The presence of Alfred Bader is felt deeply at Agnes. Reminders of his larger-than-life vision and generosity abound—from the many artworks donated, exhibition and study spaces funded, to the many people whose lives he, along with his wife Isabel, his first wife Helen (Danny) and their sons Daniel and David, changed in immeasurable ways. This connection is perhaps felt even more strongly by the Bader Curator of European Art, who works intensely with The Bader Collection and is charged with its stewardship, a position I have been privileged to hold since 2020.

While I was fortunate enough to get to know Isabel before her passing in August 2022, my Bader curatorship was the first to commence after Alfred’s passing in December 2018. Despite this, his interests and vision inform many decisions around the collection and its associated programs. Due to the wealth of material left—Bader’s two autobiographies, his writings on painting in Sigma-Aldrich’s Aldrichimica Acta, his personal papers preserved at Queen’s Archives, and of course, the more than 500 artworks now in our care—a robust impression of the collector’s idiosyncrasies and priorities is allowed to take shape. Writing this essay, I can imagine a lack of pretension with which he might advise me not to spend so much time writing about him rather than the artworks he so loved. Therefore, to this Alfred Bader—an enduring creative and intellectual interlocutor within Agnes’s conversations—I propose, as a compromise, to write about his personal and philanthropic legacy carried forward in the collection, and how it finds connection with the ideals guiding the vision for the museum’s future.

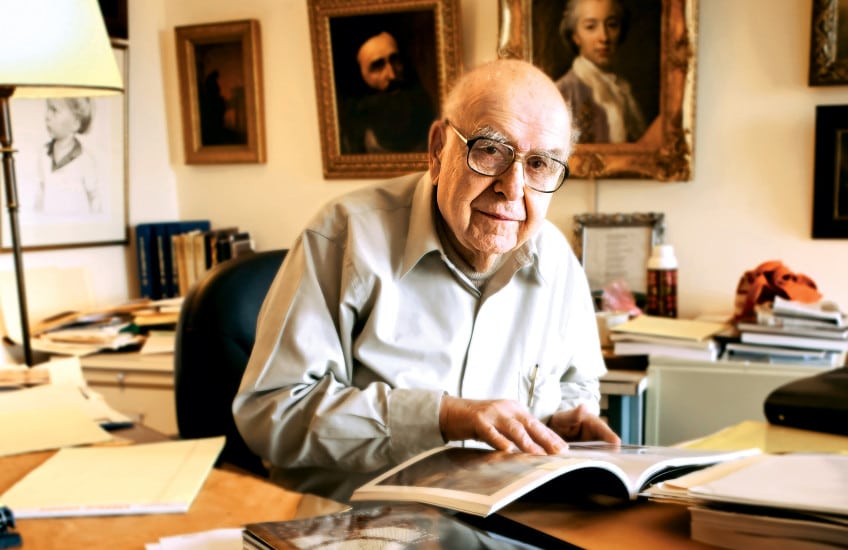

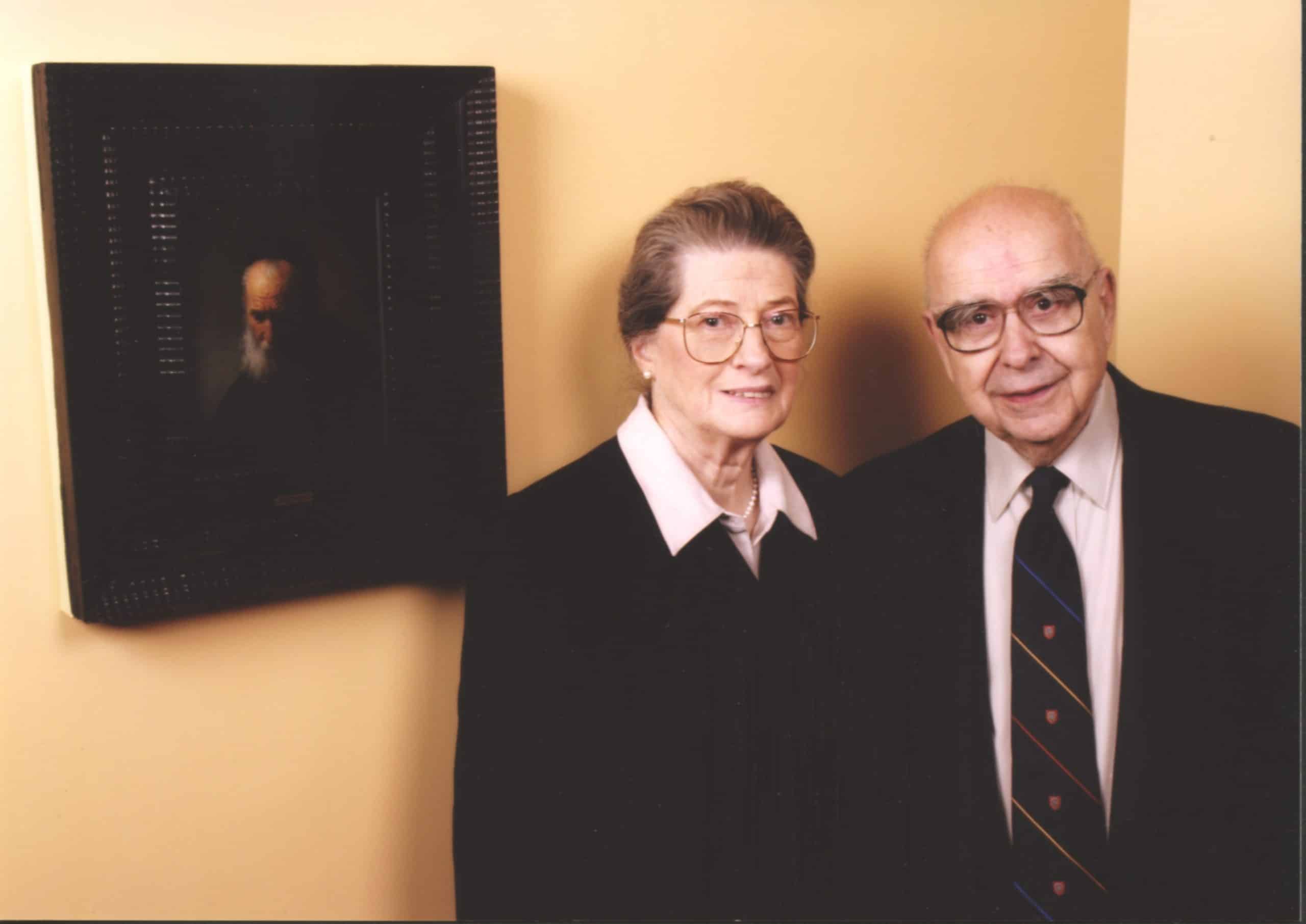

Drs Alfred and Isabel Bader with Rembrandt van Rijn’s Head of an Old Man in a Cap, 2003.

Agnes Etherington Art Centre’s expansion under construction in 1999, funded in part by a generous gift from Alfred Bader.

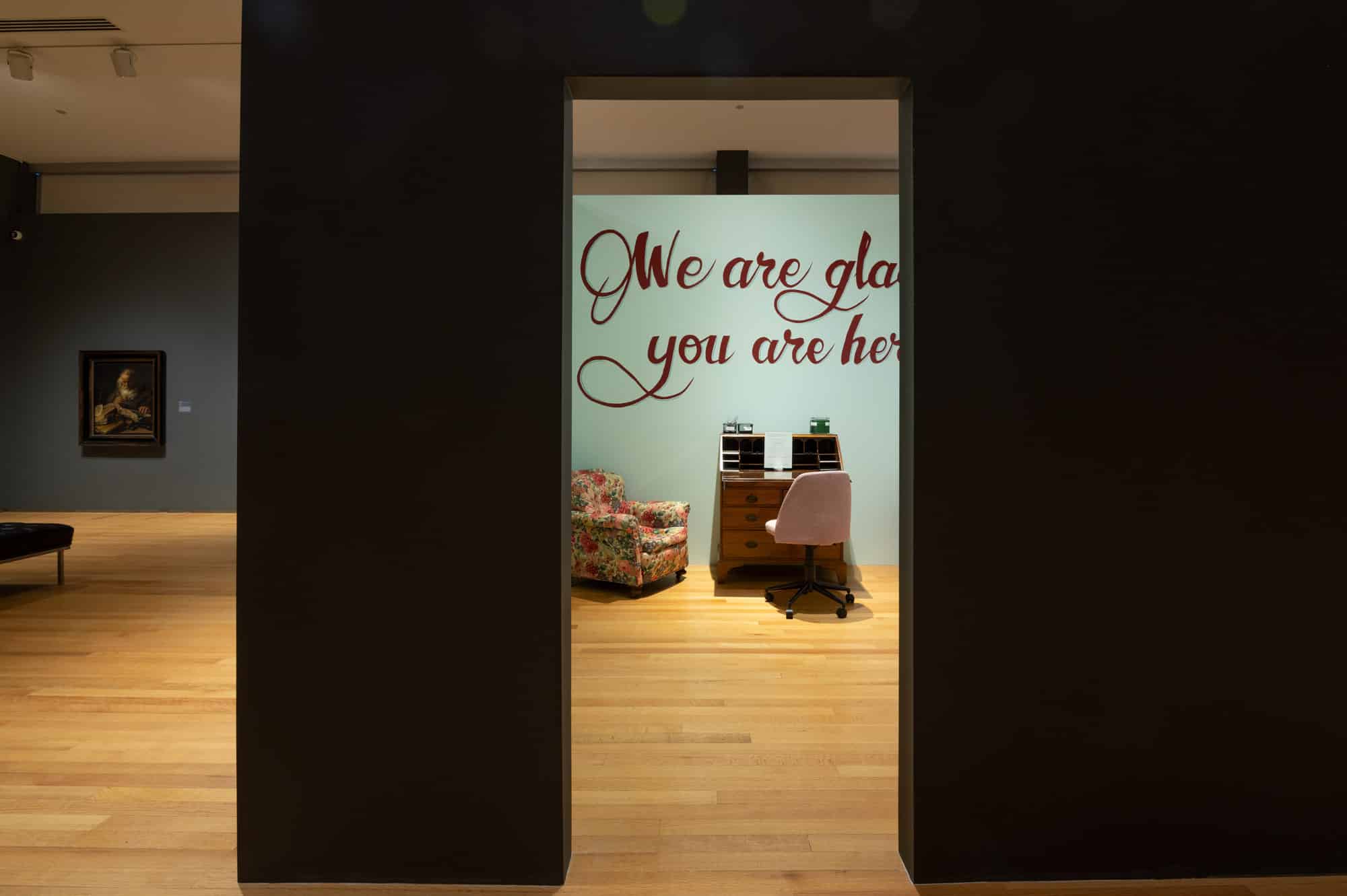

In that near future, Agnes is poised to reopen under the header of Agnes Reimagined, which, as Agnes Director and Curator Emelie Chhangur describes, “is a long-term social practice project, with architecture as its medium and the curatorial as its methodology … a proposition from which new museological practices emerge.”1 Within this methodological framework, we will be required to rethink not only how The Bader Collection finds its place in a different spatial context, but also how it can best fulfill this shared vision. How can the collection enter a new chapter of engagement while building on the strong foundation of scholarship, renown, and appreciation it has accumulated over time? One answer lies in the values with which it was formed.

Any collection is inevitably shaped by a collector’s preferences and interests, not in the least those pertaining to artistic and aesthetic considerations. Yet a more subdued quality of private collections—formed, after all, through the deeply personal process of selecting, curating and enjoying artworks during one’s lifetime—lies in the personal ethos of the collector. This seems particularly true for The Bader Collection, which in myriad ways reflects Bader’s ideals and sensibilities.2 For more elaborate discussion of the correspondences between these values and Alfred Bader’s collecting activities, see Suzanne van de Meerendonk, “Drawn From Life: Alfred Bader’s Collecting Interests in Context” in Tanya Paul, Catherine Sawinski and Suzanne van de Meerendonk, Art, Life, Legacy: Northern European Paintings in the Collection of Alfred and Isabel Bader (Seattle: Marquand Books, 2023), 27-37. The link between Bader’s biography and collecting preferences was also explored in the exhibition Alfred Bader Collects: Celebrating Fifty Years of The Bader Collection, curated at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre by then Bader Curator of European Art Dr. Jacquelyn N. Coutré in 2017. The life of this “chemist-collector” was marked by both extraordinary successes as well as hardships at a young age. These formative experiences, which include a harrowing escape from Nazi-occupied Austria and subsequent internment in a prisoner-of-war camp in Southern Quebec, shaped a lifelong commitment to principles of generosity, hospitality and social justice. Bader’s own perseverance through these struggles, as well as the kindness of others shown during crucial moments, also inspired a deeply held belief in the power of individual agency and responsibility.3Yechiel Barchaim has described Alfred Bader’s role in his philanthropy by referencing the teaching of Hillel in the Talmudic Tractate, Pirke Avot (The Sayings of the Fathers II:6), “In a place where there are no men, strive to be a man” explaining this could be interpreted either as “one should be virtuous even in the absence of any partners or observers” or “where no one else will step forward, you do it.” Alfred Bader, Chemistry & Art: Further Adventures of a Chemist Collector (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2008), 224-225; On the topic of Abraham and the destruction of Sodom, Bader expressed a similar opinion by citing the quote attributed to President John F. Kennedy “One man can make the difference, and every man should try.” Aldrichimica Acta 6, no. 1 (1973).

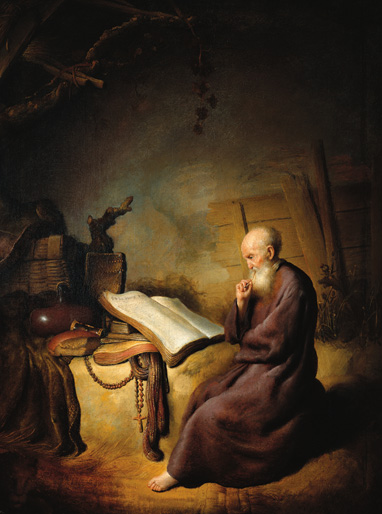

Not surprisingly, such themes frequently surface in The Bader Collection, particularly in biblical works with strong moral implications such as Elijah and The Widow of Zarephath, Ruth and Naomi and The Good Samaritan.4For a more examples, see Van de Meerendonk, “Drawn From Life.”