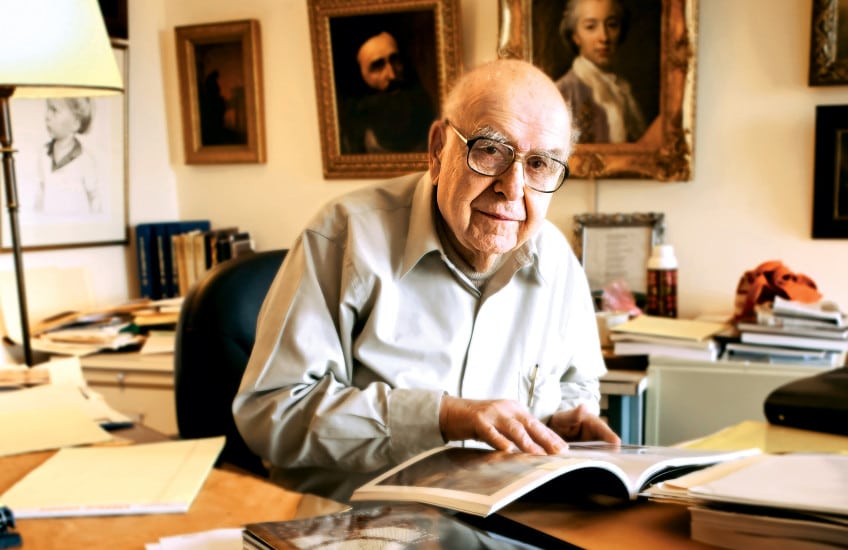

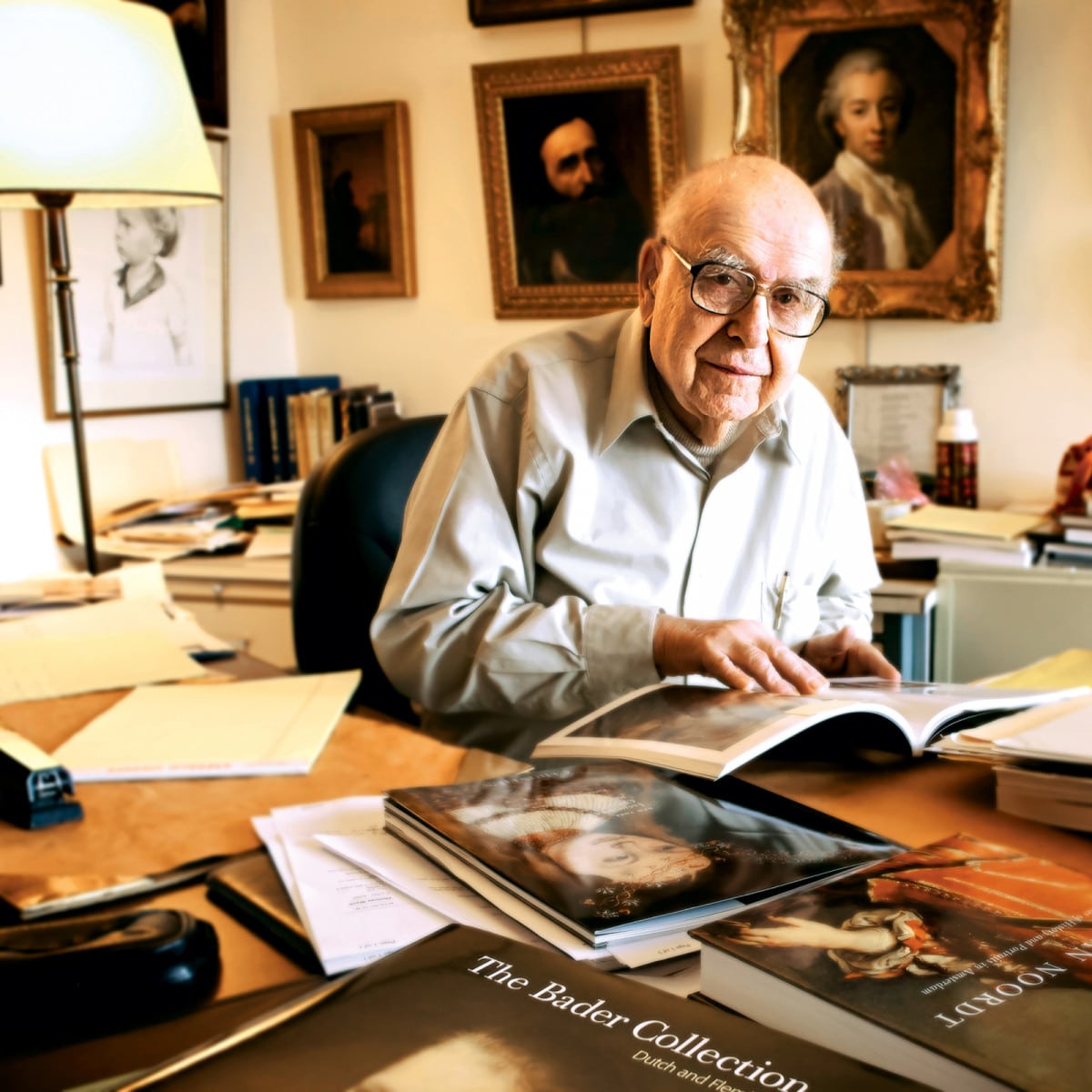

David de Witt, Senior Curator, Rembrandt House Museum

Alfred Bader and Rembrandt

It is not Rembrandt’s most famous painting, the David and Jonathan in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, and its authenticity has sometimes been doubted by scholars. But it showed up so often in the talks and lectures given by Alfred Bader that it may well have been his favorite painting. He vigorously defended Rembrandt’s authorship, and his judgement won out as the work was later reaffirmed as by the artist. He was especially drawn to the deep bond between the two biblical figures, evoked in the moment as they parted ways for good. A powerful human drama, and a poetic moment, undoubtedly of personal significance for someone who lost various family members in the Holocaust.

Human values, such as empathy, sincerity, and directness, drove Bader’s keen interest in and admiration for Rembrandt for over six decades, during which he followed some major twists and turns in scholarly research on the artist. The four paintings by Rembrandt’s hand now in the collection of the Agnes Etherington Art Centre are only part of the story.

The first encounter took place in the late 1940s, when Alfred Bader was at Harvard for a Ph.D. in chemistry. His professor gently kidded him for taking time out to attend open lectures on art history. His own inclination played a role, and he also a felt connection to the professor of those lectures, Jakob Rosenberg, a Jewish refugee like himself. His own father had been an art dealer, but died when Alfred was only three, and so did not pass any knowledge on to his son. Growing up in the turmoil of Depression-era Vienna, and in the years of being a refugee and then a student at Queen’s University, Bader experienced limited contact with the arts.

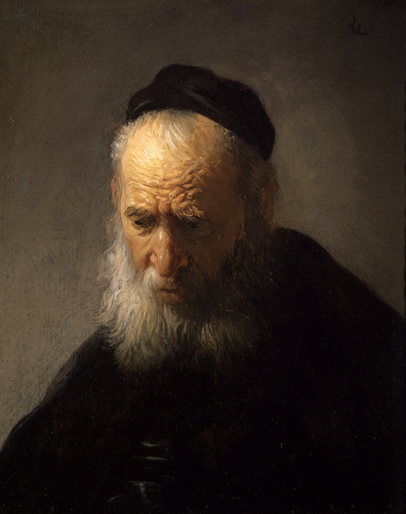

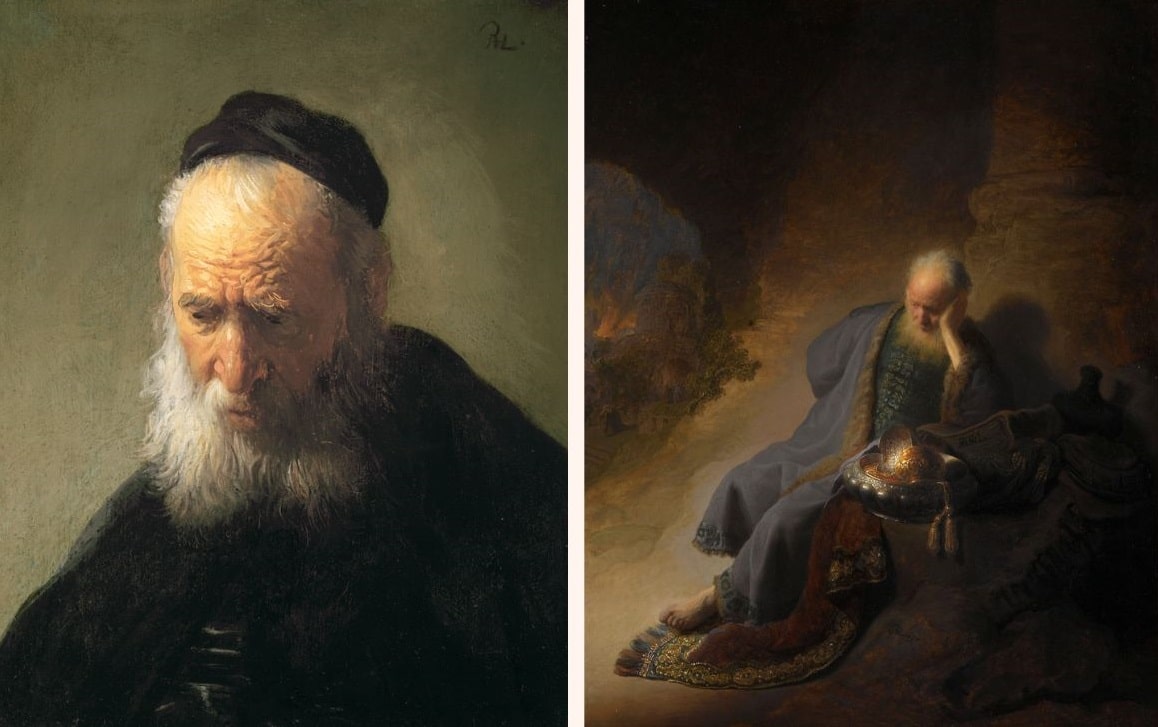

It so happened that the young Alfred Bader encountered Jakob Rosenberg at the very moment that Rosenberg’s interest was focused on Rembrandt. He had just published a monograph on Rembrandt in 1948, the impact of which would stretch out over decades, with new editions appearing in 1964 and 1980. His account of the artist was furthermore remarkable for emphasizing human connections, of Rembrandt with his family and neighbours in studies and portraits, and of Rembrandt’s deep meditation on the emotional states and situations of the figures in his narrative paintings. These values would form lifelong collecting priorities and criteria for Bader, as brilliantly illustrated in his first acquisition of an accepted Rembrandt in 1979, the early Head of an Old Man in a Cap.

Rembrandt was long thought to have represented his father in such works, his empathy drawing from a powerfully personal bond. The renowned art historian Julius Held went even further, pointing to the evidence that Rembrandt’s father went blind in his later years, and linking Rembrandt’s interest in the Book of Tobit to the blindness of Tobias’s father Tobit, identifying him with his own father, and himself with the young Tobias. Later, Bader would be open to the realization that Rembrandt’s father looked quite different, and that the young artist here selected a striking local model also deployed in other Biblical roles, such as that of the prophet Jeremiah. The gripping evocation of emotion arose from Rembrandt’s groundbreaking initiative to systematically scrutinize emotional expression, as recorded in various drawings, etchings, and painted tronies.

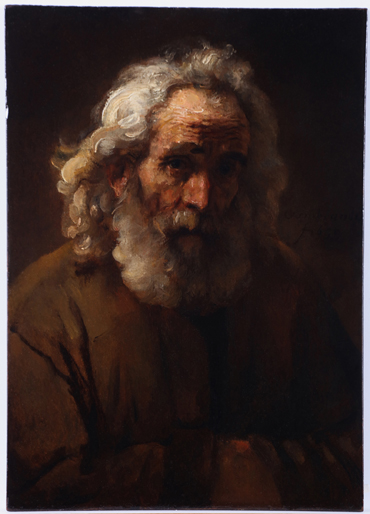

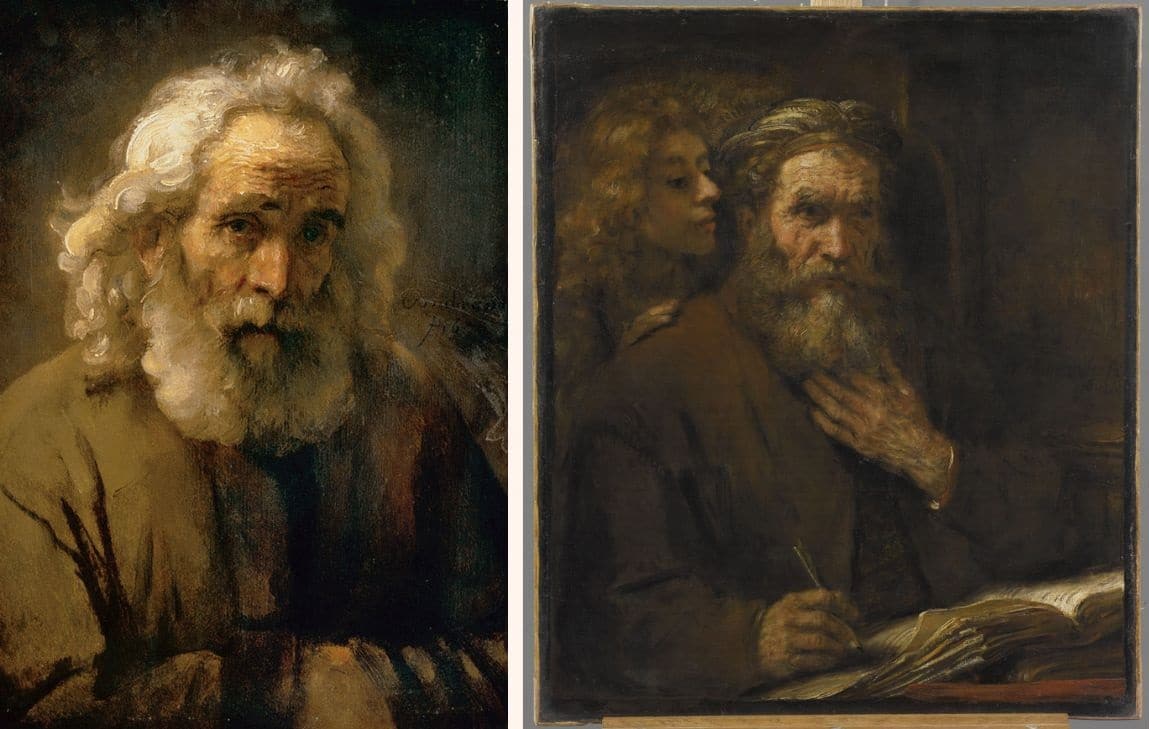

Human emotion also projects from the second Rembrandt painting that Bader was able to acquire for his collection, the Head of a Man with Curly Hair of 1659. It is seen as a study of the lighting Rembrandt would use for his St. Matthew in the Louvre, but as it is signed and dated, Rembrandt clearly presented this work as a finished work as well, demonstrating the artistic challenge of lighting as well as emotion. Such character heads, or tronies, were generally aimed at connoisseurs of art, who may not have necessarily been affluent, but were enthusiastic and well-informed, and close to the master’s heart. It was reported of Rembrandt that in his later years he associated mainly with artists and those connected to art. In a sense, Alfred joined this company over three centuries later.

Left: Rembrandt van Rijn, Head of an Old Man in a Cap, around 1630, oil on panel. Gift of Alfred and Isabel Bader, 2003 (46-031). Right: Rembrandt van Rijn, Jeremiah Lamenting the Destruction of Jerusalem, 1630, oil on panel. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Left: Rembrandt van Rijn, Head of an Old Man with Curly Hair, 1659, oil on panel. Gift of Linda and Daniel Bader, 2019 (62-002). Right: Rembrandt van Rijn, St. Matthew and the Angel, 1661, oil on canvas. Musée du Louvre, Paris. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY. Photo: Herve Lewandowski

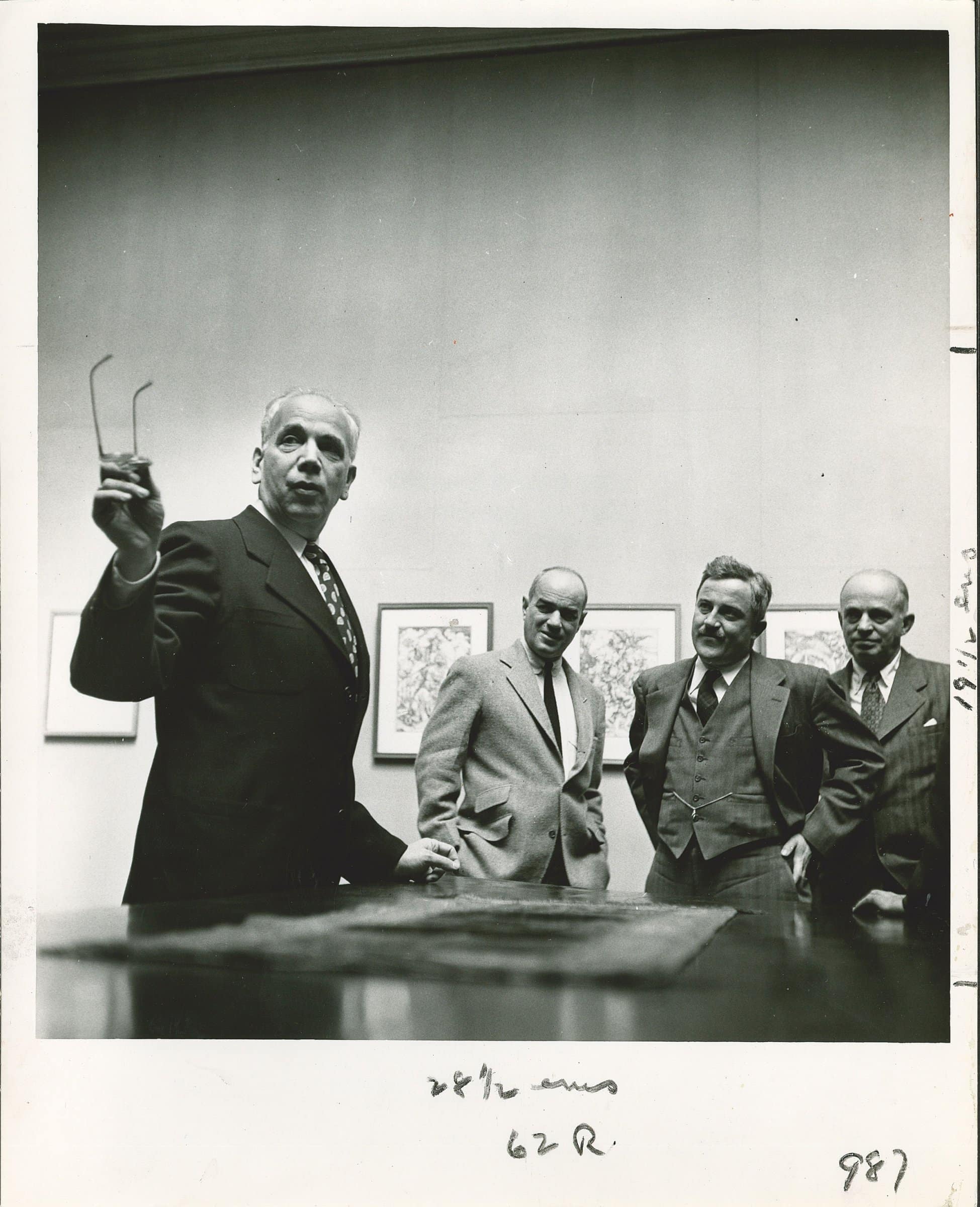

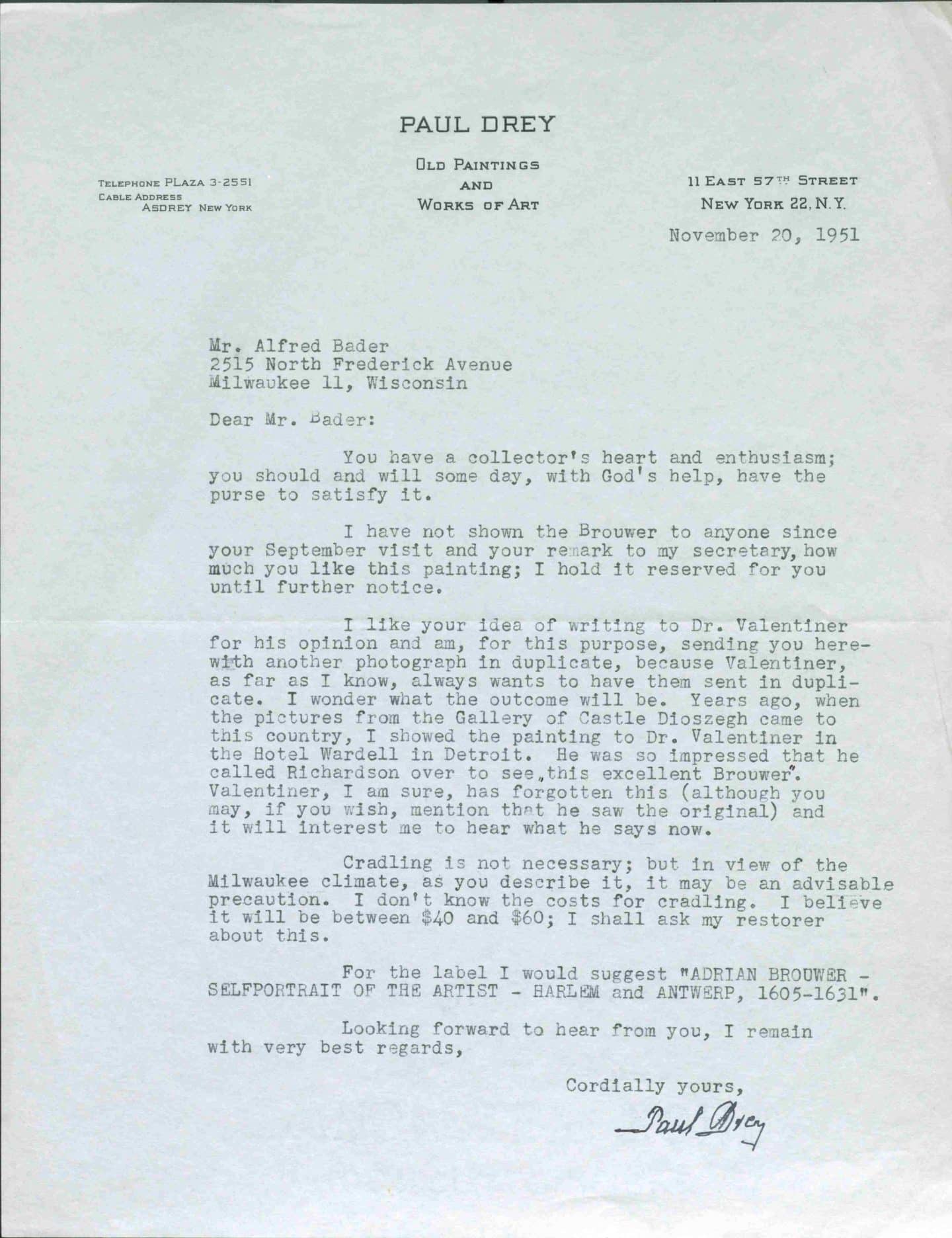

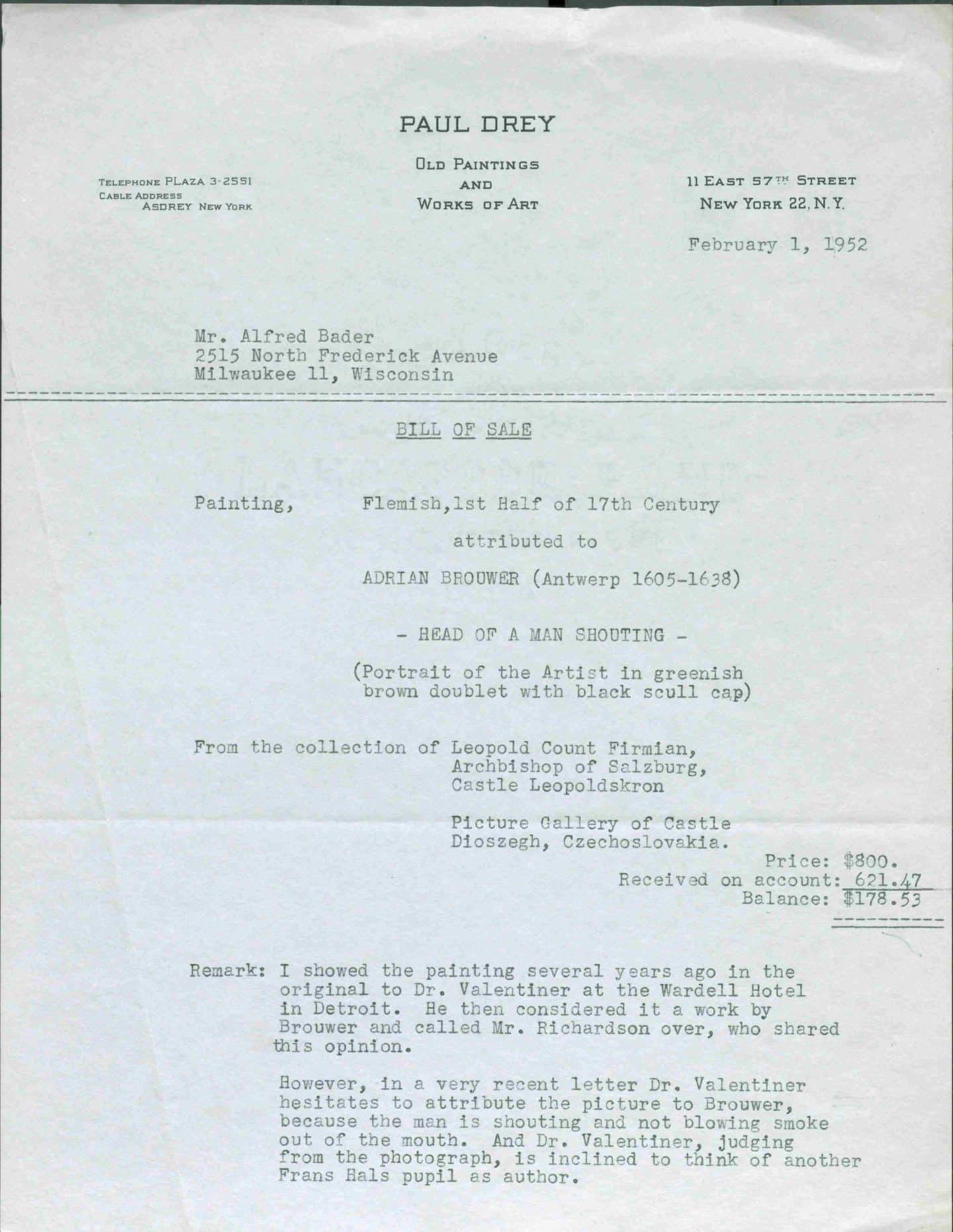

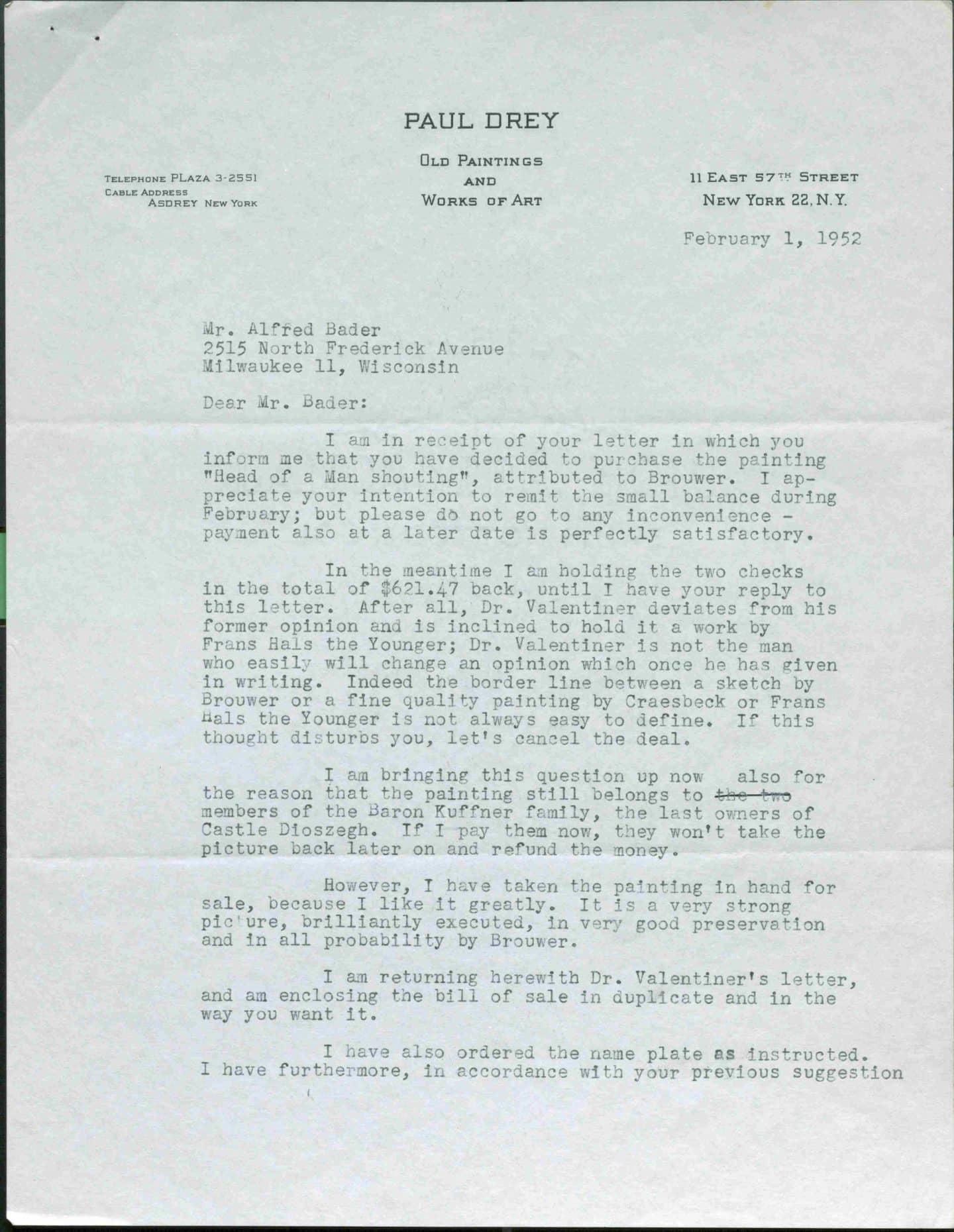

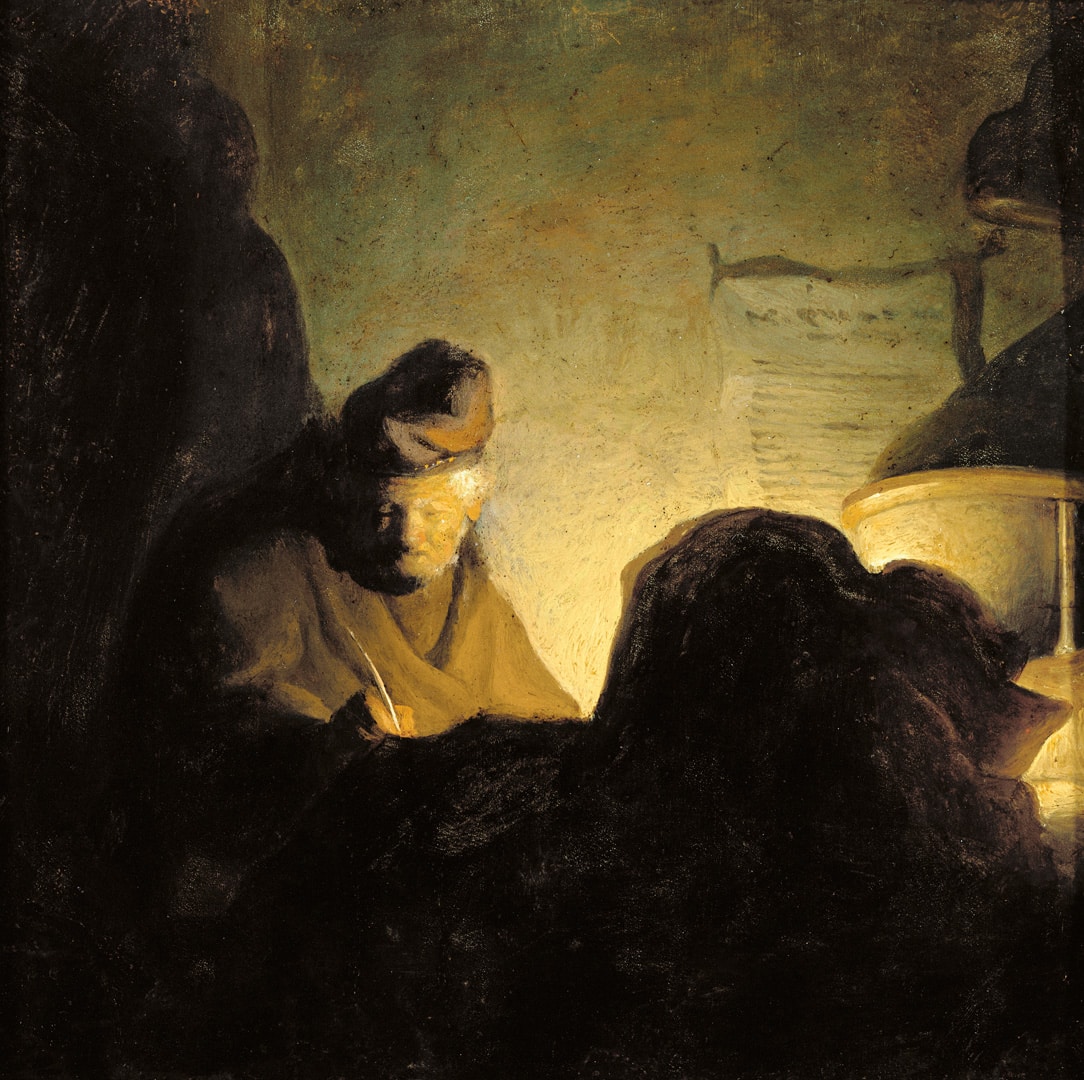

The first encounters took place in a lecture hall. And not much later, still a poor grad student, Bader was prompted to buy his first Old Master painting on installments. Eight years later, as an entrepreneur enjoying success, he returned to Harvard with his first painting attributed to the master, a small Scholar by Candlelight on copper, to seek Rosenberg’s opinion.

Letters from art dealer Paul Drey to Alfred Bader, 1951-1952. Queen’s University Archives, Alfred Bader Fonds.

Letters from art dealer Paul Drey to Alfred Bader, 1951-1952. Queen’s University Archives, Alfred Bader Fonds.

Letters from art dealer Paul Drey to Alfred Bader (page 1), 1951-1952. Queen’s University Archives, Alfred Bader Fonds.

Letters from art dealer Paul Drey to Alfred Bader (page 2), 1951-1952. Queen’s University Archives, Alfred Bader Fonds.

Joos van Craesbeeck, A Man Surprised (Adriaen Brouwer?), around 1635, oil on panel. Milwaukee, Estate of Isabel Bader

Attributed to Rembrandt van Rijn, A Scholar by Candlelight, 1628–1629, oil on copper. Gift of Isabel Bader, 2019 (62-004.02)

Over the years, he would correspond with over seventy different art historians. This seems astonishing, but makes sense when paralleled to his work at Aldrich Chemical Company. He regularly visited and consulted with chemists in their labs, establishing relationships with them. It is clear that he prioritized interpersonal communication, both in work and research.

While it seems surprising to us today, looking at a collection that is so focused on Rembrandt, Bader spent much of the 1960s collecting widely in the areas of Northern and Southern Baroque.

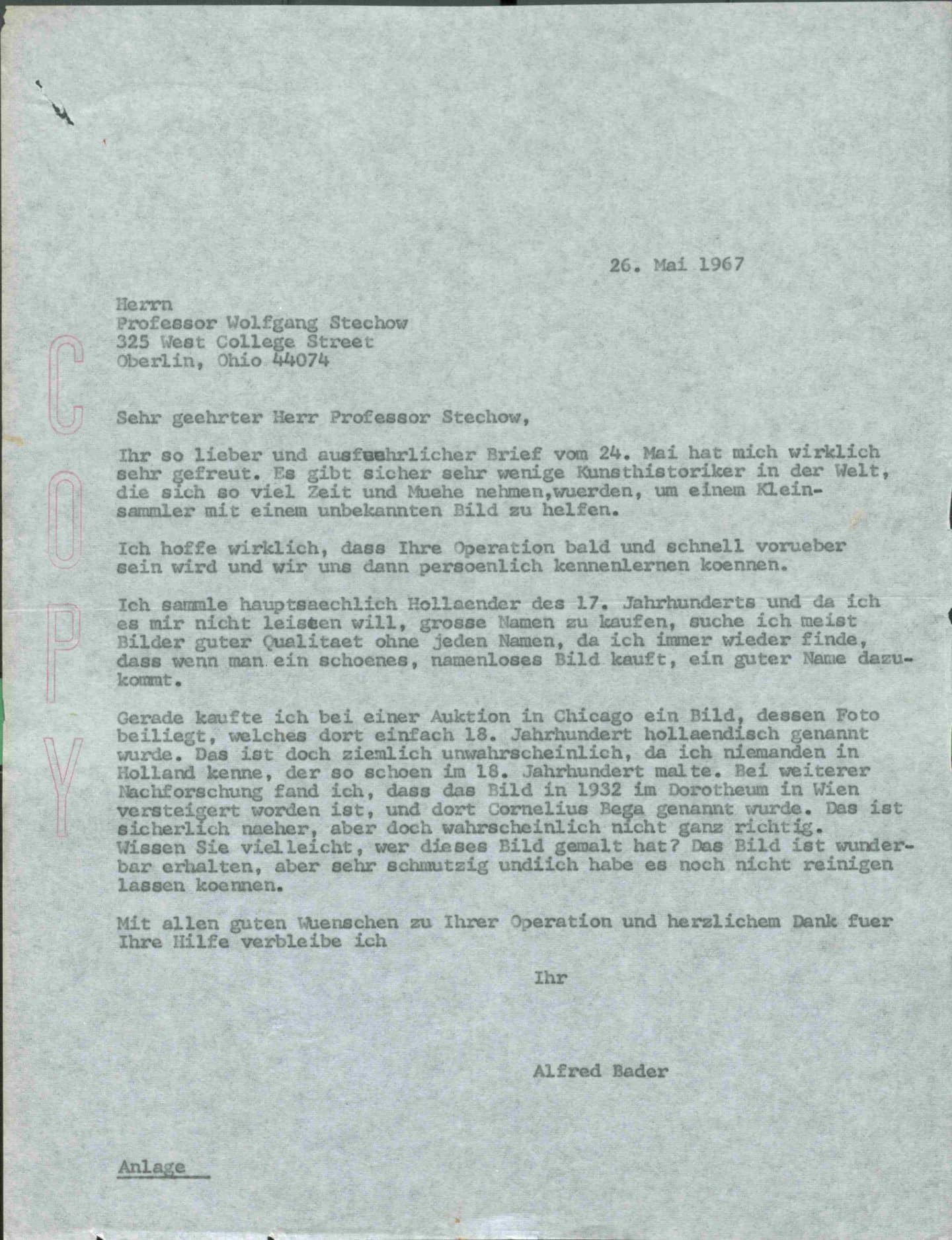

He valued the empathic expression of emotional experience, against the prevailing taste for more idealizing art, and this required zeal and vision. He found kindred spirits, such as the Chicago opera tenor Harry Moore, whom he would regularly visit to discuss, and trade, paintings. And also Wolfgang Stechow, an art history professor at Oberlin, with a broad interest in Northern Baroque art.

Andrea Lanzani, The Blind Belisarius, around 1695, oil on canvas. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Alfred Bader, 1971 (14-006)

Lodovico Cigoli, The Vision of Saint Francis, around 1599, oil on canvas. Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Alfred Bader, 1976 (19-078)

By 1971, a focus had developed. He drew closer to Rembrandt on account of his well-known devotion to Biblical themes in his art, specifically the Old Testament, the Jewish Bible. In that year Bader published a short scholarly article in The Burlington Magazine on a painting under Rembrandt’s name in the Hermitage, proposing an alternative interpretation, instead of Haman Recognizes His Fate.

He even entered into scholarly debate on a painting by Rembrandt’s friend and follower, Gerbrand van den Eeckhout.1Alfred Bader, “A new interpretation of Rembrandt’s ‘Disgrace of Haman,’” Burlington Magazine 113 (1971): 473; and (with Sam Nystad), “On the Evaluation of Evidence in Art History,” Burlington Magazine 114 (1972): 795; other articles include: “Aert de Gelder’s Forecourt of a Temple,” Burlington Magazine , 112 (1970): 691; and “An unknown self-portrait of Michael Sweerts,” Burlington Magazine 114 (1972), p. 475. This was around the time that scholars such as Christian Tümpel charged onto the stage with new insights into Rembrandt’s sources for themes, primarily in older prints. Correspondence between the two was soon established and continued until Tümpel’s untimely passing in 2009. In 1986, a younger iconographic specialist, Volker Manuth, visited from Berlin, the start of another long friendship. Between 1995 and 2002, Manuth served as the first Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art in the Department of Art at Queen’s.

Volker Manuth looking at Jacob van Spreeuwen, Allegory of Vanitas, with Queen’s students in Agnes’s vault, around 1996. The author, David de Witt, is the second student from the right.

There was a longstanding notion that Rembrandt cultivated a special sympathy for Jews.2Michael Zell, “Eduard Koloff and the historiographic Romance of Rembrandt and the Jews,” Simiolus 28 (2001): 181–197. This derived in part from his treatment of many Old Testament themes, but even more so from the rendering of various figures in these works as Jews, with features likely drawn from models living nearby in Rembrandt’s own neighbourhood, which was transforming into a Jewish quarter with arrivals of Sephardim from Spain and Portugal, and Ashkenazim from Germany and Poland. Such figures, studied from life, also appear in studies and single figure paintings, complete with Eastern European costume details such as tall fur hats. Generally, they are rendered as individual subjects, rather than as stereotypical types. This, for obvious reasons, appealed to the young Jewish refugee fleeing Nazi controlled Vienna, as it had to scholars like Held and Rosenberg.

More recently this relationship has been questioned, citing evidence of several conflicts that Rembrandt had with Jews.3Gary Schwartz, “Rembrandt’s Hebrews,” Wissenschaft auf der Suche. Beiträge des Internationalen Symposiums Berlin — 4. und 5. November 2006, Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen 51 (2009): 33-38. A dispute over the likeness of a portrait in 16544Adriaen Lock notarizing Diego d’Andrada’s complaint regarding a true likeness, 23 February 1654, RemDoc. Radboud University Nijmegen, Nijmegen, Netherlands. http://remdoc.huygens.knaw.nl/#/document/remdoc/e1661. is however a close echo of one in 1639 of the powerful (and not at all Jewish) Andries de Graeff, later burgomaster of Amsterdam, in which Rembrandt also stood his ground.5Nicolaes Listingh notarizing a deposition by Hendrick van Uylenburch concerning a portrait of Andries de Graeff, 1659, RemDoc. Radboud University Nijmegen, Nijmegen, Netherlands. http://remdoc.huygens.knaw.nl/#/document/remdoc/e12837. In a similar vein, his dispute concerning costs of construction work on a shared wall would have arisen regardless of the neighbour’s background, as Rembrandt had run out of money.6Benedict Baddel notarizing a deposition about the renovation (“timbering up”) of Rembrandt’s and his neighbour’s house, 9 February 1654, RemDoc. Radboud University Nijmegen, Nijmegen, Netherlands. http://remdoc.huygens.knaw.nl/#/document/remdoc/e4647; http://remdoc.huygens.knaw.nl/#/document/remdoc/e4640. And when a more distant friend penned a poem meant to be added below the Hundred Guilder Print, with anti-Jewish aspersions, Rembrandt did not print it. Recent evidence has confirmed his repeated contact with the renowned Rabbinic scholar Menasseh ben Israel.7Steven Nadler and Victor Tiribás, “Rembrandt’s Etchings for Menasseh ben Israel’s Piedra Gloriosa: A Mystery Solved?,” Kroniek van het Rembrandthuis (2021): 1-17, https://doi.org/10.48296/KvhR2021.01. Rembrandt’s attitude toward Jews was probably not more than a product of his intellectual openness and enquiry. He likely had contact with Jewish neighbours, much like he maintained contacts with Mennonites, Catholics, and even a pupil who was decidedly libertine and familiar with the radical political thinker Franciscus van den Enden, who was a tutor of Spinoza. His religious paintings reflect a clearly Christian standpoint, unsurprisingly, but it remains interesting in this respect that he did not formally join the Reformed Church.

There are further indicators of this open attitude. Often cited is his Kunstcaemer, or Cabinet of Curiosities, which included objects like shells, armour, and stuffed animals from distant regions, in addition to artist’s paraphernalia such as casts of feet and hands. But it also emerges in his comprehensive range of subject matter, from history to still life. Deeply entwined with this attitude is his pursuit of an art based on study from life, as it was, without selection or idealization. It can fairly be characterized as the single driving artistic principle that Rembrandt observed through the various developments in his art. Rembrandt’s unwillingness to flatter the rich and powerful of his day cost him the considerable social capital that his artistic talent would otherwise have guaranteed, a lament repeated by various writers of the period. Rembrandt’s reputation suffered considerably from criticism of his realism, which was linked directly to his conviction that art should follow life, as reported by his biographers in connection with his unidealized male and female nude studies. His pupil Maes was presented as an example of a shrewd artist who abandoned realism in portraiture in order to deliver the idealizing flattery that clients desired. Clients unlike Alfred Bader. There is no such example by Maes in The Bader Collection, however there are two pieces of his earlier, grittier work when he still followed Rembrandt.

Much of the power of the Head of an Old Man in a Cap derives from Rembrandt’s intensive study of the aged features and the agonized expression from life, of which he made various drawings and even several demonstrative prints. Rembrandt continued to develop ways of evoking life more convincingly throughout his career, including ways of suggesting the liveliness of living beings, and the suggestion of their thoughts and emotions, even fleeting states of mind. The open brushwork of his late style, for instance, served to suggest an emotional state, including dynamic verve, as seen in the brilliant Portrait of a Man with Arms Akimbo, the last Rembrandt that Bader acquired. The widened range of brushstrokes also brought greater emphasis to the effect of three-dimensional form and space, with bold and forceful impasto strokes visually drawing close to us, and setting out surface direction, against smooth and thin paint application. In general these touches lend the work as a whole a bolder and more vivid presence.

Rembrandt’s achievements in art did continue to draw some appreciation through the 1700s, but it would only be in the second half of the nineteenth century that they came to be fully appreciated again, even more than in his own heyday in the 1630s. Social and political developments in the wake of the French Revolution reversed the negative assessment of his attention to common types and everyday life. Alfred Bader concurred with more than the usual conviction, however, in favouring depictions of old men, often bald and wrinkled, in sombre contemplation. This unusual preference merits explanation, which he regularly offered in public talks on art, art history, and collecting. Much more so than scholarly periodicals, the lecture podium served as the main outlet for Bader’s research and reflections on art, and Rembrandt was a favored topic. There he would discuss his admiration for and acquisition of astonishingly gritty paintings such as the rendering of Mary Magdalene by Rembrandt’s friend and associate, Jan Lievens.

His acquisition of two paintings by the obscure Fleming Jan van de Venne, with brownish palette and rough, stony faces, was entirely in this vein. It was only later that he yielded to the entreaties of Isabel (who regularly protested, “Not another old man!”), and brought works such as the Self-Portrait as St. John the Evangelist by Rembrandt’s brilliant pupil, Willem Drost, into the collection.

Although he had not studied art history formally since the lectures at Harvard, Alfred Bader devoured scholarly publications on Rembrandt and other artists and steadily cultivated the approach of a researcher in this area. Tracing his correspondence, it appears that a turn took place in the late 1960s. The spirit of active enquiry was summoned by impressive and intriguing works acquired under the name of Rembrandt, complete with signatures sometimes, which turned out to be by pupils or followers. One significant moment was the cleaning of the Quill Cutter, in which Rembrandt’s signature disappeared (as it was added later and still soluble), only to reveal a signature by the nearly-unknown follower Paulus Lesire.

In his correspondence, and in his public lectures, Bader drew attention to the considerable achievement of the artists around Rembrandt. He began to correspond with the Stuttgart professor Werner Sumowski, who had embarked on an ambitious project to organize and attribute thousands of such works around the world, largely on the basis of photographs. One artist who particularly fixed his attention was Jan Lievens, who was long seen as a weak imitator of Rembrandt. He came to be recognized as a major artist in his own right who likely taught Rembrandt at first, and later cultivated a friendly artistic competition with him, producing many works comparable in quality. Finally, a major exhibition in 2008-2009 cemented Lievens’s reputation, and included four Bader paintings.

Transcript

- Name Text

The biggest development in Rembrandt studies in the late 1960s was a drive to purge the oeuvre of falsely attributed Rembrandts, for which the Rembrandt Research Project was established in 1969 in Amsterdam during the 300th jubilee of his death. The project would regularly draw wide media attention with one rejection after another of works long known as by Rembrandt. Bader would follow its work avidly for the rest of his collecting life, occasionally taking issue with its decisions.

The Rembrandt Research Project also championed the examination of paintings by various technical methods, mainly X-ray, dendrochronology of wood panels, thread counting of canvas supports, pigment analysis and cross sections, infrared reflectography, and analysis of the composition of grounds. As a scientific researcher with decades of experience, Bader was equipped to follow these developments, and noted with others that these results were sometimes discarded in favour of traditional stylistic assessment. Even then he was able to earn his moment in the sun, when Head of an Old Man in a Cap was rehabilitated as a Rembrandt. He had purchased the work at auction as a rejected Rembrandt, on the conviction that this was incorrect.8Alfred Bader, Adventures of a Chemist Collector (London Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1995), 216. He perceived that the “rough style” of the painting, which had lead to its rejection by the project, was still Rembrandt working in another stylistic mode. He was vindicated in 1996 when the project, now led by Ernst van de Wetering, accepted it, armed with new technical evidence: the watermarks in a reproductive print after the painting.9Erik Hinterding et al., Rembrandt & Van Vliet. A Collaboration on Copper (exh. cat. Amsterdam: The Rembrandt House Museum, 1996): 60, note 2.The pendulum could swing the other way too, as when X-rays proved that the Louvre version of Venus and Cupid (Hendrickje Stoffels and Cornelia van Rijn) was the original and the Bader version a pupil’s copy (perhaps by Godfrey Kneller).10Ernst van de Wetering, Rembrandt’s Paintings revisited. A complete survey (Dordrecht: Springer, 2017): 636-638.

Unknown artist, after Rembrandt van Rijn, Venus and Cupid, after 1660, oil on canvas. Paris, Musée du Louvre.

Unknown artist, after Rembrandt van Rijn, Venus and Cupid, around 1661, oil on canvas. Milwaukee, Estate of Isabel Bader.

The meaning of Rembrandt keeps expanding, as ongoing enquiry and research have yielded a larger figure than the romantic isolated genius of the past, even while this research has “shrunk” his oeuvre. Alfred Bader contributed to this development with his relentless and vigorous promotion of the significance of the school, casting Rembrandt’s pupils, followers and friends not as weak imitators, but as talented and driven artists who consciously supported and further developed the artistic initiatives Rembrandt had set out. Bader’s own study and correspondence with scholars fed his collecting and his philanthropy, supporting scholarship in the museum as well as in academia. As a leader of a large organization that combined research and production, he perceived a team around Rembrandt then and envisioned another team supporting this scholarship today.

Agnes uses cookies to provide the best possible online experience. Learn more about our privacy practices.