The Global Reach of Cotton

Installation view of History Is Rarely Black or White. Photo: Tim Forbes

The Queen’s Collection of Canadian Dress, held at Agnes Etherington Art Centre, comprises a fine example of rare garments from the 1700s to the 1990s. Exhibition curator Jason Cyrus, and conservator Anne-Marie Guérin, selected cotton clothing from the 1800s to investigate the influence of global politics and enslavement on the cotton industry. Although England officially abolished slavery in 1833, cotton produced by enslaved labour comprised much of fabric imports until the American Civil War from 1861-65. How did these events influence the labour source of cotton?

The garments displayed reflect a cross-section of social wealth, showcasing maternity clothes, an infant christening gown, childrenswear, wedding dresses, and menswear. All consumers across the gender and generational divide were implicated in the cotton trade.

Installation view of History Is Rarely Black or White. Photo: Paul Litherland

Installation view of History Is Rarely Black or White. Photo: Paul Litherland

The Global Reach of Cotton

Visualizing the Cotton Supply Chain

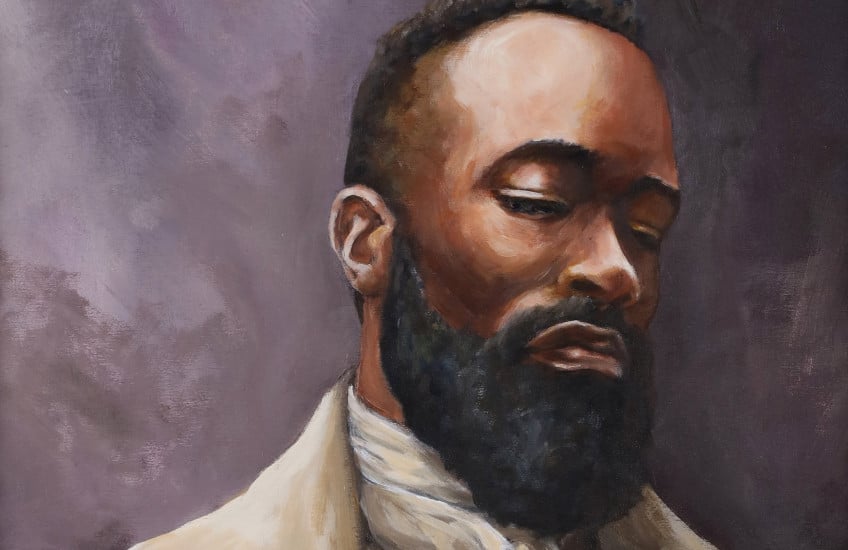

Artworks from Agnes’s European and Canadian Collections, and other archives, chart the people and places integral to the cotton trade in the 1700s to 1800s.

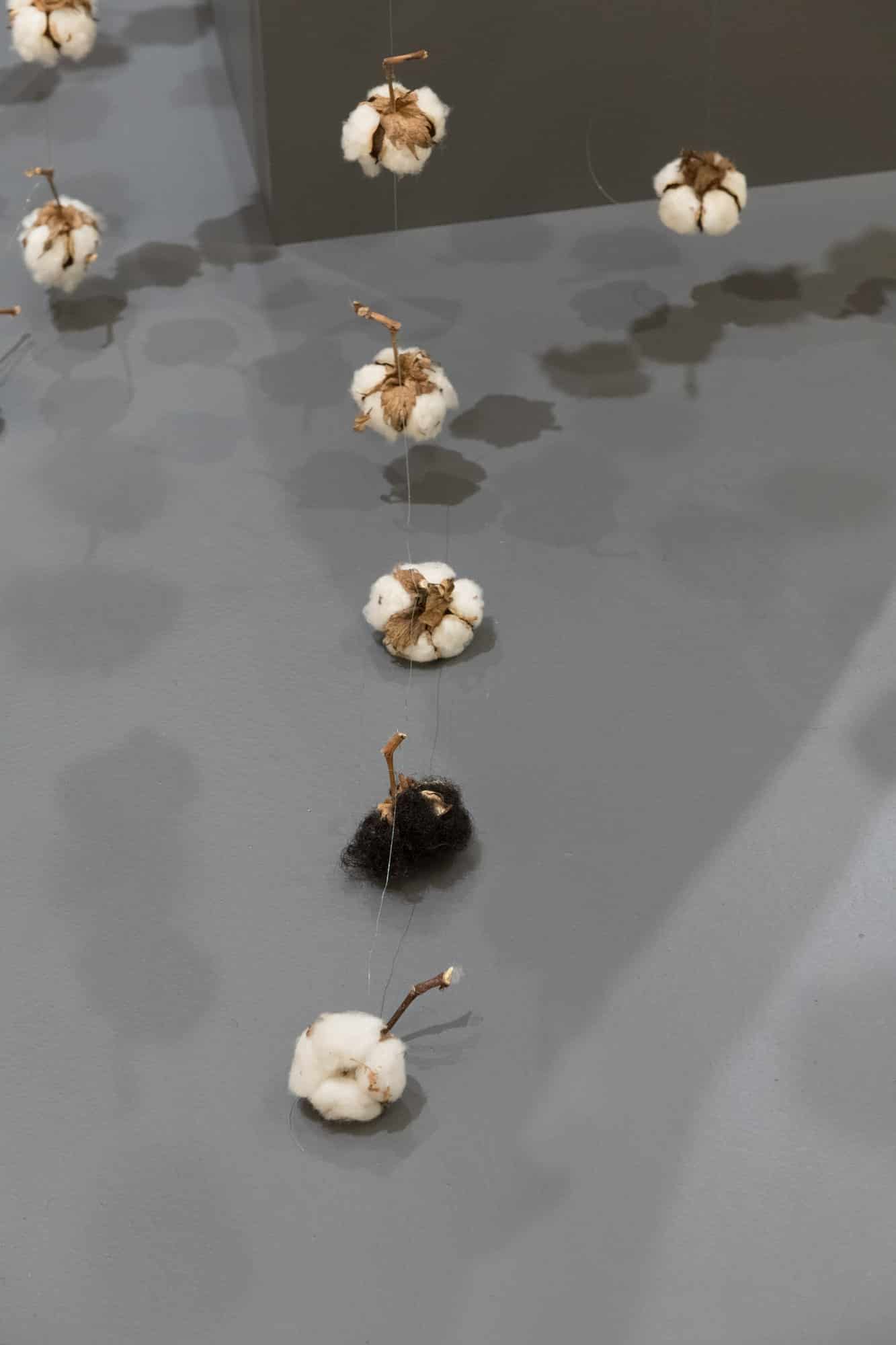

Karin Jones’s multi-disciplinary practice examines the ways in which historical narratives shape our identities. Freed, her site-specific installation, unites the materiality of Agnes’s cotton garments with their social and political history. Here, Jones places the labour integral to the cotton trade at the center of the narrative. Clouds of raw cotton and Black hair encircle the dress, forming a ‘remembering’ of the brutality, cultural erasure, and loss of life implicated in the creation of such garments.

Video

Karin Jones

Transcript

My name is Karin Jones. I’m an interdisciplinary artist with a background in jewellery and I’ve created this work for the exhibition at the Agnes. So, my work in recent years has mostly been about the way that historical narratives shape our identities. And as a woman of African descent, a lot of this has been attached to the history of slavery. So, for this piece, I really was thinking about how that narrative of slavery is the really predominant story that gets told about black people in North America. And it’s a much stronger narrative that’s presented to us than, say, even the histories and cultures of the actual African countries that our ancestors would have been taken from. So, in a way, this story of slavery, and specifically about cotton fields, which gets used in so many countless movies and books becomes almost like an origin story of where we’re coming from. So, for this piece, I have natural cotton balls, and some of them, I’ve removed the cotton from the husk and glued in different people’s hair, so hair from black people in North America, just to show that, in a way, we’re growing out of those cotton fields. And for this piece, I also wanted it to be, these balls to be hanging, because it’s meant to be shown with historic garments, so that when we look at garments in a museum, we literally can’t look at the garment itself without also being confronted with this history.

Karin Jones, Freed, 2021, cotton, hair, wire, and wood. Collection of the artist. Photo: Paul Litherland

A detail of Karin Jones’s site-specific installation, Freed, showing the bulbs of raw cotton and Black hair. Photo: Paul Litherland

Installation view of History Is Rarely Black or White with a view through the doorway to the exhibition With Opened Mouths. Photo: Paul Litherland