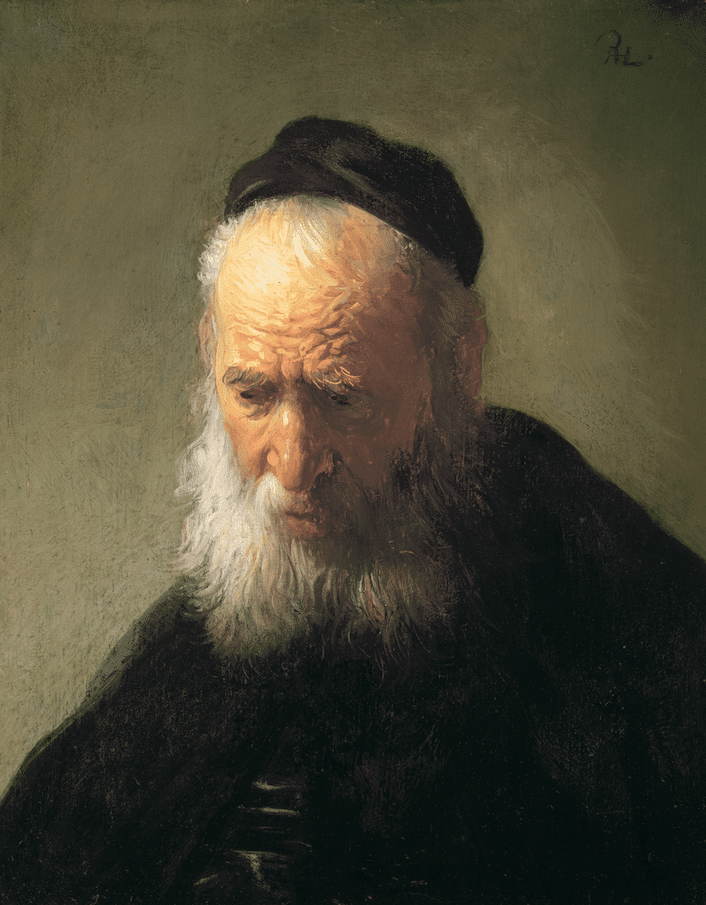

In the preface to Pictures from the Age of Rembrandt: Selections from the Personal Collection of Dr & Mrs Alfred Bader, Alfred Bader wrote of his “pleasure-in-anticipation” of the show of his personal collection, for Dutch paintings, and those of the School of Rembrandt in particular, were his first love.”1“My main interest has been paintings of the School of Rembrandt, preferably of Biblical subjects.” As noted in Alfred Bader’s preface, this is the first exhibition of paintings from his personal collection, which was housed in Milwaukee (USA), in Canada. Alfred Bader, “Preface,” in David McTavish, Pictures from the Age of Rembrandt: Selections from the Personal Collection of Dr & Mrs Alfred Bader (Kingston, ON: Agnes Etherington Art Centre, 1984), viii and ix. The first formal exhibition of Bader paintings at Agnes—paintings that had already been incorporated into the permanent collection—was in 1982 (see note 14). As only the second exhibition of Bader paintings, Pictures from the Age of Rembrandt featured work by such artists as Jan Lievens, Jacobus Vrel, Michiel Sweerts, and Cornelis Bega, and they represented the full scope of Dutch painting of the seventeenth century: portraiture, biblical subjects, still life and genre scenes. More than half of the thirty-six works exhibited in 1984 have since entered into The Bader Collection at Agnes, including its first Rembrandt, Head of an Old Man in a Cap.

Until late 2022 and as anticipated in Agnes Reimagined, The Bader Collection of European painting at Agnes was presented through temporary exhibitions. This meant that only a small percentage of objects in the collection were on display at any given time, rotating every four months to two years, depending on the exhibition’s run. Each exhibition advanced a new narrative premise for a different group of objects, which allowed for continuous rethinking of the collection.2Current ambitions for the new Agnes building maintain the temporary exhibitions programming model. With increased gallery space, however, a higher percentage of The Bader Collection will be on view, and some exhibitions will have longer durations. The success of this format demonstrates the dynamism and multivalency of paintings, and it offers a captivating lens through which to consider The Bader Collection.

This essay will explore how the collection has been presented through exhibitions to create cultural meaning, thereby advancing the import of individual objects through a never-ending array of narrative structures. By examining how The Bader Collection has been illuminated for the public through temporary exhibitions, this text seeks to establish how this incredible collection of paintings has framed and negotiated the significance of historical European art for Agnes’s audiences. It will also consider the critical narratives that have been surfaced through the collection, explore the innovative ways that the collection has been positioned to speak to the most pressing issues of the human experience, and highlight the essential role of the collection’s curators in the performance of exhibition work.

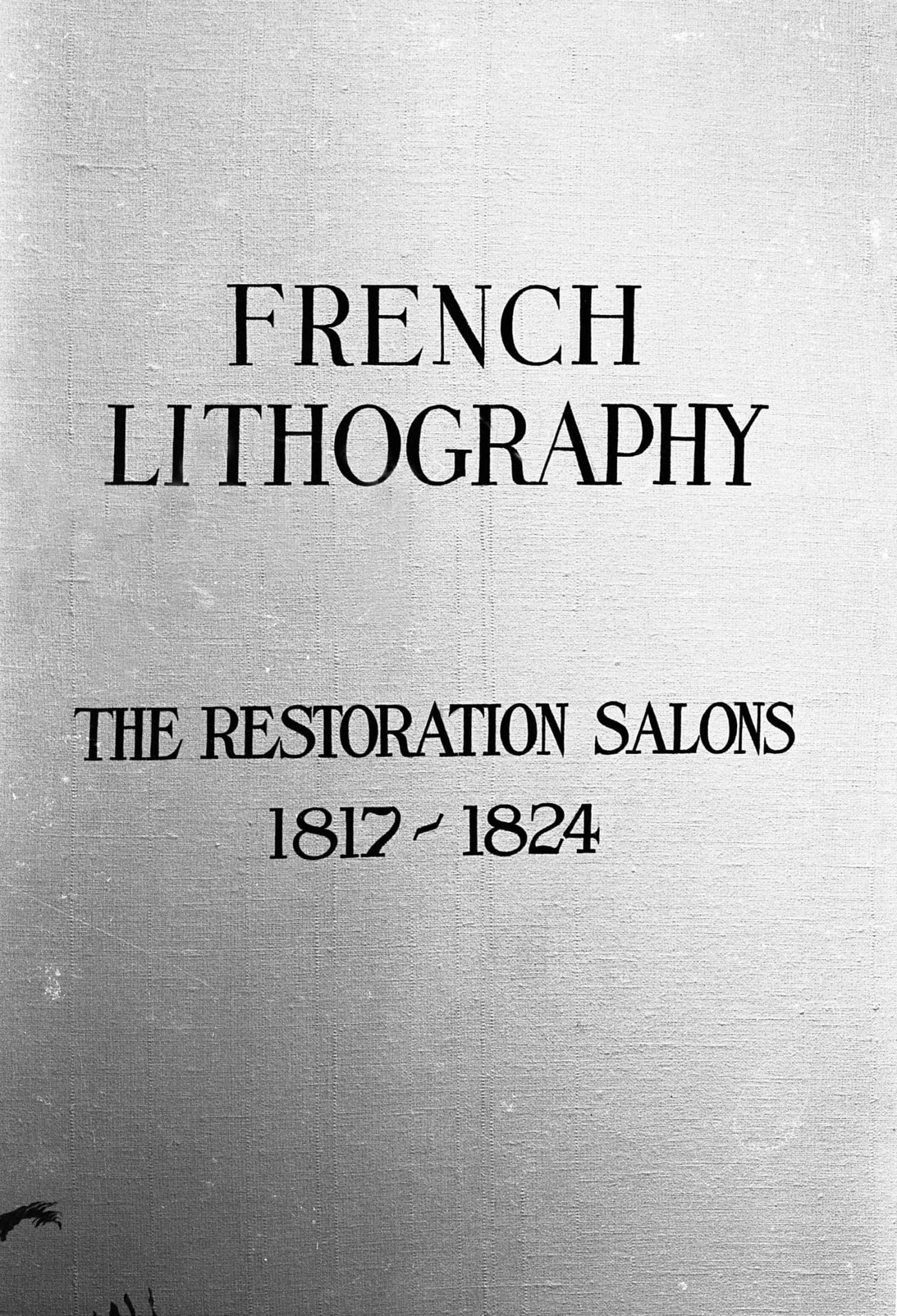

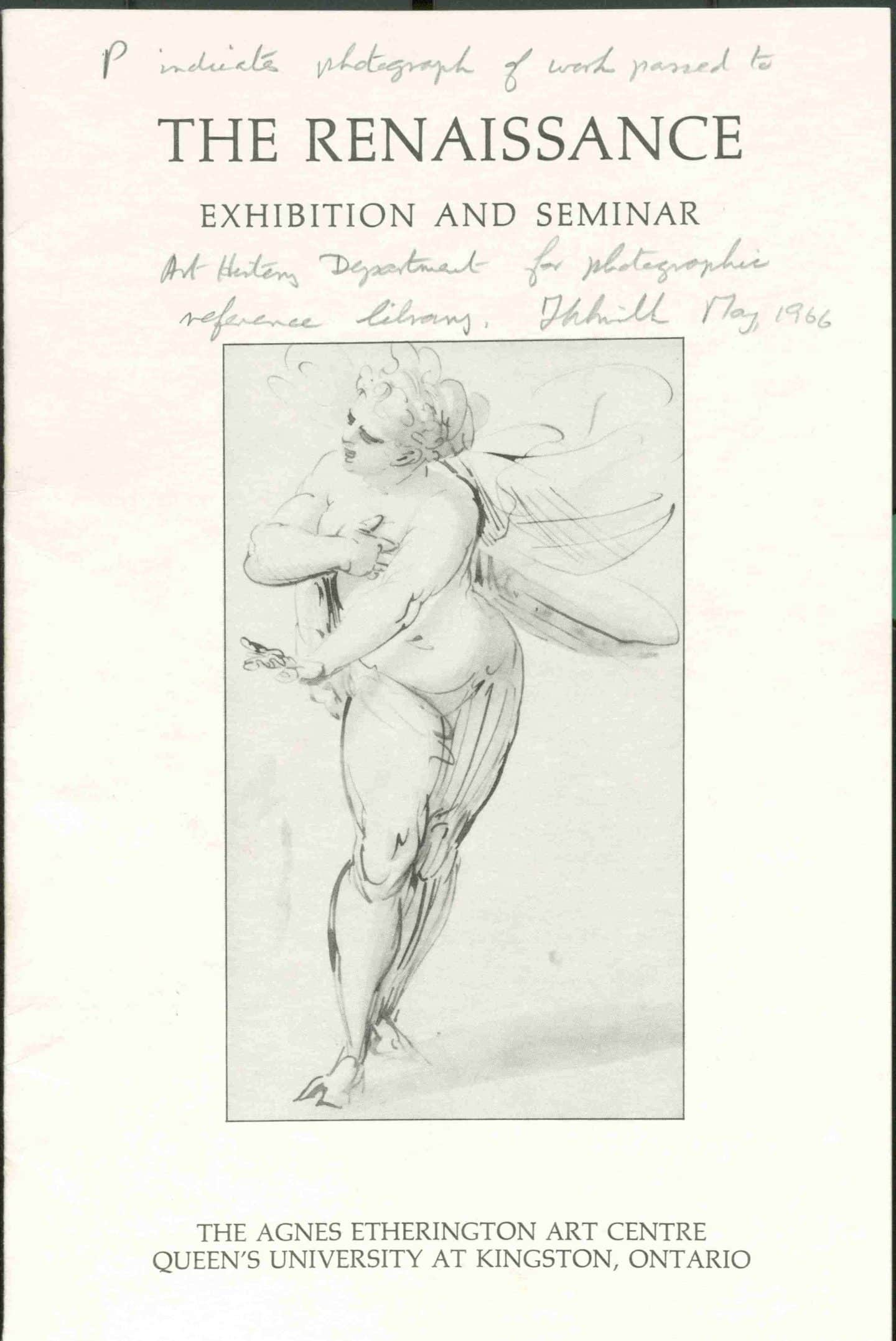

Exhibitions of European art at Agnes prior to the major gift of Bader paintings were extremely varied in scope, as they depended on the offerings of other institutions and the interests of Queen’s faculty. The first exhibition of historical European art at Agnes was, in fact, within the first year of the gallery’s opening, in April 1958.3It was an exhibition of reproductions of Venetian paintings: Venetian Painting, 1 April—19 April 1958. Unless otherwise indicated, all exhibition data is drawn from Tabitha Minns and Heather Savage, “Roll Out: Agnes Etherington Art Centre Exhibition History 1957 through 1991” and authors unknown, “Agnes Etherington Art Centre Exhibition History 1992 through 2013,” both typewritten, unpaginated manuscripts located at Agnes. For approximately the next twenty-five years, historical European exhibitions comprised primarily works on paper and were circulated by larger institutions with more extensive collections, including the National Gallery of Canada,4Recent Acquisitions of Prints and Drawings, 8-31 March 1963, with European and Canadian artists from four centuries; Two British Satirists: Hogarth and Rowlandson, 28 February-22 March 1964 (organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and circulated by the National Gallery of Canada); Recent Accessions of Prints and Drawings, 18 February-13 March 1966, with European and Canadian works (organized by the National Gallery of Canada); Early English Watercolours, 6-27 November 1966 (organized by the National Gallery of Canada and circulated by the Art Institute of Ontario); Nineteenth Century France, 29 January-23 February 1969 (organized by the National Gallery of Canada); Dutch Graphic Art, 5-28 September 1971 (organized by the Dutch Ministry of Cultural Affairs and circulated by the National Gallery of Canada); Venetian Prints of the XVIIIth Century, 16 January-15 February 1972 (circulated by the National Gallery of Canada); Recent Acquisitions of Old Master Drawings, 15 February-15 March 1975 (organized by the National Gallery of Canada); and Tiepolo Etchings, 6 January-1 February 1976 (organized by the National Gallery of Canada). the Art Gallery of Ontario,5English Watercolours and Drawings, 2 February-3 March 1968 (organized by the Art Gallery of Ontario); Four Centuries of Master Drawings, 6-26 October 1969, with selected works from the Art Gallery of Ontario; French Nineteenth Century Printmakers, 14 November-31 December 1974, with selected works from the Art Gallery of Ontario; and Italian Old Master Drawings, 18 January-1 March 1981 (organized by the Art Gallery of Ontario). the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts,6Nineteenth Century Small Paintings and Oil Sketches, 7 November-8 December 1980 (organized by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts). American institutions,7The Baroque Illusion, 29 November-22 December 1959, curated by Dr Richard Wunder (circulated by Cooper Union Museum). and smaller, sometimes commercial, entities.8Wedgwood Varieties – Museum Exhibition, 25 April-29 May 1966 (organized by the Buten Museum of Wedgwood (Merion, Pennsylvania)); and Rodin and His Contemporaries, 4-12 August 1971 (organized by Rothman’s of Pall Mall Canada Limited); and Eighteenth Century Stage: Britain, 10 November-2 December 1973 (organized by the Department of Prints and Drawings at the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Saskatoon Gallery and Conservancy Corporation). When Agnes did organize an exhibition of historical European art during these early years, it typically focused on prints or drawings from the collection, sometimes supplemented by loans from North American collections,9Romanticism: Drawings and Watercolours, 10-27 January 1965, with objects from the National Gallery of Canada, the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Fogg Museum of Harvard University, and the Smith College Museum (organized by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre); Dutch Genre and Landscapes, 30 July-14 September 1977, organized from the collection of the Agnes Etherington Art Centre; Nicolas Toussaint Charlet 1792-1845: Un Alphabet Moral et Philosophique, 17 March-30 April 1978 (organized by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre); French Nineteenth Century Etchings, 22 September-4 November 1979, organized from the collection of the Agnes Etherington Art Centre; Edward Lear: Lithographs of Rome, 16 July-7 September 1980, organized from the collection of the Agnes Etherington Art Centre; Jan Punt Engravings of Rubens’ Antwerp Ceiling, 6 February-25 March 1981, organized from the collection of the Agnes Etherington Art Centre; European Drawings from the Collection, 15 May-28 June 1981 (organized by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre); and Tissot Prints, ?-8 November 1981 (organized by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre). A notable exception was the first show of Northern European painting held at Agnes, Little Masters of Dutch and Flemish Painting, 6-29 October 1961, featuring works by Ludolf Backhuizen, Peter Paul Rubens and David Teniers from the National Loan Collection Trust (London, UK) (circulated by the National Gallery of Canada). and was curated by faculty members of the Department of Art and other institutions.10Drawings and Prints of the Renaissance, 9-30 January 1966, curated by Professor J. Douglas Stewart, Department of Art, Queen’s University; Romantic Art: the Lure of the Antique and the Exotic, 29 October-12 November 1969, curated by Professor George Keyes, Department of Art, Queen’s University; German Renaissance Graphics, 4-28 March 1971, curated by Professor George Keyes, Department of Art, Queen’s University; Architects and the Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1769-1785, 6-25 February 1976, organized by Professor Pierre du Prey, with students of Art History 397; French Lithography: The Restoration Salons 1817-1824, 15 October-30 November 1976, organized and curated by Professor W. McAllister Johnson, University of Toronto; and Baroque Architectural Drawings from the Phyllis Lambert Collection, 28 January-22 February 1979, curated by Professor Pierre du Prey, with students of Art History 397.

Overall, there was a clear preference for Italian Renaissance and, foremost, British art within the community.11The Massey Collection of English Paintings, 16 December 1966-6 January 1967 (organized by the National Gallery of Canada); Silver Exhibition, January-February 1968, with selections from the collection Dr. Stuart W. Houston and Dr. J.F. Houston (organized by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre); British Domestic Silver, 23-30 March 1969 (organized by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre); British Silver, January 1975, with selections from the Houston gift (organized by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre); William Hogarth: A Rake’s Progress and Other Engravings from the Collection of Mr. Tony Miller, 4 October-2 November 1975 (organized by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre); British Domestic Silver, 23 Februay-30 April 1977 (organized by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre); In the Print Room, 19 March-17 April 1977, with prints by William Blake (organized by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre); British Domestic Silver, 1 March-30 April 1979 (organized by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre); English Landscape Mezzotints, 2 February-9 March 1980 (organized by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre); and Illustrated Books of the 19th Century, 6 June-19 July 1981 (organized by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre). As Agnes began to acquire a larger collection of European paintings, starting with the first gift by Alfred Bader in 1967,12The 1966 exhibition Drawings and Prints of the Renaissance (see note 10) was the show that prompted the loan and eventual gift, one year later, of the Salvator Mundi by Alfred Bader. the occasional paintings exhibition became possible.13Master Paintings, 28 October-9 November 1971, with a loan of an El Greco painting from the National Gallery of Canada and selected works from the Bader gift (organized by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre); and European Works, 9 February-12 March 1975, with works from the Bader gift (organized by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre).

Agnes established its identity as a university hub for the study of European historical painting in Canada.

In 1982, the first exhibition to exclusively feature paintings from what was then known as “the Bader gift” was mounted,14Permanent Collection: The Bader Gift, 1 May-30 June 1982 (organized by the Agnes Etherington Art Centre). igniting an increasing focus on Baroque painting at Queen’s, though exhibitions of prints and silver curated from the permanent collection would continue.15British Prints from the Permanent Collection, 25 August-11 October 1982; French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture Engraved Reception Pieces, 29 August-3 October 1982; British Prints from the Permanent Collection, 16 August-9 October 1983; Dutch Prints from the Permanent Collection, 12 October-1 November 1983; The Age of Elegance: British Tablewares 1775-1825, 5 November-6 December 1983, with selections from Kingston-area collections; Selections from the Silver Collection, 10 January-26 February 1984; and German Prints from the Permanent Collection, 20 March-22 April 1984. In addition, exhibitions continued to be borrowed from major Canadian collections: Italian Prints 1500-1800, 6 January-5 February 1984 (organized by the Art Gallery of Ontario); The Hague School: Collecting in Canada at the Turn of the Century, 27 April-27 May 1984 (organized by the Art Gallery of Ontario); and 18th Century Venetian Art in Canadian Collections, 17 June-5 August 1990, curated by Dr. George Knox (organized by the Vancouver Art Gallery).The approximately forty paintings presented to Agnes by 1982 cut a broad swath across Europe, from Italy to England to the United Provinces of the Netherlands to France, and the gift was exhibited in selections throughout the mid-1980s.16Selections from the Bader Gift, 1 July-4 August 1985; and Selections from the Bader Gift, 11 November 1986-1 February 1987.

By the late 1980s, the number of Bader paintings presented to Agnes had grown to approximately one hundred. Thirty-six paintings from the Bader gift were united in the exhibition Telling Images: Selections from the Bader Gift of European Paintings to Queen’s University, which traveled to seven smaller venues across Canada between 1989 and 1991. This exhibition not only introduced the deep generosity of the Baders to new audiences, but it brought high-quality historical European painting to centres that did not possess strong collections of Baroque art.17As Alfred and Isabel Bader wrote in the preface: “We are particularly happy that it [the exhibition] will travel in Canada from coast to coast because most Canadian museums have been founded in this century and specialize in Canadian and modern art. Apart from the collections of the National Gallery and the Museums of Montreal and Toronto, there are very few old master paintings on view in Canada. Unless widely travelled, most Canadians have had little opportunity to study and enjoy old masters.” See Alfred and Isabel Bader, “Donors’ Preface,” in David McTavish, Telling Images: Selections from the Bader Gift of European Paintings to Queen’s University (Kingston, ON: Agnes Etherington Art Centre, 1988), x. With this exhibition, and the gift of another seventeen paintings to the collection in 1991,18This gift of seventeen paintings accelerated the number of Bader exhibitions: Recent Gifts from Dr. Alfred and Isabel Bader, 11 November 1990-17 March 1991; Baroque Paintings of 17th Century Europe, 21 July-13 October 1991; The Bader Collection: European Paintings, 5 November-6 December 1991; The Bader Gift: A Selection from the Permanent Collection, 23 August 1992-21 March 1993, curated by Dorothy Farr; British Painting from the Permanent Collection, 28 March-19 December 1993, curated by Dorothy Farr; and Highlights from the Bader Collection, 13 August-11 February 1996, curated by Dorothy Farr. Agnes established its identity as a university hub for the study of European historical painting in Canada.19This was supported by the creation of a graduate program in Art History and the Bader Chair in Northern European Art, both in 1994. The Bader Chair in Southern European Art was established in 2002. See David de Witt, “For the Love of Paintings,” in The Bader Collection: Dutch and Flemish Paintings (Kingston, ON: Agnes Etherington Art Centre, 2008), 13.

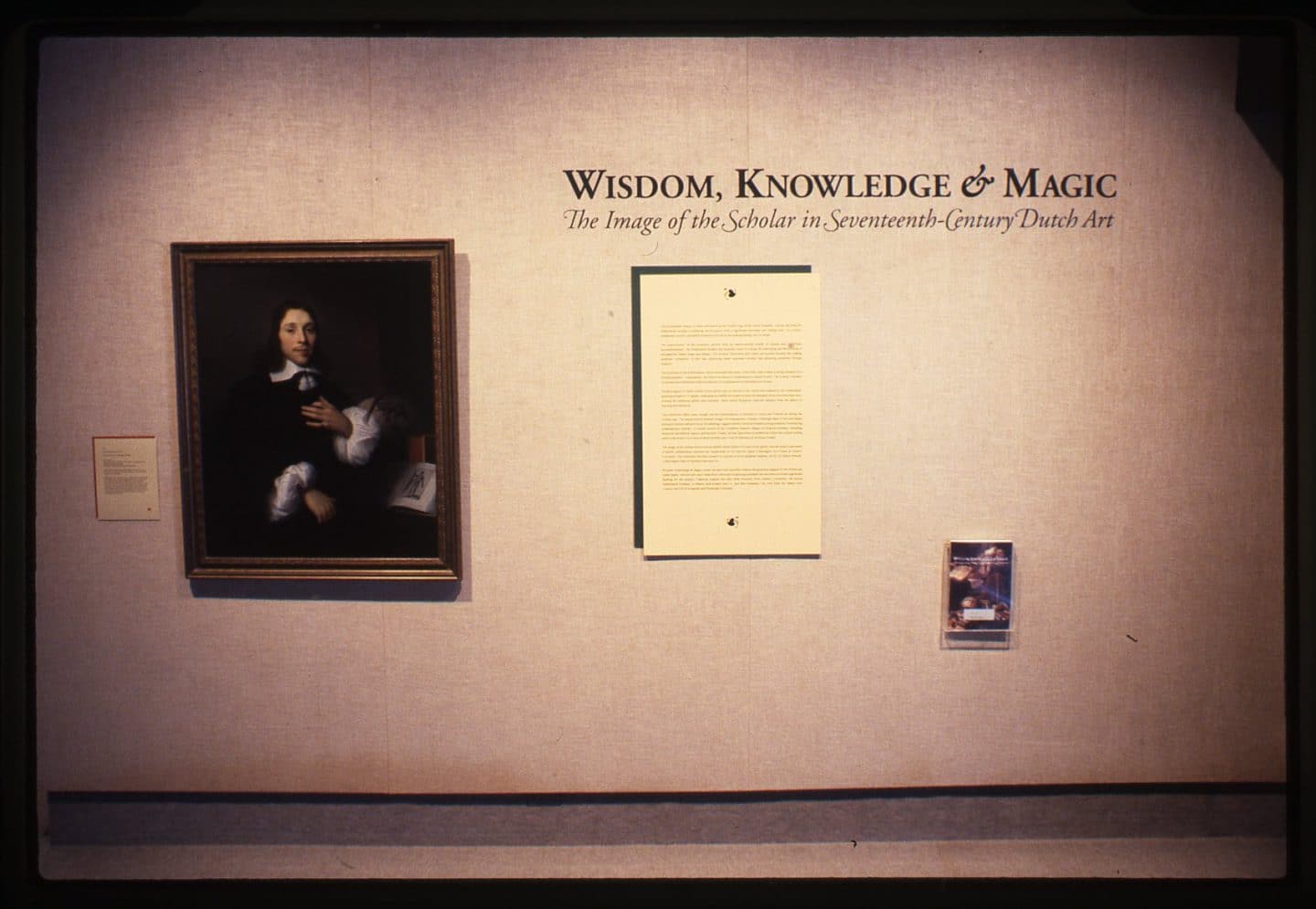

This was further evinced through the exhibition Wisdom, Knowledge & Magic: The Image of the Scholar in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art in 1996, which was accompanied by a catalogue with essays and entries written with significant participation from students in the recently founded graduate program in art history. The list of exhibited works included eight objects from Agnes’s permanent collection, twelve from other collections—the Art Gallery of Ontario, the National Gallery of Canada, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art—and eighteen from the Baders’ personal collection in Milwaukee. This exhibition revealed the degree to which Agnes’s collection of Northern Baroque art had truly become integrated into the fabric of important North American collections.

In 2001, when the historical European collection received an endowed curatorship intended to bring “specialized expertise to the care and presentation of the collection,”20David de Witt, “For the Love of Paintings,” in The Bader Collection: Dutch and Flemish Paintings (Kingston, ON: Agnes Etherington Art Centre, 2008), 14. the exhibition activity related to The Bader Collection was amplified dramatically.21This was further enhanced by the designation of a dedicated exhibition space for the collection, “The Bader Gallery,” with the expansion of Agnes in 2000. As each scholar who has held the position of Bader Curator of European Art has specialized in the art of the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic, exhibitions have increasingly concentrated on Northern Europe, particularly as gifts of art to Agnes have continued.

With the presentation in 2003 of the first of three Rembrandt paintings,22A second painting, Head of an Old Man in a Turban (Study for a Rabbi?), entered the collection in 2007, and Portrait of a Man with Arms Akimbo entered in 2015, both as gifts from Drs Alfred and Isabel Bader. the aforementioned Head of an Old Man in a Cap, Drs Alfred and Isabel Bader further underlined the distinct Dutch character of the collection. The related exhibition Gift of Genius: A Rembrandt for Kingston, discussed further below, announced Agnes’s profile as one of only four Canadian institutions with a painting by the Dutch master. While subsequent Agnes exhibitions often adopted a pan-European look at Baroque painting23The Contemplative Imagination, 3 February 2002-17 August 2003, curated by David de Witt; The Imitation of the Artist, 16 October-18 December 2005, curated by David de Witt; Wrought Emotions: European Paintings from the Permanent Collection, 28 August 2005-26 January 2007, curated by David de Witt; An Enduring Passion: The Bader Collection, 2 September 2007-6 January 2008, curated by David de Witt; Dramatic Turns: Narratives of Change in European Painting, 20 January-14 December 2008, curated by David de Witt; Poet, Priest, Dauber: The Painter in Renaissance and Baroque Eras, 17 January 2009-9 May 2010, curated by David de Witt; Discord and Harmony: Themes of the Baroque Era, 12 June 2010-29 May 2011, curated by David de Witt; Diamonds in the Rough: Discoveries in The Bader Collection, 18 June 2011-12 August 2012, curated by David de Witt; Masters of Time, 11 May 2013-24 November 2013, curated by David de Witt; Rome: Capital of Painting, 5 January-5 August 2019, curated by Jacquelyn N. Coutré; Artists at Work: Picturing Practice in the European Tradition, 28 April-2 December 2018, curated by Jacquelyn N. Coutré; The Powers of Women: Female Fortitude in European Art, 6 January-8 April 2018, curated by Jacquelyn N. Coutré; and Alfred Bader Collects: Celebrating Fifty Years of The Bader Collection, 29 April-3 December 2017, curated by Jacquelyn N. Coutré.—an entirely reasonable approach, given the mobility of artists, artworks and patrons during this period—the specifically Dutch component was elevated in such exhibitions as Artists in Amsterdam (2015); Singular Figures: Portraits and Character Studies in Northern Baroque Painting (2016), Rembrandt: Beneath the Surface of Portrait of a Man with Arms Akimbo (2017), Leiden circa 1630: Rembrandt Emerges (2019-2020), and Rembrandt and Company: Seventeenth-Century Dutch Paintings from The Bader Collection (2020-2021).24Artists in Amsterdam, 10 January-6 December 2015, curated by David de Witt; Singular Figures: Portraits and Character Studies in Northern Baroque Painting, 9 January-4 December 2016, curated by Professor Stephanie S. Dickey, Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art and Jacquelyn N. Coutré; Rembrandt: Beneath the Surface of Portrait of a Man with Arms Akimbo, 7 January-9 April 2017, curated by Jacquelyn N. Coutré; Leiden circa 1630: Rembrandt Emerges, 24 August-1 December 2019, curated by Jacquelyn N. Coutré; and Rembrandt and Company: Seventeenth-Century Dutch Paintings from The Bader Collection, 5 September 2020-15 August 2021, curated by Professor Stephanie S. Dickey, Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art.

With a total of four paintings by Rembrandt in the collection by mid-2019,25A fourth, Head of an Old Man with Curly Hair, was presented to Agnes by Bader’s son Daniel and his wife Linda in 2019 in memory of Bader. This painting had been acquired by Alfred Bader in 1993 and was subsequently given to Daniel. Recent gifts to Agnes by Isabel Bader include several paintings in the close orbit of the artist: Attributed to Rembrandt van Rijn, A Scholar by Candlelight, around 1628-29; Unknown artist (after Rembrandt van Rijn), Head of an Old Woman, around 1630; and Attributed to Rembrandt van Rijn, Head of a Bearded Man: Study for St. Matthew, 1657. Among these gifts is also a number of paintings by known students and followers of the artist. Agnes could be considered the most significant centre for the study of Dutch art at Canadian university museums and the strongest collection of Rembrandt and Rembrandt School paintings in Canada, as Alfred Bader intended.26“The Bader Collection,” video, 1982.

With exhibitions as the sole way of sharing The Bader Collection with the public, their role as makers of meaning is crucial to the larger discussion of their histories. As described in a 1996 anthology dedicated to the philosophy of exhibitions, exhibitions are “the primary site of exchange in the political economy of art, where signification is constructed, maintained and occasionally deconstructed.”27See “Introduction,” in Thinking about Exhibitions, ed. Reese Greenberg, Bruce W. Ferguson, and Sandy Nairne (London/New York: Routledge, 1996), 2. Through a carefully crafted narrative, exhibitions can surface untold histories, chart alternative courses for the past, and create new knowledges between discrete artworks. Rather than adhering to strict chronological or monographic exhibitions, exhibitions of The Bader Collection have been configured to visualize ideas related to art history, such as attribution, collecting practices, and contemporary social issues.

Given the breadth of The Bader Collection, a number of exhibitions have investigated specific art historical moments. Artists in Amsterdam, curated in 2015 by then-Bader Curator of European Art David de Witt, sought to establish the visual context of the flourishing art centre of Amsterdam between the 1630s and the 1670s—precisely the period in which Rembrandt was active in the city. It traced the socio-cultural path from the dominant influence of Italian art, interpreted by the early painter Jacob Pynas, through that of the Flemish or International style exemplified by Adam Camerarius, through the final classicizing influence, as seen in the work of Johannes Lingelbach, providing a microcosm of seventeenth-century Dutch art through the vocabulary of Amsterdam painters. It demonstrated the range of artistic styles popular in the metropolis, thereby throwing into relief the decisions made by Rembrandt and those in his orbit on the competitive art market.

Similarly, Rome, Capital of Painting, curated in 2019 by then-Bader Curator and Researcher of European Art Jacquelyn N. Coutré, explored the lively art scene generated by ambitious artists from across Europe who journeyed to the Eternal City throughout the seventeenth century. They basked in the inspiration fueled by the city’s ancient and modern artistic traditions, producing prints and drawings of classical statues and buildings, and paintings inspired by classical tales and Roman collections. The selection of objects reflected the manners pioneered by artists who cast large shadows in the city—Adam Elsheimer, Nicolas Poussin, Michelangelo da Caravaggio, and Annibale Carracci—manners that were then disseminated across Europe when these artists returned to their homelands. Like Artists in Amsterdam, Rome, Capital of Painting used the notion of “place” to prompt conversations about competing artistic styles and the development of the art market.

Many paintings in The Bader Collection have had previously contested attributions, and a few exhibitions have delved into how the act of connoisseurship is performed by curators. One of the most important examples of this approach is the 2003—2004 exhibition Gift of Genius: A Rembrandt for Kingston, organized by De Witt in celebration of the newly donated Head of an Old Man in a Cap.

This exhibition featured the recent acquisition—which had been purchased by Alfred Bader in 1979 as an unknown follower of Rembrandt van Rijn, in spite of the visible “RHL” monogram at the upper right—paired with its reproductive etching by Jan van Vliet and prints by the two artists. Presenting a focused exhibition of only twelve works (the painting plus eleven etchings), De Witt privileged the painting and emphasised the highly recognizable painting style, including the unblended strokes and the scratching into the painted surface, as quintessential of the artist’s early work. The reproductive etching by Van Vliet, with its inscription of “RH inventor,” and the other Rembrandt-inspired prints highlighted the close working relationship between the two Leiden artists and thereby legitimized the monogram on the painting.28The impression of Van Vliet’s etching had entered the collection the year prior, in 2002, as a gift of Daphne and Ned Franks. Gift of Genius made an argument for attribution through both stylistic and documentary evidence, thereby pulling the curtain back on curatorial method. A similar approach was taken in 2011 with Lost and Found: Wright of Derby’s View of Gibraltar, an exhibition co-organized by then-director Janet M. Brooke and De Witt around a 2001 gift formerly attributed to the great eighteenth century English painter, Joseph Wright of Derby. The consummation of ten years of technical, provenance, and stylistic research on the painting by members of the Queen’s community,29The catalogue features essays by the exhibition’s organizers and then Professor of Paintings Conservation, Barbara Klempan. the exhibition presented A View of Gibraltar during the Destruction of the Spanish Floating Batteries on the 13th of September, 1782 with eight landscapes by the artist from the permanent collection to foreground the contested painting’s authorship and high quality, and to posit a renewed attribution to Wright of Derby.30De Witt has since revised his opinion on the attribution. See David de Witt, The Bader Collection: European Paintings (Kingston, ON: Agnes Etherington Art Centre, 2014), 146-49. By addressing attribution as a primary theme, these exhibitions demonstrated and celebrated the research performed by Agnes’s curators and affiliated Queen’s faculty.

Neither Gift of Genius nor Lost and Found prioritized the collecting stories behind the paintings on view, and it was with the 50th anniversary of Alfred Bader’s first gift to Queen’s in 2017 that those accounts were assembled. Alfred Bader Collects: Celebrating Fifty Years of The Bader Collection, curated by Coutré, marshalled the collection to paint a portrait of Alfred Bader as a connoisseur and scholar. It highlighted intellectual and emotional connections to specific works, from the resonance of the subject of Jacob’s Dream for a war refugee in Montreal in the 1940s to the recognition of Solomon’s Idolatry as a poignant demonstration of the many failings of humankind in the Bible. The object labels featured quotations from Alfred Bader about these beloved works. His love of “puzzle paintings,” his belief that art offers solace and a deeper understanding of the human condition, and his passionate support of Queen’s via his gifts of art were brought out through the selected paintings. Such collecting histories offered fascinating insights into the contours of The Bader Collection and into the personality of one of Queen’s most generous donors.

In recent years, The Bader Collection has been mobilized to reflect imperative social issues. The Powers of Women: Female Fortitude in European Art, curated by Coutré in 2018 and organized to coincide with International Women’s Day (and unintentionally aligning with the early moments of the #MeToo movement), drew inspiration from the medieval theme of die Weibermacht (“the power of women”), which characterized women as profiting from their sexual wiles to manipulate and overcome male Christian virtue.31The fundamental exploration of this subject, which inspired the exhibition, is Susan L. Smith, The Power of Women. A Topos in Medieval Art and Literature (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995). Looking beyond the subjects canonical to this theme, such as Joseph and Potiphar’s wife, Susanna and the Elders, and Samson and Delilah, the exhibition broadened the lens on female power to consider images of strong women using their minds and bodies to test the boundaries of gender hierarchies. As no female artists were represented in The Bader Collection, such depictions of women by early modern male painters invited honest conversations about the male gaze, the condemnation of women’s “unruly” behavior by men, and the reclaiming of female agency through subversion.

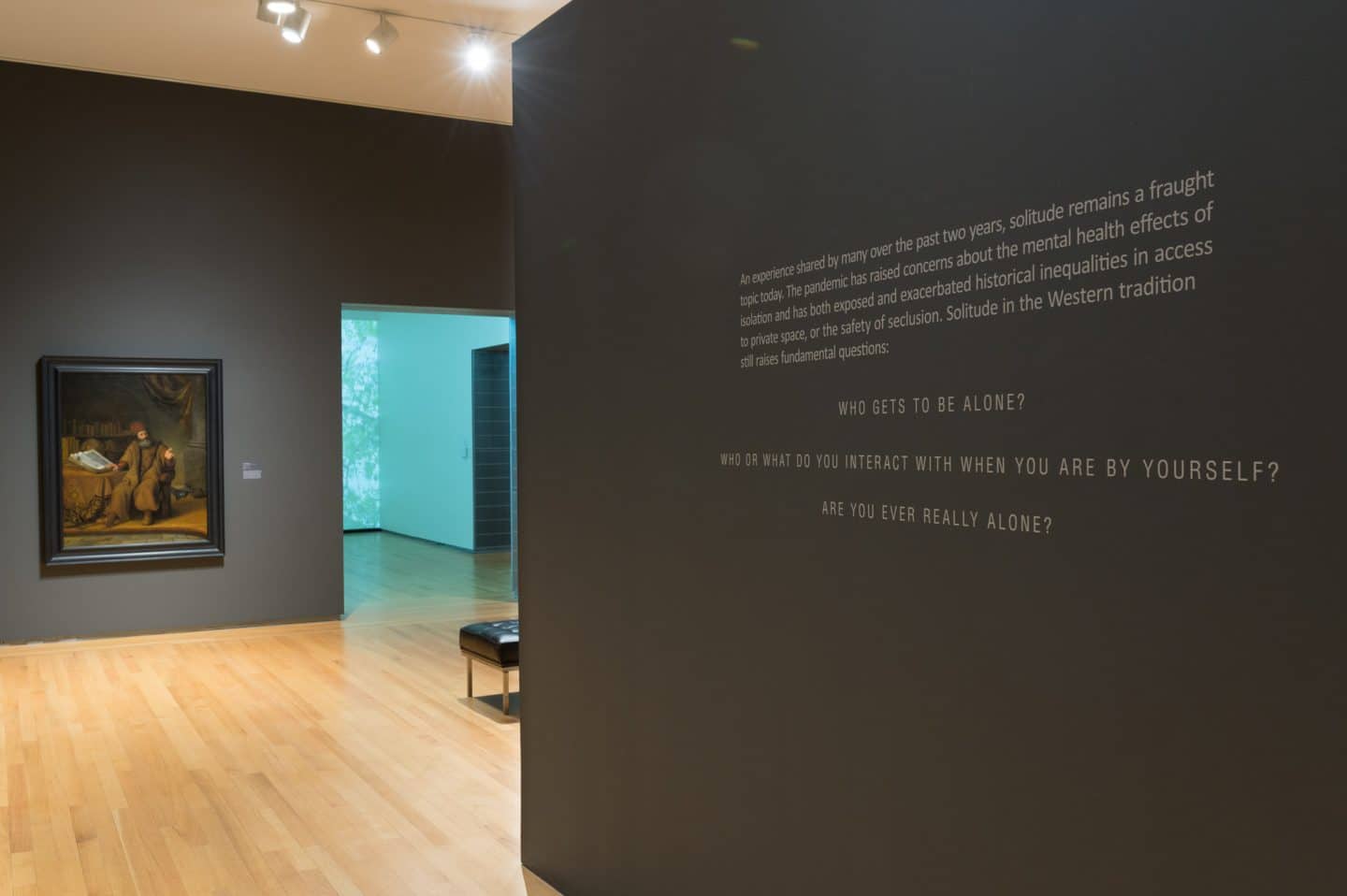

Similarly, the recent Studies in Solitude: The Art of Depicting Seclusion, organized by Bader Curator of European Art Suzanne van de Meerendonk in 2021—2022, probed the question of solitude and seclusion as related to moral rectitude and piety. Images such as A Scholar by Candlelight, attributed to Rembrandt van Rijn, highlight the long-held notion that the (inherently male) sage necessitated isolation in order to achieve his scholarly ambitions, and that those ambitions were fundamentally pure, admirable, and indisputable. Framed by the worldwide Covid-19 pandemic, the exhibition sought to articulate the boundaries of solitude and the work accomplished in it, to inquire about who has been permitted the luxury of solitude, and to test the limits of human interiority in a quest to surface the enduring privileges associated with space, work and gender.

The Bader Collection, through 2022, has shown itself to be very adaptable through its ability to speak to so many compelling exhibition premises. But these premises could not have been manifested without the vision of the collection’s stewards.

In 1996, Hans-Ulrich Obrist described the task of the curator as “that of a catalyst, a pedestrian bridge between the art and the public,”32Hans-Ulrich Obrist, “Curator Interview,” Artforum 35, no. 3 (November 1996): 125. In this article, Obrist ascribes this quotation to the nineteenth-century art critic Félix Fénéon. Fénéon specialist Joan Halperin has found no evidence for this attribution. Personal communication with the author, 22 September 2022. and this analogy is particularly relevant for The Bader Collection, a collection founded by an innovator in the field of chemistry. As a catalyst, the curator is responsible for fostering dialogues between works of art, as well as generating inspiring experiences between viewers and artworks. Each of the three Bader curators has adopted a specific curatorial approach, which has been shaped by their understanding of the function of art, their research interests, and their conceptualization of The Bader Collection. All three Bader curators have also taken their responsibility as “exhibition-makers” seriously to facilitate the expansion of art’s meaning, as Robert Storr has written.33Robert Storr, “Show and Tell,” in Paula Marincola, ed., What Makes a Great Exhibition? (Philadelphia: The Pew Center for Arts and Heritage, 2015), 31. Storr draws upon a term coined by the acclaimed curator Harald Szeemann, Austellungsmacher (exhibition-maker), as a descriptor for a new generation of curators who engage primarily with the organization of exhibitions, rather than the custody of collections.

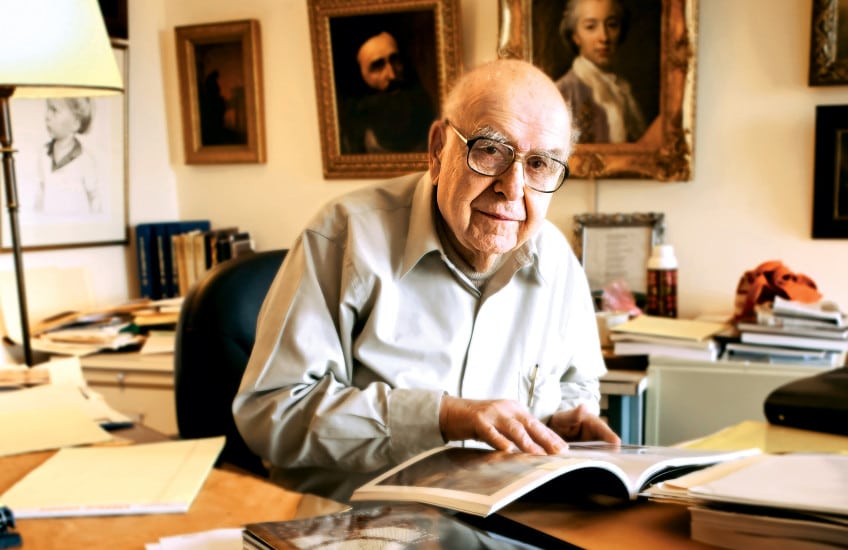

De Witt, the first Bader Curator and the steward of the collection between 2001 and 2014, sought to present the paintings of The Bader Collection, the majority of which were created more than three hundred years ago, as a collection of images wholly approachable to today’s audiences. His long and deep relationship with Bader meant that he worked closely with him to grow the collection in impactful directions:

“It took persistence and persuasion to convince Alfred Bader to acquire Willem Drost’s Self-Portrait as John the Evangelist, for example, for his collection. Even though he recognized its gravitas and grace, and he saw how important this historicized self-portrait by a student of Rembrandt’s was for his Rembrandt-oriented collection, he simply did not see himself as someone who collected expensive paintings. I believe he was pulled over the line by the vision of what this captivating work could give to others, to Isabel, who admired it, and to the people of Queen’s University. Accessibility and sharing were major drivers of his collecting activities, which I recognized and embraced. So too was an accessible art: scenes of scripture, mythology or history played by flesh-and-blood figures, not idealized or polished. He sought out everyday life scenes, instead of periwigged portrait sitters displaying wealth and status. With Rembrandt, and paintings such as his , with its burning emotion, or Portrait of a Man with Arms Akimbo, with its insistent resolve, our twenty-first century experiences met those of the seventeenth, as they did over Jacobus Vrel’s Woman Darning Socks, or the enigmatic Monogrammist I.S.’s Old Woman Singing. Constantijn Verhout shows the wealthy brewer Dirck Graswinckel sitting on a stool, looking into a beer jug, a scene of remarkable unpretentiousness. These works are all incredibly well painted, coming from a tradition of excellence already hundreds of years old by then. But I am equally entranced by their reverent observation of life, nature, and humanity in its everyday guise, and I endeavored to bring that message of shared experience across the centuries to Agnes’s audiences. Wrought Emotions: European Paintings from the Permanent Collection (2005-2007) did just that.

In its earlier years at Queen’s, the collection suffered criticism for its roughness and inelegance. But it is, in fact, these works’ directness and brilliance that will ensure they keep on giving.”34Personal communication with the author, 11 September 2022.

Coutré was the second caretaker of The Bader Collection, filling that role between 2015 and 2019. While there, she sought to integrate the collection more deeply into the broader life of the university by organizing exhibitions in tandem with programs that highlighted the interdisciplinary dialogues within the collection:

“The multidisciplinary potential of art of the Dutch Republic in the seventeenth century—because of its situation as a place of religious and social tolerance, its position as the birthplace of a new and mercantile-driven art market, its importance as the site where new genres of painting were established and flourished—has long compelled me. The art is, of course, beautiful, powerful, and complex, and there are many exhibition narratives that lend themselves to this collection. In my curatorial activities, I strived to develop exhibition narratives that reach beyond the art historical, which is particularly germane for a collection housed on a university campus. When formulating the premise for Rome, Capital of Painting in 2019, for example, I was keen to take a broad European look at the importance of the Eternal City for the production of art in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, but I also wanted to highlight notions of migration, knowledge exchange, and, in organizing the Isabel and Alfred Bader Lecture in European Art with Prof Dr Sybille Ebert-Schifferer, explore systems of professional connection and stylistic competition. The lecture focused on the ArsRoma database, which brings together art and computer science to ask new questions about ‘the formation of style and the reception of models, the motivation of patrons and the art market, the emergence of social and political networks of artists and their patrons—each of which encompasses data volumes that are too large and too complex to be processed by traditional research media.’35Sybille Ebert-Schifferer and Eva Bracchi, “ArsRoma—Art historical research database of painting in Rome 1580–1630,” Bibliotheca Hertziana [accessed 5 September 2022]. Similarly, with The Powers of Women: Female Fortitude in European Art, I sought to expand the repertoire of imagery related to the show by having a book-club event in which a faculty member in English led a discussion of Oscar Wilde’s Salomé in the exhibition. As Salomé was a subject absent from The Bader Collection, the discussion of Wilde’s play added a new dimension to the consideration of female strength presented in the paintings and prints on the walls.

I think all curators want to establish dynamic connections between audiences and works of art. Expanding the network of ideas proposed by an exhibition, beyond the art mounted on the wall, was a major priority during my time at Agnes.”36Jacquelyn N. Coutré, unpublished typescript, 1 May 2023.

The current custodian of The Bader Collection, Van de Meerendonk, has sought to position it within the art centre’s collections and the larger exhibition ecosystem as a hospitable and welcoming presence. Since her arrival in 2020, she has aimed to bring the collection into a larger dialogue of care and self-care:

“The strength of the collection in the area of seventeenth-century Dutch art—and above all, the quality of the works—allows for an illumination of European early modern art and culture that has the potential to be simultaneously rigorous, thoughtful and mesmerizing. The continuous re-examination of the collection through exhibitions and programs brings seemingly endless opportunities to show it in new and unexpected ways. My curatorial approach to The Bader Collection is generally rooted in an ethos and social practice of care, not only as this relates to the artworks but also the contemporary audiences that stand in relation to them. I ask myself, how can exhibition projects and other engagements with the collection better connect with the lived experiences of visitors? How might contemporary artists be inspired by historic art or invigorate their practice from such encounters? How might artistic projects and relationships grow from this collection and our interactions with it?

When proceeding from such motivations, it is crucial to display and enact a certain sensitivity to the diversity that is inherent to relationality. Scholarly and academic audiences will generally have a very different investment in the art and cultural history of early modern Europe than the general public, and the presence of myriad positionalities within both worlds means that a wide spectrum of inquiries will be brought to the works at any given time. The situation of Agnes and Queen’s University on Haudenosaunee and Anishinabek lands further mandates accountability and transparency regarding the entangled histories of Dutch colonial trade and settlement, including in North America, and the ongoing suppression of Indigenous cultures that resulted from them. Whether by foregrounding the impact of an increasingly colonial material culture on seventeenth-century Dutch painting, as was the main aim of the exhibition The Fabrics of Representation (2022), or by questioning the historic privilege inherent to private space in Studies in Solitude: The Art of Depicting Seclusion (2021-2022), the celebration of these exceptional artworks is contingent on an acknowledgement of the asymmetrical power relations that shaped them.”37Personal communication with the author, 16 September 2022.

With courage and ingenuity, the Bader Curator of European Art has had the exhilarating charge to continuously “re-vision” the collection through exhibitions.38“Re-vision—the act of looking back, of seeing with fresh eyes, of entering an old text from a new critical direction…” As quoted in Maura Reilly, Curatorial Activism: Towards an Ethics of Curating (London: Thames and Hudson, 2018), 23.

This survey of exhibitions of historical European art has revealed that Baroque imagery remains ripe for broad interpretation in the twenty-first century. From innovative themes to novel manners of representation, the high-quality paintings in the collection address the constants of the human experience. Furthermore, the import of having a specialist in early modern art—specifically in Dutch painting—to interrogate the collection again and again expands the collection’s exhibition potential. Because of the hugely generous donations of Drs Alfred and Isabel Bader, the Bader Curator of European Art is sure to continue to discover new discourses within the collection, invigorating its objects with exciting new meanings for years to come.

Link to PDF.

Link to PDF.![<p><em>Massey Collection: Figures and Still Lifes</em> (Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada [1966]). Queen’s University Archives, Agnes Etherington Art Centre Fonds. <a href=](https://agnes.queensu.ca/site/uploads/2023/05/Fig-7_3740-2-16-Catalogue_Page_1-1440x1118.jpg) Link to PDF.

Link to PDF. Link to PDF.

Link to PDF. Link to PDF.

Link to PDF.