Bruce Kauffman, local poet and Agnes Receptionist speaks with Ezi Odozor about her poem Spirit Banter, her writing practice and what inspires her.

Originally recorded as part of Agnes’s docent training program. Excerpts from the transcript are included below. They have been edited for clarity. A full transcript is available with the audio.

Help Listening

Play Online

- Use the links on this page to choose which track you would like to listen to

- Press the “Play” button to begin

Listen In-Gallery

- Visit agnes.queensu.ca/digital-agnes

- Select the audio track you would like to listen to and press “Play”

Listening to this content will require a Wi-Fi connection or a data plan.

Some charges may apply, please consult your mobile provider)

Other Ways to Listen

Tap or click on “Transcript” under each track to read or download the full transcript of each audio commentary.

Transcript

Bruce Kauffman: Well, it’s nice to meet you, Ezi.

Ezi Odozor: It’s nice to meet you as well.

Bruce Kauffman: And you’re from Toronto.

Ezi Odozor: I am from Toronto. I was born in Nigeria, but I grew up in Toronto in Mississauga.

Bruce Kauffman: Very cool. Maybe we’ll talk about the exhibition first. The title of the exhibition is Spirit Banter. Could you provide two or three key overview points that introduce your work?

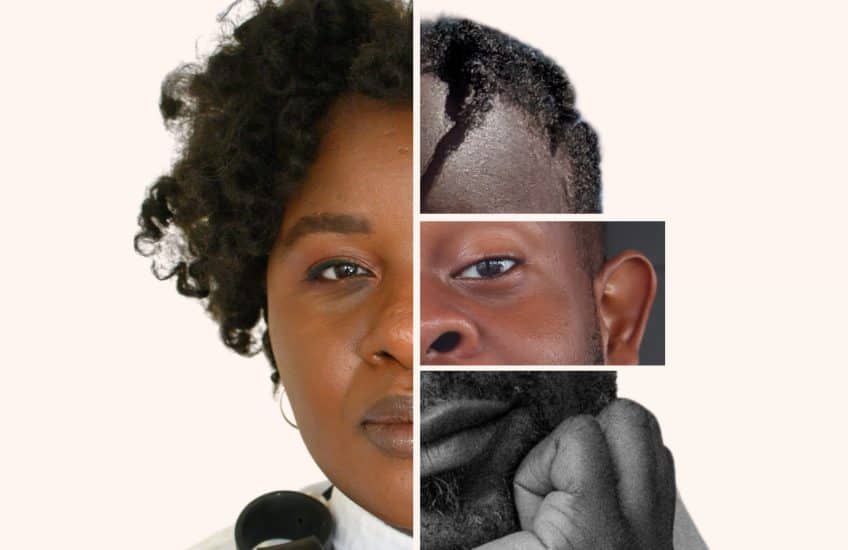

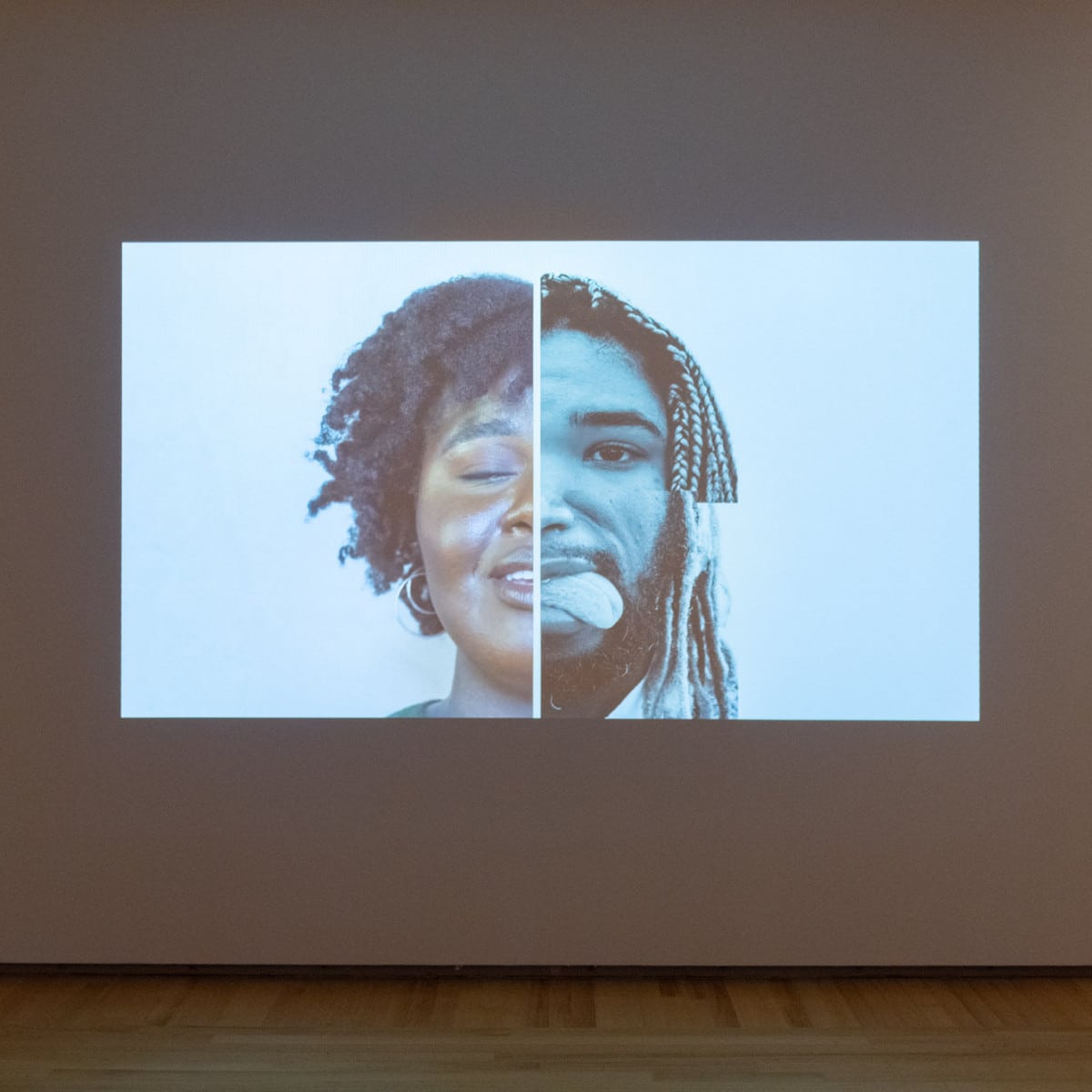

Ezi Odozor: Sure. So, first of all, [I’ll share] a kind of history of where everything came from. Qanita Lilla and Jason Cyrus actually approached me to create a piece that ties together their two exhibitions. Qanita Lilla is curating With Opened Mouths, [and] she’s trying to bring [African] masks out of the space of just being objects for observation. And so it’s the objects in conversation as they are meant to be. And then History Is Rarely Black or White, which is Jason Cyrus’s exhibition, is looking at archival fashion and the relationship between dress and enslavement and the histories of movement of both textiles and the things that were used to dye them and the people that were used to make those textiles, through the picking of cotton and things like that. And so Spirit Banter creates a narrative arc – as they say on the website [laughs] – but it’s a conversation between those two worlds. And so that’s the entry point that I use to start the piece. Who are the people that are trying to be represented in these exhibitions? What are the traditions that are trying to be represented in these two exhibitions? And what are the relationships, not just between people, but these ideas? And so it actually opens the first verse – that’s what the first spirit talks about, you know, deciding who you get to be. This speaks to Jason’s exhibit, which is about dress and how people are able to show up in spaces, depending on their class and depending on their relationship to being either enslaved, formerly a slave, enslaved, et cetera. And then the others are places in which you move through time. Here, where I’ve never been but have always known. And that is a kind of relationship to the spiritual, which is embodied in Qanita’s exhibition. So, the piece, like I said, is a narrative arc, but it’s also a conversation about relationships between people and relationships between ideas. And so that’s how Spirit Banter came to, came to be.

Bruce Kauffman: Oh, thank you very much for that. And I have seen just a little tiny bit of the video behind the glass. I haven’t heard anything yet. And it helped me to understand what I was watching there with what you just explained now. And so you may have already answered it, but what was the inspiration or relation as to why it was created?

Ezi Odozor: Yeah. So, as I said, it came about as, you know, being a conversation between two exhibitions. And then in a lot of my work, I think about relationships: what are our intimate connections? And intimate not just in the sense of pleasure, or those kinds of relationships, but also just the things that kind of go unspoken, or the things that we’re afraid to touch, or like fully speak about. And so intimate in that sense, the things that are near and dear, or the things that are complicated in relation to our feelings. And so, some of the themes I will talk about are things like how we’re claiming agency or questioning the disappearing of, you know, Black bodies — I’ll insist that you see me as part of the poem. And so those are the kinds of spaces that I drew inspiration from, both in the sense of obviously connecting the two exhibitions, but also in the sense of what are the things that I talk about, and how do they show up in this space?

[…]

Bruce Kauffman: What do you feel makes it most interesting, important, or relevant, timely?

Ezi Odozor: I mean, for me, I never necessarily considered talking about Black life as to be untimely.

Bruce Kauffman: Yeah.

Ezi Odozor: Right? It’s always something that is an issue of now, I would say. For me, because I am Black. Right? And so that is my life. But also in just the last two years that we’ve had, and really talking about how Black life shows up, who gets to decide, you know, how long that Black life gets to exist, who gets to interpret what it means, you know, who we are, all that kind of stuff comes into play. And so that is a timely conversation in the sense of the wider world. But I think they are topics that have always been kind of prescient for Black people. So, it’s never out of time, necessarily.

Bruce Kauffman: Wonderful, thank you for that. And can you select three to five key phrases that convey aspects of how to discuss, explain and act your work in greater detail?

Ezi Odozor: I would say a couple of things that are key in terms of engaging with the work, let’s say it that way. First of all, there are four kinds of spirits represented in the piece. And each of the verses is one. There is a way that I presented it from the one, two, three and four. But it can actually be read in any order. And that’s part of the banter. So, banter is supposed to be a jovial exchange, right? But then you have, instead of these poems, like very complex topics. And so it’s kind of, it’s not as light as banter would be. But it’s also taking into account that these are spirits that are doing the banter. And so what might be heavy in a way for a human might not be the same way as it is for a spirit. Also, Black people have always had to have to deal with these very serious topics, and yet live and to have that kind of free exchange. I think “banter” is the keyword in really understanding what the relationship is between “banter” [defined] in the dictionary, and “banter,” what’s actually happening here in this space. Their idea of time is also very important because spirits don’t offer, don’t occupy the same liminal space that we do. And so there’s that one passage that I come back to a lot about “here where I have never been and always known.” And so how we talk about ancestry in relation to Black diasporic peoples. And ancestry being really important in how the ancestors are present, even if they are gone and how we are ancestors, yet to be established within that realm. So, ancestry is an important theme. Time is an important theme. Banter is an important theme. And then I would say agency. So, even as subjects, we’re still agents. And we can sometimes see that in, even in histories of how Black people navigated the Trans Atlantic Slave Trade, in the sense that some people took their lives. And so demonstrating agency even in those moments. Even agency to a little end [sic]. But also not just in death. There’s an agency in our joy too. And we’ve manifested that, right? So, there’s also a line from it that says “not always sorrow, joy too.” So, even in the midst of all of this, there’s agency. So, agency, time, banter — those are all key ideas in this.

[…]

Installation view of Ezi Odozor’s Spirit Banter. Photo: Paul Litherland

Installation view of Ezi Odozor’s Spirit Banter. Photo: Paul Litherland

[…]

Bruce Kauffman: I like to find out about a person’s creative process. I researched you a little bit. I found your LinkedIn page. And I also found a little blurb about you. One thing you mentioned is that you’ve written and/or published in both fiction and non-fiction. Your work focuses on things of identity, culture, gender, race, health and intimacy, which you had already mentioned. And more lately and specifically, you mentioned themes of love, citational politics and anti-colonial interventions for global health. That, and poetry. I’m just curious, between the genres of fiction, non-fiction, poetry, do the words arrive for you differently, like from a different place?

Ezi Odozor: I don’t think so. I don’t think they arrive from a different place because all of it is from my experience. I think that everything anybody does goes through your lens, whatever it is, and however, it comes out finally. I’ve always been a very multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary person. And so just as you’re saying, my work is in health, my work is also in higher-ed, but I also do creative writing. And that has just always been true of me as a person. These are the things that I’m interested in, so this is what I do. And even when I’m writing about global health, the way I’m writing it is that I tend not to write in a super academic way in that sense. It still has rigour, it still has all the things that are needed. But I write in conversational ways, even in the space of writing academic work that is non-fiction. And then in terms of if I’m writing a story, or recently I’ve been doing a lot of screenwriting, even in that, even though there are certain formats. For example, in screenwriting, you write what they’re doing and not all of the things that you would write for say a novel, or to describe every little piece of the relationship and what’s happening outside, you don’t necessarily write that. But even in the style or approach of how I communicate what they’re doing, it’s still very much in view with a kind of poetic narrative for me. Everything to me is storytelling. Everything to me is storytelling. Whether it be I’m telling a story about what needs to happen in the field of global health for it to actually encapsulate good health for all. Or if I’m writing about the fairies on the windowsill. Or if I’m writing about my grandmother’s hands. Or if I’m writing about spirits, it doesn’t matter. To me, it’s all telling a story of what, what’s happening at that moment or in some other moment in time. For me, it’s coming from the same place. I still use a similar style. I just apply that style to the circumstance.