An old grey beard is leaving Kingston, Ont., for Edmonton and Regina this year. Prepare to be awed.

Head of an Old Man in a Cap was painted in 1630 by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-69) when the Dutch master was just 24 and still working in his hometown of Leiden. It’s one of the gems in the nationally touring exhibition Leiden circa 1630: Rembrandt Emerges, organized last year by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre in Kingston to mark the 350th anniversary of Rembrandt’s death.

“It is around the year 1630 that Rembrandt fully launches himself, unleashing his full potential as a confident, capable and innovative artist,” curator Jacquelyn N. Coutré writes in the exhibition catalogue. “This is demonstrated supremely by his Head of an Old Man in a Cap, in which he masters the rendering of the human face on a life-size scale.”

The painting’s detail is astonishing. Look closely and you can count the hairs on the old man’s eyebrows. He is a stock character, or tronie in Rembrandt’s parlance. Rembrandt created tronies to carve out a market different from the official portraits painted by Leiden’s more established artists.

The painting was acquired by the late businessman and philanthropist Alfred Bader in 1979 at auction and donated to the Agnes Etherington Centre, at Queen’s University, in 2003. Bader, who died in 2018, escaped the Nazis in Vienna as a child, came to Canada, studied chemistry at Queen’s and became a hugely successful businessman in Milwaukee. His generosity allowed the Agnes Etherington to amass Canada’s largest collection of Rembrandt paintings and prints.

This travelling exhibition, limited to Rembrandt’s early years in Leiden before he relocated permanently to Amsterdam, contains many borrowed works, along with some of the Kingston treasures. It will be on view at the Art Gallery of Alberta in Edmonton from March 7 to June 14 and at the MacKenzie Art Gallery in Regina starting next August.

At times, the exhibition seems as much about another artist, Jan Lievens, as about Rembrandt. The two were contemporaries in Leiden. They were friends who used the same models, sometimes modelled for each other, tackled similar themes and copied one another’s prints. But they were also rivals, pushing one another to experiment and improve. Compare their works in the exhibition and decide who was better.

Among the paintings and prints by Lievens is the showstopper, A Man Singing, painted around 1624. It portrays an old, bald man.

“His open mouth and right hand raised in an act of time-keeping suggest that he is singing,” the catalogue notes. “He gazes away from the viewer, possibly toward another singer or a musician outside of the picture frame. Boldly illuminated from the left, his large form casts a shadow against the plain background. His physical presence is overpowering, from his bulbous neck to his vein-ridden pate.”

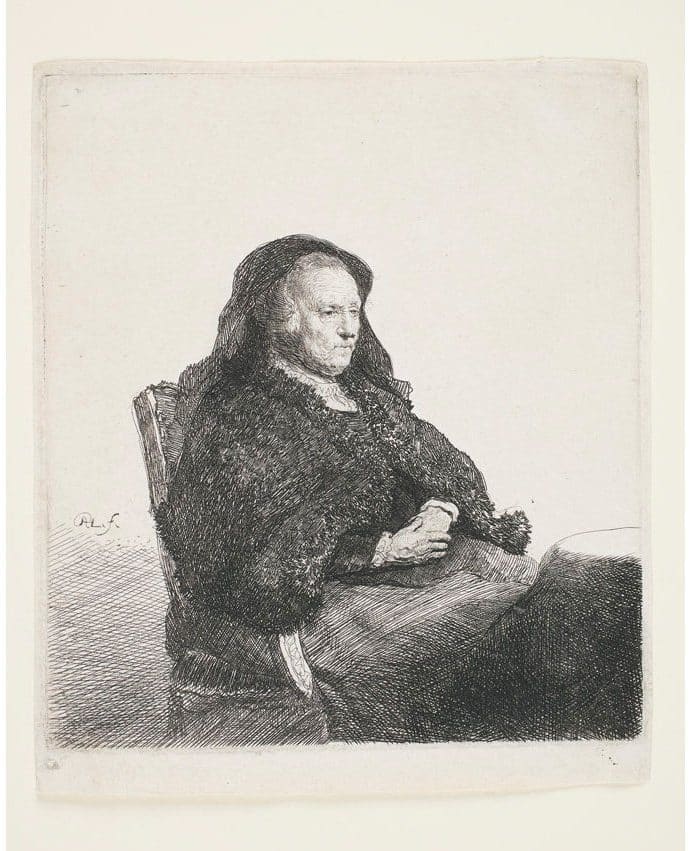

Rembrandt and Lievens both favoured painting and etching old faces during their early careers in Leiden. Several works in the exhibition are labelled as Rembrandt’s father or mother. It’s likely not all these seniors are Rembrandt’s parents. There’s even speculation that one of Rembrandt’s favourite “mother” models was actually Lievens’ grandmother.

Rembrandt created many self-portraits, mainly etchings, in this period. Not all are making the trek west from Kingston. Most noticeably absent is a remarkable painting that shows a surprised-looking, open-mouthed Rembrandt, aged about 23. Self-Portrait, circa 1629, was on loan only to Kingston from the Indianapolis Museum of Art.

But there are other ways to create self-portraits. Check the faces of young men in some of Rembrandt’s etchings. His face periodically appears like an Alfred Hitchcock cameo in his own movies. Who knew a total Rembrandt lookalike helped lower Christ’s dead body from the cross?

In the etching Beggar Seated on a Bank, 1630, Rembrandt takes a starring, albeit anonymous, role. The hump-backed beggar has the same shaggy hair, bulbous nose and wide mouth as the artist. (The etching will be in Regina, but not Edmonton). Placing his visage in his art was something of a marketing tool for Rembrandt.

The fragility of some works and the unwillingness of various institutions to part with treasures for lengthy periods means the exhibition is slightly smaller in the west than when it was first shown last year in Kingston.

Missing is the National Gallery of Canada’s Rembrandt, Heroine from the Old Testament. This delightful painting, known by various names, was completed in 1632-33 and would have fit nicely with the show’s theme. Alas, the painting did not make the two-hour drive from Ottawa to Kingston, despite being featured prominently in the exhibition catalogue.

The painting, which shows a plump young woman primping, presumably for some fancy occasion, will join other masterpieces once owned by the Prince of Liechtenstein and sold after the Second World War to various countries to replenish the principality’s treasury. The exhibition, The Princely Collections, Liechtenstein: Five Centuries of European Painting and Sculpture, will be on view at the National Gallery from June 5 to Sept. 7.

But don’t fret. There’s still art aplenty heading west from Kingston to educate and entertain Rembrandt fans. His mothers, fathers, self-portraits and Biblical scenes do not come this way often. ?

Leiden circa 1930: Rembrandt Emerges is on view at the Art Gallery of Alberta in Edmonton from March 7 to June 14, 2020 and at the MacKenzie Art Gallery in Regina from Aug. 22, 2020 to Jan. 3, 2021.

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Artist’s Mother Seated at a Table, Looking Right: Three-Quarter Length, circa 1631, etching on paper, sheet (irregular) 6″ x 5″. Collection of Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto; gift of Esther and Sam Sarick, 2006

Jan Lievens, A Man Singing, around 1624, oil on panel. Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont. gift of Alfred and Isabel Bader, 1991

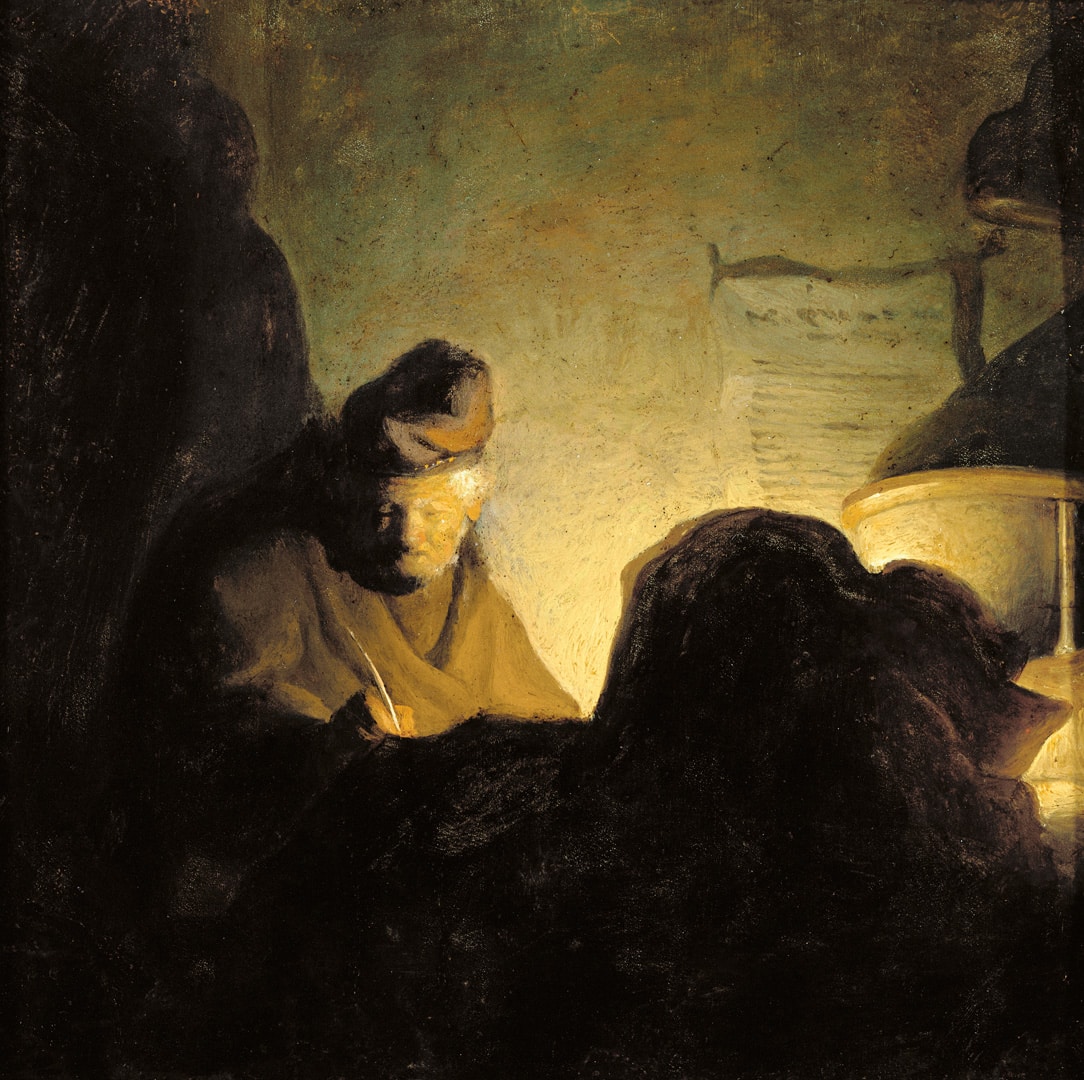

Attributed to Rembrandt van Rijn, A Scholar by Candlelight, 1628–1629, oil on copper. Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen’s University, Kingston. Gift of Isabel Bader, 2019