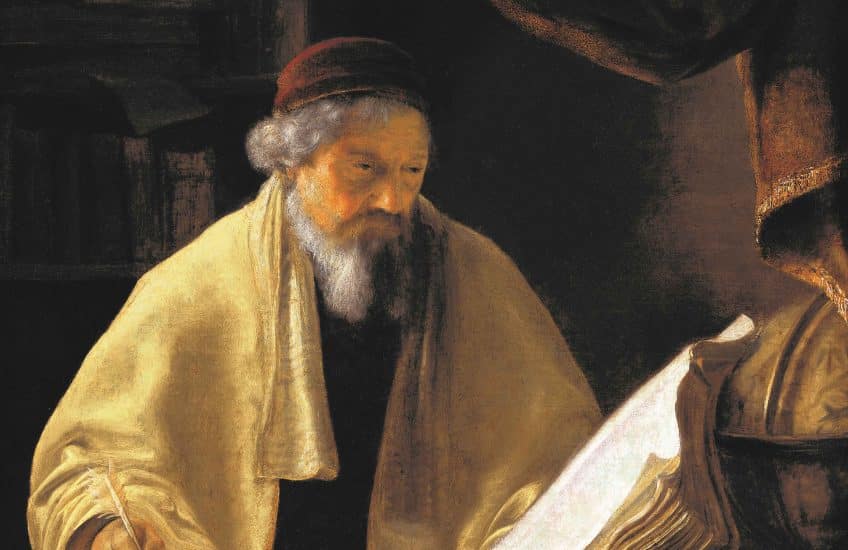

Immerse yourself in Godfrey Kneller’s

A Scholar in His Study (about 1668) featured in

From Tudor to Hanover: British Portraits, 1590-1800. Listen to four informed perspectives on the painting, including:

- Dr Maxime Valsamas, Curatorial Assistant, European Art

- Dr Stephanie Dickey, Professor and Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art, Department of Art History and Art Conservation, Queen’s University

- Dr Daniel Woolf, Principal Emeritus and Professor, Department of History, Queen’s University

- Natasa Krsmanovic, Conservator, Rare Books and Special Collections, University Archives, Queen’s University