A buckskin dress, a bear-claw necklace, and an ivory Victorian gown. Once worn by the celebrated poet of Mohawk and British heritage, E. Pauline Johnson, these three objects are the focal point of a new exhibition at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre. But are they actually self-portraits?

It’s a question that viewers are prompted to consider in The Artist Herself: Self-Portraits by Canadian Historical Women Artists. Expanding the idea of what self-portraiture can be, the exhibition moves beyond the genre’s traditional association with the human face to propose other forms of self-representation, from both settler and Indigenous perspectives.

A partnership between the Agnes Etherington Art Centre and the Art Gallery of Hamilton, The Artist Herself brings together some 55 works by over 40 artists in a variety of media — including paintings, photograph, film, and textiles such as Johnson’s garments. As co-curator Alicia Boutilier told NGC Magazine in an interview, the poet can be thought of as an early performance artist, one who evoked her dual cultural identity by wearing her “Indian Princess” buckskin dress for the first half of her shows, and a Victorian evening gown for the second half.

Bertha May Ingle, Self-Portrait (c. 1901), oil on canvas. 17 x 17 cm. Private Collection. © Estate of Bertha May Ingle. Photo: Mike Lalich

“It was a way for her to bring her Indigenous culture to a primarily settler audience that would otherwise have not been exposed to it,” said Boutilier. “Johnson drew people in and brought their attention to what was happening to her people,” she adds, referring to Canadian colonial policy and the climate of oppression towards Aboriginal peoples.

Although The Artist Herself features works dating from the late 18th century to the early 1960s, its exploration of self-representation and identity seems particularly relevant in today’s digital era. “Now that people represent themselves on social media in various ways — through parody, photos of objects, or images of different parts of their body — we thought that audiences were ready to think of self-portraiture more broadly,” says Boutilier.

“It’s a timely moment to look back at the kinds of objects that we’ve brought together,” adds co-curator Tobi Bruce. “Contemporary viewers will have a different frame of reference for considering these objects because of the explosion of digital culture.”

Hannah Maynard, Untitled (Tea Time) [c. 1893], modern print from original glass negative. 25.3 x 20.1 cm. Royal BC Museum, BC Archives, Victoria (F-02852). Photo: Courtesy of the Royal BC Museum, BC Archives

Take, for example, Hannah Maynard’s humorous and complex photograph Untitled (Tea Time), one of a series of “selves-portraits” where the photographer-entrepreneur has collaged herself into various scenes. But although it was produced around 1893 — and reflects the type of domestic setting and propriety that would be expected of a Victorian woman — the work has a decidedly contemporary feel. “There is a sense of authority. Maynard is playing with her audience, and she is very self-assured,” says Bruce, who suggests that the photographer’s techniques evoke the current penchant for manipulating digital imagery and constructing multiple selves.

The Artist Herself succeeds in highlighting works by lesser-known artists, such as Maynard and Bertha May Ingle, in tandem with those by some of the most renowned names in Canadian art, including Kenojuak Ashevak, Emily Carr, Daphne Odjig and Paraskeva Clark. The latter is represented by her iconic 1933 self-portrait from the collection of the National Gallery of Canada, Myself. Depicting a poised and confident Clark when she was pregnant with her second son, the painting is exhibited alongside an amauti, an Inuit woman’s parka created around 1918 by Martha Eetak. Featuring a pouch to accommodate a newborn — along with beaded panels, and 701 hand-drilled caribou teeth attached to the fringes — the amauti’s designs are specific to the maker’s life story, experience and community, making it a unique and powerful expression of Eetak’s identity.

Paraskeva Clark, Myself (1933), oil on canvas, 101.6 x 76.7 cm. NGC. © Clive Clark, Estate of Paraskeva Clark. Photo: NGC

“We are trying to create conversations and resonances between different kinds of objects. In some instances it is very clear why an object is a self-portrait; in others, less so,” says Bruce. “But you can move through the exhibition and experience each object as a different reflection on the self, or on personal, communal or familial identity.”

Although Boutilier and Bruce conceptualized the framework for the exhibition, they say that it was realized thanks to many collaborators who shared insights and knowledge with them. Thirty-five different curators, specialists, and writers — including some of the artists’ descendants — have contributed to the exhibition catalogue, a richly illustrated, bilingual publication that features essays on each artist.

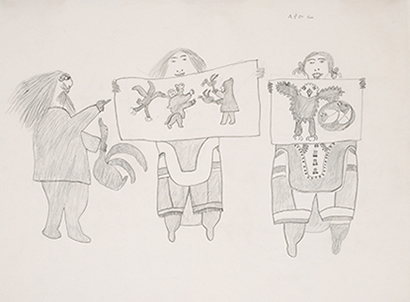

Pitseolak Ashoona, The Critic (c. 1963), graphite on wove paper, 47.6 x 61.1 cm. NGC. Gift of the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, 1989 (36404). © Dorset Fine Arts. Photo: NGC

The Artist Herself culminates with Pitseolak Ashoona’s The Critic, a drawing on loan from the National Gallery. Dating from around 1963, it depicts a critic and two artists, one of which is thought to be Ashoona holding up a drawing of herself. In addition to slyly asserting Ashoona’s identity as an artist, the work also heralds the rise of Inuit graphics and an interest in self-portraiture among subsequent generations of Inuit artists — making it not so much an ending, notes Boutilier, but a beginning.

The Artist Herself: Self-Portraits by Canadian Historical Women Artists is on view at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario until August 9, 2015. It then travels to the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria and the Kelowna Art Gallery, before closing at the Art Gallery of Hamilton in the summer of 2016. However, visitors keen to see Pauline Johnson’s buckskin dress will want to pay a visit to the Agnes: due to the object’s fragile condition, it is unable to tour.

By Robyn Jeffrey

-link to article