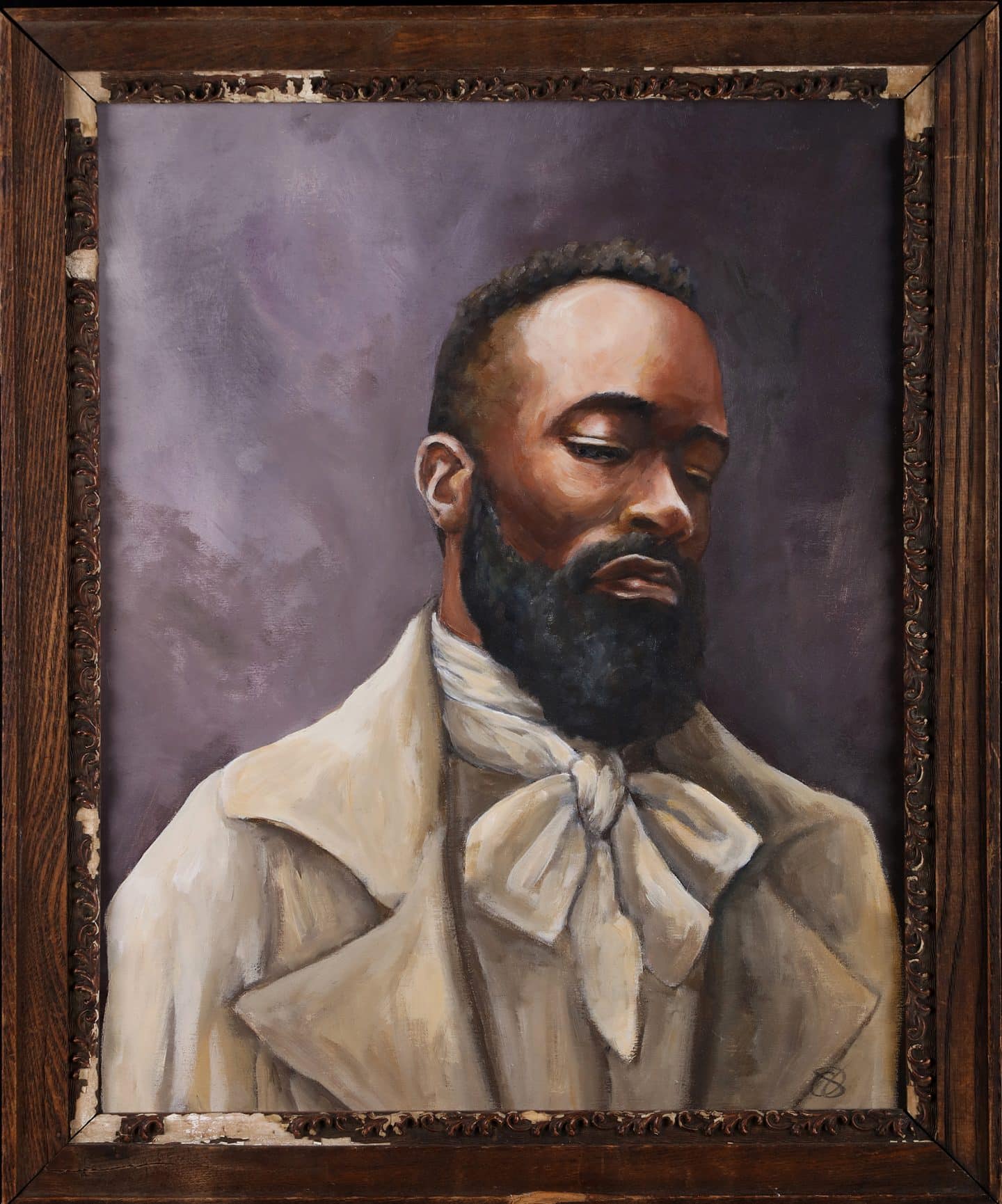

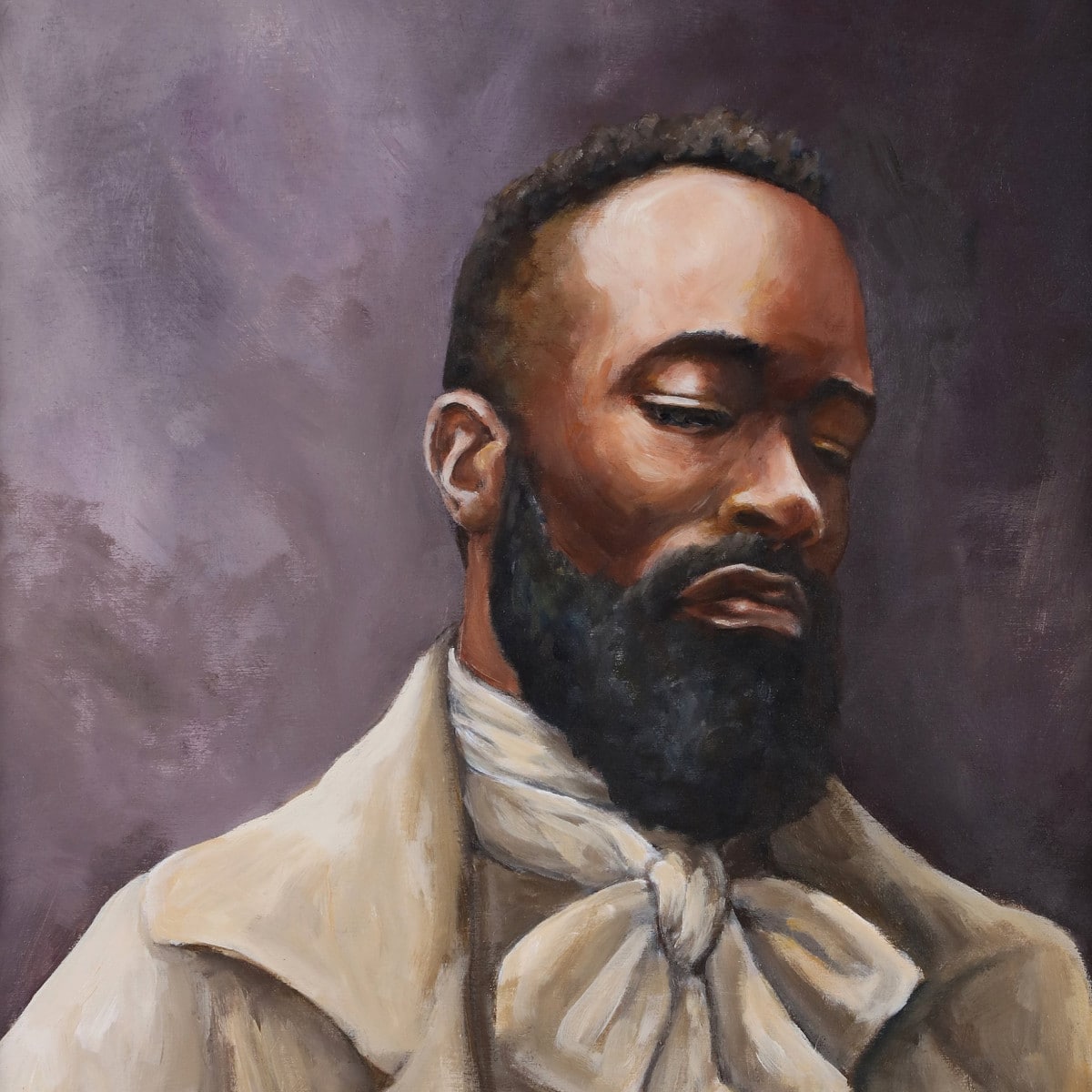

Gordon Shadrach’s work explores the cotton trade’s legacy of shaping perceptions of Blackness. In his portraits, Shadrach depicts men in historic and contemporary dress. He pays keen attention to his sitter’s hair, skin tone, clothing, and expression – aware of the ways in which these elements shift perceptions of their identity as either respectable or threatening.

In both Adorn and Procurement, Shadrach portrays artist Jabari “Elicser” Elliot. How do these portraits present Elliot differently? What negative or positive perceptions arise from their difference?

Video

Gordon Shadrach

Hear Gordon Shadrach speak about his paintings of Black men in historical dress.

Transcript

My name is Gordon Shadrach, and I’m a portrait artist from Toronto. My work speaks mostly about representation of Black males and confronting the stereotypes around how they’re presented, and also the semiotics of clothing. The series of portraits that are in this exhibit are reflective of the thread that runs through most of my work. In that it shows Black men in both contemporary and historical dress. It’s something that I’ve been fascinated with, by placing Black figures in a historical context where we were rarely seen. Both in historical art and in contemporary art. It was revolutionary to show Black people just existing in a piece of artwork without dealing with a political subject matter. However, Black bodies, in any context, whether they’re in a painting, or how their bodies are being used in sports, in work, or in labour, it’s always a political issue. And so one of the connecting factors that I think is really important to recognize, is that without Black bodies in North America, we wouldn’t have the structures that we have now. The structures that have now been designed to keep Black people out. So, essentially, we’re fighting to get our way back into something that we’ve worked for, and that’s something that we’ve earned.

When we look at a portrait like this one, where I’ve placed a contemporary Black man in historic dress, I’ve been confronted with viewers who feel that he looks like he’s wearing a costume. Despite the fact that Black people have existed for centuries and in North America for hundreds of years. There are people in the art world or in the audience that don’t recognize that we existed in certain historical eras. And so when confronted with issues — or, sorry, with pictures or images of Black people in historic dress, it confronts and it conflicts with their understanding of what North American or Western history is supposed to look like. So by inserting these Black bodies in these images, it really is quite challenging for a lot of people. And despite the fact that there are existing documentation, whether through painting or through tintypes and photographs, historical photographs, people are unaware of the existence of Black people in certain times in North America.