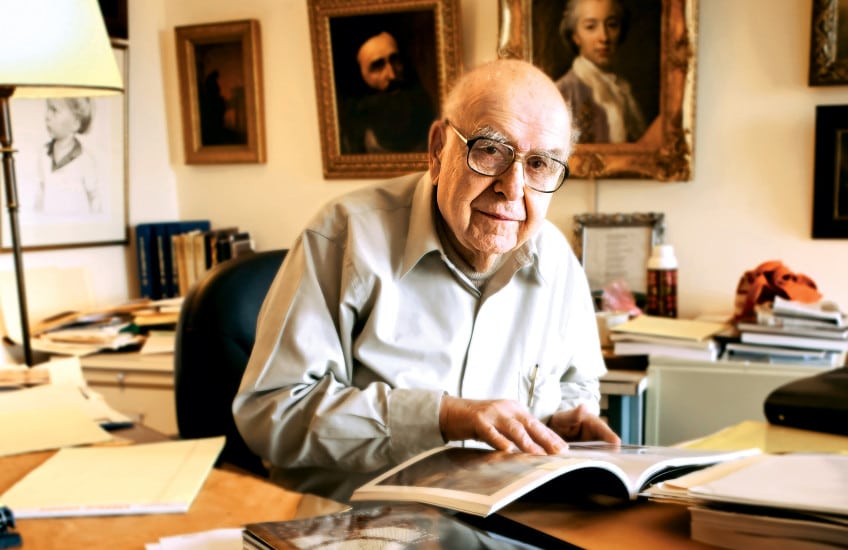

Lovingly brought together over a span of nearly seven decades, The Bader Collection owes much to the values and discerning eye of its chief composer, Dr Alfred Bader (1924–2018).

Today The Bader Collection encompasses more than five hundred works of art, including close to three hundred paintings. The first gifts were presented to Agnes in the late 1960s and early 1970s by Bader and his first wife, Helen (Danny) Bader (née Daniels) (1927–1989). These early gifts consisted of various European paintings, including Italian works of art. Notable works of primarily Dutch seventeenth-century art, which quickly became the focus of Bader’s collecting interests, were gifted in subsequent decades by Alfred and his second wife, Isabel Bader (née Overton) (1926–2022). These would include four works by the celebrated Dutch painter Rembrandt van Rijn, one of which was presented by Alfred’s son Daniel Bader and his wife Linda (née Callif) in 2019. These remarkable acts of giving were continued only recently with a bequest of artworks from Isabel’s estate.

At the time of writing, we are eagerly anticipating the reopening of Agnes in a new facility, which was made possible by the generosity of Bader Philanthropies Inc. We also look forward to the realization of Alfred’s full vision for his collection, which aims to unite all the paintings he and Isabel amassed with the goal of gifting them to Queen’s University in Kingston. The great majority of these works have previously been described by Dr David de Witt, Bader Curator of European Art at Agnes from 2001 to 2014 in his two collection catalogues, The Bader Collection: Dutch and Flemish Paintings (2008) and The Bader Collection: European Paintings (2014). Only the small number of works that were acquired after the publication of the latter volume have escaped his careful and considerate analysis. These more recent acquisitions, including the spectacular Man with Arms Akimbo by Rembrandt van Rijn (Gift of Alfred and Isabel Bader, 2015), were overseen by De Witt’s successor, Dr Jacquelyn Coutré, Bader Curator between 2015 and 2019. Coutré also spearheaded digital initiatives surrounding the collection, which have enabled both the development of digital publication and the collection’s enhanced presentation on our online collections website. It will be through these digital infrastructures that key information and changing scholarship on its paintings will be shared with audiences, now and in the future.

At this pivotal moment, it is only fitting that both past and current stewards of The Bader Collection take a moment to reflect on its significance—both to its original composer, Alfred Bader, and to the institution that has been, and continues to be, transformed by its presence. The exceptional quality of The Bader Collection has steadily marked Agnes and Queen’s University as a leading center for innovative research and curation of historic European Art, the art of Rembrandt van Rijn and his circle in particular. In his essay, Dr David de Witt considers the special relationship between Alfred Bader and this Dutch old master, one informed in part by Bader’s early teachings by the art historian Jakob Rosenberg (1893–1980) and their shared cultural heritage as Jewish immigrants in post-World War Two America. As De Witt keenly notes, Bader’s extraordinary life story fundamentally shaped his artistic and collecting interests.

Alfred Bader was born in Vienna in 1924 to a Hungarian Catholic mother and Czech Jewish father. The latter’s early and unexpected death, however, led him to be raised primarily by his father’s sister in the Jewish faith. This important maternal figure, Gisela Reich (née Bader), had a foundational impact on the young Bader and was an important early model of the remarkable generosity he would come to embody during his own life. In 1938, the young Bader had to leave his childhood home to be sent on the first voyage of the so-called Kindertransport, arranged to send Jewish children from Nazi Germany to England. His refuge there did not last long, however. In 1940, at age sixteen, he was arrested and shipped out of Britain as a prisoner of war—along with all other German refugees deemed of age—and was interned at Île-aux-Noix in southern Quebec, Canada. It was not until November 1941 that he was allowed to leave the camp with sponsorship of the family of Martin Wolff (1881–1948), a relative of the family who had previously fostered him in England. Two universities that enforced strict quotas for the admittance of Jewish students denied his application before he was accepted at Queen’s University. Having found a welcoming academic community, Alfred Bader quickly thrived—the education he received in Kingston formed the starting point for his successful career in chemistry, as well as a lasting relationship with the university that opened its doors to him when others would not.

In her essay, Dr Jacquelyn Coutré describes the impact that Bader’s gifts had on historical European exhibition programming at his beloved alma mater, while contextualizing earlier institutional history with regard to this collection’s focus at Agnes. The construction of a dedicated gallery for presentation of The Bader Collection, as part of the Agnes’s expansion between 1998 and 2000, and the appointment of the first Bader Curator one year later, ushered in a new era of specialized curatorial inquiry into the collection. Coutré highlights the format of the temporary exhibition—still the preferred vehicle for engagement with this collection—for particular analysis, featuring its versatility and ability to respond to the changing needs of contemporary audiences.

In the final essay, Dr Suzanne van de Meerendonk, the current Bader Curator of European Art at Agnes, considers how the unique legacy of Alfred Bader, so thoughtfully described in the preceding essays, could inform work with The Bader Collection in the context of Agnes Reimagined. Taking Bader’s own writings as a departure point, van de Meerendonk posits that the collection’s distinct emphasis on human connection and moral responsibility allows for its engagement in curatorial projects that are both socially conscious and “neighbourly” in their motivation and design.